Guy Warren: a guy who has made his mark

Review sits down with Australia’s oldest living practising artist, Archibald Prize-winning painter Guy Warren.

Guy Warren opens the door in ugg boots and a navy paint-splattered apron. Mounted on the wall at the entrance of his home, tucked away in the bush in Sydney’s lower north shore, there are several masks and a ceremonial axe from New Guinea, the island whose landscapes are an indelible part of his art practice. He offers “water, whisky or tea” and homemade Anzac biscuits “from a friend” before pulling up a chair at the dining room table to chat about his prolific art career and his imminent achievement of turning 100.

What was the very first piece of art you made?

The first critic I can remember was my kindergarten teacher. I remember her taking me on her lap and telling me it was “a very rude drawing”. It was the sort of thing a five year old would draw. I can’t remember (what it was) now.

How did your art evolve from that unfortunate early feedback?

I’d always drawn as a child and I remember doing a watercolour when I was shortly out of kindergarten. I remember painting a green field and wondering why I had painted the whole damn thing green because there were other colours in [the landscape] as well. I must have had some sort of critical view of what it should be like. I’m probably embarrassed at telling the same story over and over again but I had to leave school at 14 for various reasons, mainly because it was the Great Depression and my old man was out of work. I got a job on The Bulletin magazine and started drawing. The art editor took me to class around the corner from The Bulletin and told me to learn to draw. That’s how it all started I guess.

Are you working on something now?

I’m working on something every day. I’m working on some watercolours and there are a couple of canvases in [my studio] that are half finished. Most of my work is about the relationship between the landscape and the people. It’s about humanity and the land, I guess.

Why did the landscape of New Guinea – where you served in World War II – leave such a strong imprint on you to the point that it has been a feature of your art throughout your career?

Because it’s an incredibly beautiful place. I’d never seen anything like it. I started off falling in love with rainforest. I had to do a jungle warfare training course in southern Queensland in rainforest country; rushing streams, mountains, hills, thick rainforest. Some of the guys I was with hated it, but I thought it was great. A rainforest is a little bit like a painting. It seems to be flat. But then as you look through it, you see there is leaf over leaf over leaf. And then occasionally you see space between the leaves. And then you get these vines that wind through the space like a three-dimensional drawing. Years later, my wife Joy and I bought a block of rainforest down on the south coast of New South Wales in Jamberoo.

After the war you studied at the National Art School in Sydney before moving to London but you still ended up painting New Guinea. Did the contrast of being in London help clarify what you really wanted?

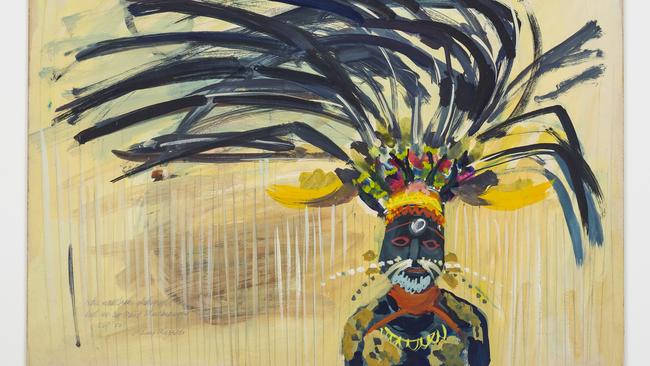

It did, absolutely. I found it difficult to paint the English landscape because it was all like a very big beautiful park. It wasn’t my sort of landscape. I know Australian land very well. I’ve probably slept on every damn sort of soil we have here. Without thinking about it I started painting my memories of New Guinea during the war. That’s when I saw a documentary on our little black and white TV of some bloke who had been to Mt Hagen and the highlands of New Guinea where there’s a big dance festival every few years. The costumes were just so immensely inventive; feathers, flowers, mud masks. I thought my God this is exactly what I’m trying to remember and paint. So I wrote to the BBC and said, “You must have had a still photographer there, can I buy some of your photographs?” I got a call a week or so later from some bloke who said his name was David Attenborough and would I like to come over for a drink.

What was he like when you met him?

Very bright. My wife and I went around for drink. He asked what we would like. I said I’d like a whisky. He poured me a fairly small whisky and said, “What would you like with it?” I said, “Well, actually, I prefer it neat.” So he put a considerably bigger amount in. I mean, that’s not important, but it’s just how odd it is that one remembers totally unnecessary, insignificant things.

Do you ever get nostalgic about things like that?

I get nostalgic about not being 35. Or 40. Or 45. I get nostalgic about youth. I’d like to be young again. I’d like to start all over again.

If you could start over, do you think you would actually do anything differently?

I would follow other interests as well. I would probably learn a language or two. I would do music. And I would probably write more. But I guess I’ll always paint because I like making marks and making marks on a flat surface is a primal urge since someone picked up a burnt stick from a fire and made a mark on a cave wall. A mark doesn’t mean anything. But it also means that I am human. And then of course somebody started seeing what other marks they could make and their wife probably said, “You should pop a couple of ears on that or a tail.”

What influence did your wife Joy, who died in 2011, have on your art practice?

She was wonderful, a great supporter all my life. She was a ceramicist and a very good one. She was also a very good academic. The sort of person who got a PhD in their 70s. I should have done something like that. I wouldn’t want to be an academic but it’s not too late. Maybe I should.

Well it’s good to keep learning, right?

Of course it is! Curiosity is the thing that drives us all on. What is around the corner? How can I do this better? Would it be better if I did something else? Or, of course, we’re all consumed with doubt about what we do. Talking about doubt, there are two comments pinned on my wall there about doubt. From painter Philip Guston: “Doubt is the acute awareness of the existence of an alternative.” (And) from Robert Hughes: “The greater the artist, the greater the doubt. Perfect confidence is granted to the less talented as a consolation prize.”

Wow, the first is a killer – there are always alternatives and you have to commit to something.

Yes. You have to commit to something. But because we are critical of what we do we always have doubts about it. You’re more critical about your own work than you are about other people’s work.

Is there anything you’re trying to perfect in your art practice at the moment?

You can always be better. One always knows there’s a great one just around the corner. But one never quite achieves it. You keep on trying and learning.

Soon the entries for the Archibald Prize are closing. You won the prize back in 1985 and you’ve also been painted several times by other artists …

There are at least three artists painting me for the Archibald this year [laughs]. If they all get in there will be several portraits of Guy Warren.

In recent years there has been some criticism of entrants who paint from photos. What’s your take on this?

I don’t like the idea of painting from photographs, particularly if it’s a human body. Photographs are flat for a start. You’re three dimensional in three dimensional space. I can see the form of your head. I know there’s air going around it. Your head has light, shade, form. If you paint from a photograph, you’ve got none of this information, you’ve simply got a flat image, which has got little relationship to the formal qualities of that particular body.

By the time this interview is published you will be 100 years old.

[Guy taps his palm on the wooden table several times] I don’t know how that’s happened. I have no way of pointing a finger at anything. I have no knowledge. I had a grandmother whom I never knew and I’m told she lived til she was 90. But my parents certainly didn’t. My brother certainly didn’t. So I have no idea. Sheer bloody luck.

From the Mountain to the Sky: Guy Warren Drawings is showing at the National Art School, Sydney, April 17-May 22.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout