Guts, but no glory in Peter Berg’s Lone Survivor

LONE Survivor is a war film - a deeply harrowing one - about a botched American operation in Afghanistan.

LONE Survivor is a war film - a deeply harrowing one - about a botched American operation in Afghanistan. But what exactly is a war film these days? Much depends on the political climate in which the war was waged. The best films about World War I tended to be anti-war films - All Quiet on the Western Front, Paths of Glory - reflecting the filmmakers’ revulsion at the slaughter in the trenches.

Films about World War II were more likely to be patriotic flag-wavers - I’m thinking of Patton, The Story of GI Joe and a host of British films from The Dam Busters to Reach for the Sky. Vietnam saw a revival of the great anti-war films of an earlier time, notably Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola’s surreal masterpiece, in which public and political disillusionment with the war found their most memorable expression.

All right, I shouldn’t generalise. But there is another kind of war film - neither pro-war nor anti-war, but designed to show us war as it really is - the agony, the suffering, the deadly routines of combat as experienced by the ordinary soldier, without glamour or partisanship. It was this sense of the tragic banality of war that made Oliver Stone’s Platoon such a shattering experience, and for me the greatest war film of them all. It is a film in which acts of heroism are driven not by idealism or patriotic fervour, but by panic and terror and an instinct for self-preservation. In Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, the combat scenes are unsurpassed for their visceral impact, their horrifying realism. In the same class, if not on the same level, I’d put Lone Survivor, written and directed by Peter Berg.

The film is remarkable for having been made at all. It is a truth universally acknowledged in Hollywood that films about the Iraq or Afghanistan wars are a box-office turn-off (despite such fine examples as The Hurt Locker, which won the best picture Oscar in 2010). Filmed in some rocky stretch of New Mexico, Berg’s film beautifully captures (at least for those who have never been there) the bleak, inhospitable Afghan terrain over which various wars, all more or less futile, have been fought by Britain, the US, Russia and the hapless Afghanis themselves. No modern theatre of war has stirred more political controversy in the West. But politics are not what matters in Lone Survivor. Berg is on record as saying he wanted to strip the film of all political relevance and concentrate on the experiences of the men in the field - in other words, to tell it like it is (or was). And in this Lone Survivor succeeds brilliantly.

It is an account of a failed mission, Operation Red Wings, carried out by a team of specially trained Navy SEALs in June 2005 with the objective of killing a Taliban leader, Ahmad Shah. (The phrase “terminate with extreme prejudice” as a euphemism for assassination, famously used in Apocalypse Now, must be out of favour.) The SEALs’ advance team consists of four men, and as the title gratuitously makes clear, only one lived to tell the tale. This was Marcus Luttrell, the team’s chief sniper, whose best-selling memoir of the operation, written with Patrick Robinson, supplied the film’s giveaway title. Luttrell is played with great strength and stamina by Mark Wahlberg.

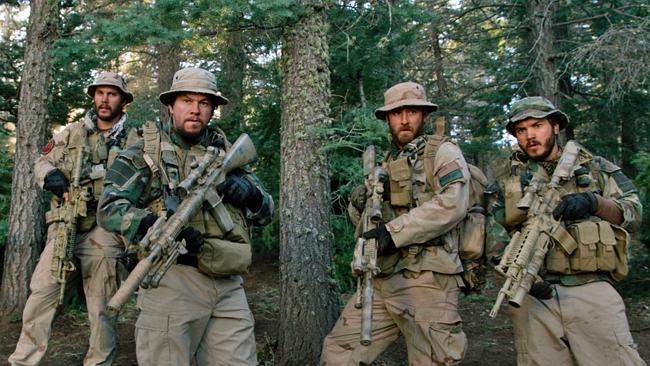

After a quick resume of the SEALs’ tough training regime - a series of brutal exercises - the men are whisked off to the front; or rather, since there is no front in this kind of war, loaded into helicopters and dumped on some flinty mountainside in the middle of nowhere. What follows is described by Luttrell (in voice-over) as “the loudest, coldest, darkest and most unpleasant of unpleasant fights”. I wish I could say we know and understand these men, that the characters come through strongly to support and sustain the action. But, really, they are little more than shadows. This is partly the price paid for any sharply realistic film shot in semi-documentary style with too little time for exposition. Swathed in heavy camouflage gear and identical facial stubble, and often half-hidden when they take cover from flying bullets, it is hard to tell the men apart, let alone distinguish their personalities. But this must be Danny Dietz (Emile Hirsch), the team’s communications man, whose radio and satnav devices keep giving trouble. Yes, that’s Eric Bana, unmistakable, at least to Australian audiences, as Lieutenant Erik Kristensen, the “quick reaction force commander”. And those who saw Berg’s last film, the sci-fi alien invasion yarn Battleship, may recognise Taylor Kitsch as Lieutenant Michael Murphy, the on-ground leader and spotter for the mission.

I’m not saying the cast act badly; I’m saying the screenplay gives them little chance to act at all, to develop the nuances and subtleties that give the best action films their humanity. You sense this in the scene when the men confront their greatest moral dilemma.

Having tracked down their target and decided to move to a more sheltered spot before killing him, they encounter an old goatherd, who wanders past them with a few goats and two young goatherds, one of them a child. The three are captured and a debate follows about what to do with them. Rightly, the SEALs spare their lives and let them go, knowing their own position on the mountain will be quickly reported to the Taliban.

Sure enough, the SEALs are soon bombarded with mortars while Taliban fighters emerge from the trees to engage them in a deadly gunfight. This battle, the film’s central and longest sequence, is thrillingly done. The shots of men tumbling downhill before crashing into rocks or trees must have taken a heavy toll on stunt doubles. And a special Oscar is surely due to the make-up artists for all those cracked skulls and gaping flesh wounds.

A more politically oriented film would have told us more about the Taliban and their evil ways. In The Kingdom, Berg’s last film about US confrontation with Islamist extremists, the plot turned on the efforts of US Special Agent Jamie Foxx to negotiate with militants in Saudi Arabia. Unlike Lone Survivor, it was a film in which politics took precedence over action.

And if I may be forgiven the sin of self-quotation, I wrote of it in 2007: “The Kingdom lacks any depth of characterisation in the secondary roles ... The filmmakers rarely allow us a moment to observe their faces or listen to their words.” The same must be said of Lone Survivor.

But for all its flaws it is both a gripping action thriller and an unforgettable depiction of the cold realities of war. My first reaction after seeing it was a simple one: this must be how it was. It may be the highest tribute I can pay.

Lone Survivor (MA15+)

3.5 stars

National release on Thursday