Gripping drama Bali 2002 recalls the terror of the time

The horror of the 2002 Bali bombings and the aftermath is graphically dramatised in a new true-crime series.

A little before midnight on Saturday, October 12, 2002, two suicide bombs tore through Paddy’s Bar and the Sari Club in Kuta, the bustling tourist heart of Bali’s beach culture, killing 202 people including 88 Australians and injuring many others.

Terrorism had arrived at Australia’s most popular overseas holiday location, a beautiful destination still known as the “island of the gods”. By the early 2000s, though, it had become a place of low-end bars, dance floors, neon signs, gutters crammed with mopeds and big-screen TVs showing vintage AFL games, where young Australians drank and danced until the sun came up.

The attack shocked us all at home, even as a bunch of everyday heroes were still engulfed in the fiery chaos to rescue their friends, and then tried to find some solace from the overwhelming despair of that fateful night.

Many of the injured, suffering terrible chemical burns, were airlifted to the unit run by burns specialist Fiona Wood at Royal Perth Hospital, who had developed a new treatment for treating burn victims – spray-on skin.

The rise of homegrown terrorism created political problems for the Indonesian government and more immediate complications for the investigating teams of the Indonesian and Australian security forces who worked together to capture the terrorists before they could strike again.

Inevitably, tension emerged between the two investigative teams over questions of jurisdiction and responsibility.

The Australian Federal Police was forced to evolve its organisation overnight as it worked quickly to assemble expert investigative and forensic teams, as well as victim identification, media and family liaison units. The inquiries proceeded against the background of people with severe and deteriorating injuries, and many with ongoing mental problems. Would any form of justice be able to bring about healing and redemption?

This is one of the many big questions at the centre of the compelling new series Bali 2002 from Screentime, produced by the vastly experienced Kerrie Mainwaring, whose credits include Peter Allen: Not the Boy Next Door, Catching Milat, INXS: Never Tear Us Apart and Brock. Executive producer is the veteran filmmaker Tim Pye whose career includes such fine TV shows as My Life is Murder, Love Child, Changi, and Old School.

Developed through comprehensive research and interviews with numerous survivors, investigators, medical personnel and people affected by the tragedy, the series is written by Pye, alongside Justin Monjo, Kris Wyld, Marcia Gardner and emerging screenwriter Michael Toisuta, with Balinese writer, actor and musician Ketut Yuliarsa (Janggan) as story editor. The production represents an unusual and obviously rewarding collaboration between Australian and Indonesian creatives.

The set-up director, establishing the production style and the cinematic aesthetic, is another TV veteran, Peter Andrikidis, also a co-producer, aided by his long-time collaborator, cinematographer Joe Pickering. His co-director is Katrina Irawati Graham, whose Indonesian ghost story, White Song, is part of Australia’s first all-female-directed horror anthology, Dark Whispers, currently screening on SBS.

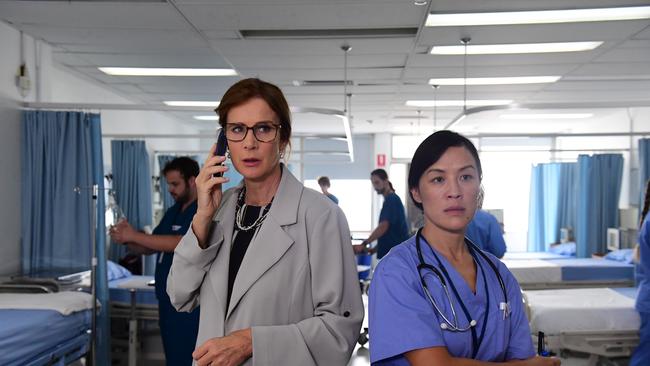

The stellar cast is led by Rachel Griffiths (Total Control) and Richard Roxburgh (Rake), featuring with Claudia Jessie (Bridgerton), Sean Keenan (Nitram) and Ewen Leslie (The Gloaming). They appear alongside a diverse group of Australian and Balinese actors, including Anthony Wong (The Commons), Maleeka Gasbarri (The Heights), Gerwin Widjaja (The Code) and newcomer Sri Ayu Jati Kartika.

Pye says the challenge was to honour all of those people involved in the tragedy within the generic restrictions of a four-hour television drama. After researching the story – rather like cold case investigators, looking at theories, prejudices, frustrations and breakthroughs, and conducting numerous interviews – the writing team decided to focus on a group of real-life stories. When intertwined and intersected they become representative of the experiences of those so viscerally affected by the attacks.

There’s Jessie’s British survivor Polly Miller, Keenan’s well-known Australian footballer and survivor Jason McCartney, and Nicole McLean (played by Elizabeth Cullen) dragged out of the wreckage of Paddy’s Bar, critically injured, by her best friend Natalie Goold (Sophia Forrest).

Roxburgh is Graham Ashton, the Australian Federal Police vice-commander, who partners with Indonesian authorities to find the terrorists. Sri Ayu Jati Kartika is Balinese mother of two Ni-Luh Erniati whose husband is initially lost in the blasts, and Griffiths is Fiona Wood who treated survivors flown back to Perth in the aftermath of the tragedy with her groundbreaking skin technology.

The production was filmed in a recreated central Kuta, designed by Tim Ferrier and situated in an empty industrial lot in Western Sydney, including popular Poppies Lane and post-explosion Sari Club and Paddy’s Bar locations.

The story of the attacks dramatised in this high-end true crime series is enormous in scale, taking place in many locations. The almost impossibly sprawling production is held together by Andrikidis’s astute and compassionate direction. Inventive, energetic and seemingly tireless, Andrikidis has been responsible for some of this country’s best TV drama, usually with the hyperactive Pickering behind the lens.

But for all his hours of direction, this project has obviously affected him more deeply than others.

“As hard as these stories are to dramatise, it is an important reminder for people of coming generations to learn from the past, so that we never see this happen again,” he says. “The worst and most tragic moments in life can actually bring the best out of people and they rise to the challenge. All the real people involved wanted to tell their story authentically, warts and all, so we can come to some understanding of the cause and effect of terrorism. We learn from the past – and nothing is ever black and white.”

The first episode, appropriately titled Island of the Gods, given the sense of anticipation with which the young people of the story flock to celebrate in Kuta, starts with a foreboding close-up sequence featuring the luminous Ni-Luh Erniati, representing something of the eternal grace of Balinese people.

“Good and evil are balanced,” she tells us, as sounds of pool merriment, splashing and rather disorderly shouting and hooting fade. Then the young woman starts to weep. “The world cannot have good without the bad; it’s our job to keep the balance, to stop the chaos. This is a gentle island, and now I offer flowers to the gods – we should have taken leave of our guests. I’m very sorry, what did we do wrong to make the gods angry?” It’s chilling and evocative.

Then Andrikidis and his writers neatly establish the central young characters and their arrival in the holiday paradise of their dreams. The writing is concentrated and taut, giving little away, and the plot line is deceptively linear, punctuated by those highly calibrated, riveting moments and set pieces that characterise Andrikidis’s direction. As the level of excitement rises, we are taken briefly into the lives of the terrorists as they plot and indoctrinate their suicide bomber acolytes. “Let us pray for your courage,” their iman tells them.

Time ratchets through the day until we arrive at the Sari Club at around 11.10pm. The first episode then in graphic detail, sparing nothing in terms of horror, shows the destruction of the bombings and how so many made extraordinary efforts to help those affected.

People who were injured in the blasts stayed to assist others, and locals and foreigners went to the site to help. Tourists with medical skills worked with overwhelmed Indonesian medical staff at the bombsites and local hospitals, especially the Sanglah, where many of the characters in the series find themselves in the absolute chaos.

It’s a brilliantly conceived and directed extended set-piece, acted with emotionally lacerating authenticity by the committed cast.

“The bombing sequences were storyboarded by me and we used real visual effects on a purposely built outdoor set with limited CGI,” says Andrikidis. A storyboard is a graphic representation of the script, divided into sequential scenes or panels, indicating the way it may look when acted out. “This enabled the actors to be fully immersed in an authentic situation and react accordingly,” he says. “All scenes were fully planned and choreographed with three cameras. Actors were allowed to fully improvise. Understated performances are enhanced from improvisations in rehearsals.”

Andrikidis, whose work with cinematographer Pickering is almost supernatural – “We talk to each other telepathically” – creates a distinctive aesthetic, alternating between multiple cameras and the use of long telephoto lenses, and subjective, extreme close-ups of his characters.

Pickering’s camera is almost like another character at times, observing but also part of the action. “I was trying to get a feeling like we were going live to air in 2002 and the use of archival footage enhanced that feeling,” Andrikidis says. “I wanted it to be immediate and not retrospective and judgmental.”

The horrifying archival footage following the explosions seamlessly blends with the new coverage, adding to the noirish, nightmarish sense of hysteria. It will be something of a relief to follow the rehabilitation journeys of those who survive in the final three episodes, and the immersive police investigation.

Bali 2002, streaming on Stan from September 25, all episodes available.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout