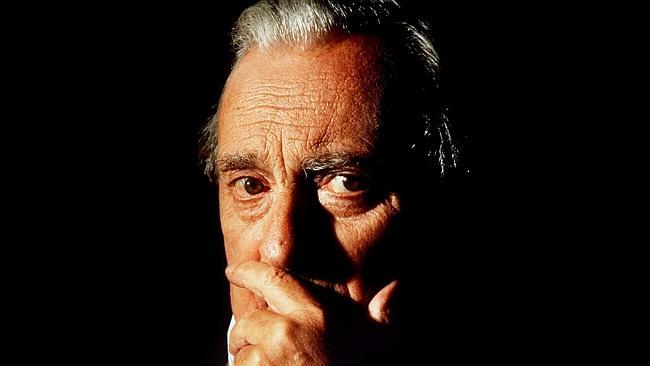

Gore Vidal: Jay Parini paints a grand but imperfect portrait

Jay Parini’s biography of Gore Vidal is a poignant portrayal of a great man descending into decrepitude.

The year 1968 was a tumultuous one for the US. The war in Vietnam was a mess, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King were assassinated and there were the chaotic Republican and Democratic conventions to choose presidential candidates. Taking advantage of this pivotal time, the ABC television network decided to broadcast eight debates between William Buckley and Gore Vidal.

Buckley was a conservative writer and the founding editor of National Review. Vidal was a novelist and screenwriter whose scandalous, campy novel Myra Breckinridge, about a transsexual who anally rapes a man with a dildo, had recently become a bestseller. He was a progressive liberal whose politics were at odds with those of his opponent.

Viewers may have been expecting a lofty series of debates between two public intellectuals but what they got instead was heated scraps between two men who could barely disguise their contempt for each other. Vidal, with a patrician voice and pompous attitude, set out to needle Buckley in an attempt to make him lose his temper. When Vidal called him a crypto-Nazi, a furious Buckley snapped back, calling him a ‘‘queer’’. Vidal’s reaction was priceless. He retreated into almost a Zen calmness, allowing himself only a sly smile of victory. He had set out to break Buckley and had succeeded.

At that moment all pretence at civil discourse was gone and the debates degenerated into name-calling and insults. In other words, for the huge audience of 10 million viewers, this was riveting and unforgettable television (watching these debates on YouTube is a hoot). Vidal may have been well-known before, but now he was famous. Having sought fame since he his youth, he would go on to become one of the most famous American authors of his time.

Biographer and novelist Jay Parini has written the first biography of Vidal since his death in 2012 aged 86. Parini was a longstanding friend of Vidal and so is in a good position to help us understand the man. Unfortunately his decision to open each chapter with a personal vignette doesn’t inspire confidence. His encounters with the ‘‘Maestro’’ are occasions where Vidal uses him as a gofer, a potential biographer and rapt listener who is not allowed to interrupt. Parini’s friendship with the novelist Joyce Carol Oates means he omits Vidal’s notorious put-down: ‘‘Joyce Carol Oates, the three most dispiriting words in the English language.’’

Despite their relationship, Parini attempts to provide an objective biography of a great narcissist. Vidal’s father, an athlete who became a successful businessman, married the beautiful daughter of the blind Democratic senator Thomas Gore. Husband and wife fought constantly; Vidal’s mother, an alcoholic and promiscuous woman, coldly ignored her only child. A troubled mother invariably creates a troubled son. Vidal sought solace in the company of his adored maternal grandfather. He would read to him, and watch him in the Senate, learning the importance of political rhetoric and realising that great politicians are gifted actors.

From his early days Vidal was convinced of his destiny as a famous writer, or even as president. Although he was to later boast that he came from a distinguished lineage, he was born into a nouveau-riche household. He was a precocious author, writing his first novel, Williwaw, based on his World War II service as first mate on a ship, when he was 21.

It was his third novel, The City and the Pillar (1948), that made his name with its frank depiction of gay life, a theme that led to the book being banned in Australia.

Vidal’s attitude towards homosexuals was ambivalent. He liked to say he was bisexual and called gays ‘‘degenerates’’ and ‘‘fags’’. He had a prolific sex life (‘‘I’m always the top, never the bottom’’) and lived with a man for 50 years in a celibate relationship. He liked to live in a grand style and although his novels sold well they didn’t provide as much money as he craved. He churned out thrillers under different names and wrote copious articles, but then discovered he had a talent for television drama. He was prolific, and it paid handsomely. He went on to become a hack movie writer, earning a fortune.

His liked to think he was a political player, running once for congress and then for the Senate. He bragged he was close friends with John F. Kennedy but was banned from the White House for bad behaviour on the one occasion he was invited there. After that the Kennedys were enemies. This became a feature of Vidal’s life. He was thin-skinned and held lifelong grudges. His feuds with ‘‘sissy boy’’ Truman Capote and the boorish Norman Mailer were legendary. His narcissism grew worse and his study walls were covered in framed magazine covers depicting him.

He may have failed to become a politician but he found his perfect platform in the essay. Over 50 years he proved himself a master of the form. Be the subject literature, politics or America itself, he was savvy, witty and cutting. He dragged authors such as Dawn Powell out of obscurity and became a consistent critic of the military-industrial complex and the US obsession with war.

He was prescient in many ways. In 1989 he published his first essay on the demonisation of the Islamic world, which he correctly foretold would take the place of the collapsed Soviet Union as America’s enemy No 1, since the national security state required a fresh enemy: ‘‘One billion Muslims and the Arabs in particular would make a fine new evil empire to oppose.’’

Vidal would go on to write a series of historical novels on topics ranging from Lincoln to Hollywood in the 1930s. It’s difficult to understand why these were so popular. The characters are two-dimensional and the history is laughable. He considered he was the equal of Saul Bellow, the only author he truly respected, and could not understand why the English in particular preferred his marvellous essays.

Parini agonises over Vidal’s reputation as a novelist and admits the fiction probably won’t last. He is also uncomfortable with his friend’s increasingly crackpot theories and enthusiasms. Vidal believed the George W. Bush administration was in on 9/11 and that Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, who killed 168 people, was ‘‘a noble boy’’ and existential hero.

It’s in writing about such matters where Parini shines. His description of his friend’s final years, when his brain became befuddled with alcohol and his monologues became increasingly loony, is devastating.

Vidal became a man out of time. His favourite pulpit, TV, now wanted inane celebrities, not public intellectuals.

Parini acknowledges all of Vidal’s faults but you cannot help being moved by the biographer’s poignant portrayal of a great man descending into decrepitude and alcoholic senility. There will be more objective biographies of Gore Vidal but this is an impressive start.

Louis Nowra is a novelist, playwright and screenwriter.

Everytime a Friend Succeeds Something Inside Me Dies: The Life of Gore Vidal

By Jay Parini

Hachette, 465pp, $55 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout