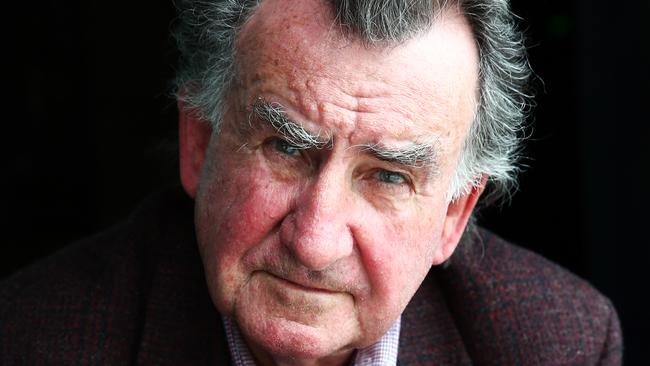

Gerald Murnane’s Collected Short Fiction: setting memories free

Gerald Murnane’s new short fiction melds his two earlier collections along with newer and sundry pieces.

Gerald Murnane’s Collected Short Fiction covers 30-plus years of his career, gathering the substance of two earlier collections along with newer and sundry pieces. A house of fiction with a multitude of windows, then, though each opens on to the same obsessively ordinary world.

Every narrative contained here is the work of a strict grammarian, containing sentences as tidy, logical and correct as a bureaucratic white paper. Yet there are also passages that are as unashamedly exquisite as poetry.

Similarly, just as every story insists on the dubiousness, even the impossibility of fiction as it is usually attempted by other literary practitioners, each seeks nothing less than a transformation of the local reality that is described.

This is where Murnane’s reputation as an eccentric and a visionary lies: in the tension between the bounded punctiliousness of his writing — its frugal store of subjects, its resolutely constrained geography — and the vaulting ambition his various narrator-masks announce for it. This collection, with its multiple recapitulations of the Murnanian method, offers an ideal opportunity to see the author’s approach in the round.

Murnane’s quasi-stories, like his quasi-novels, or quasi-autobiographies, are characterised by an incantatory use of repetition and a humour so deadpan that it represents something closer to philosophical method than a routine designed to charm: a process we still associate with Samuel Beckett. They are also fixated on image and memory to a degree that inevitably recalls Marcel Proust.

A book Murnane has doubtless read is Beckett’s first: a monograph on Proust that displayed the younger writer’s genius in brooding, undergraduate embryo. Beckett described the method by which Proust achieved his extraordinary effects. He explained how memories, if permitted to sneak up on us by accident, can open a wormhole between past and present that simply annihilates time. The earlier memory arrives like a vase of frozen flowers returned to room temperature, their old scent mingling with the air of the present.

‘‘The identification of the immediate with past experience,’’ writes Beckett, ‘‘the recurrence of past action or reaction in the present, amounts to a participation between the ideal and the real, imagination and direct apprehension, symbol and substance.’’

Take Murnane’s opening story, When the Mice Failed to Arrive. Its unnamed male narrator (all characters in Murnane’s short fiction are nominally bereft), who bears close resemblance to the story’s author, recounts a series of seemingly unrelated incidents and the thoughts or feelings that follow in their wake: concern for his school-age son during a thunderstorm one afternoon, decades before; his memories of particular illustrations in an old edition of Arabian Nights; the rehashing of a humiliating period as a schoolteacher; a conversation with his son about the boy’s chronic asthma; and so on.

The variation in time and place, and the movement between persons, objects and events seems chaotic at first: mere dream flotsam, unbidden data from the past. And yet images begin to recur and multiply in meaningful ways. The titular mice, for instance, that have featured in some small way in both son and father’s existences, are twinned as mental images in such a way as to suggest something about the thwarted nature of both their personalities.

The story ends up speaking of masculine responsibility, the darkness of sexuality, the tragic vagaries of heredity. It becomes an admission of frailty, or failure; an expiation of guilt. And its emotional force arises precisely from its refusal to approach its subject matter head-on.

This obliquity is not just a late modernist’s tactic for complicating form; it is a more primal social inheritance. In Cotters Come No More, the narrator visits his bachelor uncle on his farm in Victoria. Much of the account is given over to the narrator — a young would-be writer — and his self-consciousness in relation to this laconic cocky, with his old-fashioned tastes in poetry. After a passionate defence of DH Lawrence’s free-verse experiments, he falls silent:

My uncle did not bother to untangle my propositions. He simply told me that his father, my late grandfather, had said about some men that instead of talking they opened their mouths and let the wind blow their tongues around.

As the pages accumulate behind the reader, this sense — that Murnane’s weird narrative evasions and elisions are less ‘‘literary’’ effects than coping mechanisms for an anxious, embattled subjectivity — only grows. For a man driven by ambition and physical urges at variance with his upbringing, with its conservative rural mores and ingrained Catholicism, the decision to leave the church and instead write secular fictions (and to entertain the possibility of ordinary human passion) are bound up at the root.

Indeed, the narrator of The Interior of Gaaldine gestures towards such a possibility. This story is the account of a Victoria-based author who is invited on a week-long writers’ event in Tasmania in the early 1980s. The only impediment to acceptance is the fact the author has never flown and, in fact, has only ever left his home state twice. So the organisers book our narrator on the Bass Strait ferry instead, and he girds his loins to leave his family home on an extended trip for the first time in 20 years.

What follows is an ordeal of metaphysical dimensions, transcribed with the wounded confusion of a trauma survivor.

The narrator drinks his way through the crossing and shuts himself immediately away at the Devonport hotel where he is being put up ahead of the events.

Then a mysterious woman comes to his room, pressing a manuscript on him that purportedly belongs to an unpublished Tasmanian writer his own age. His recollection of the manuscript and the author of the work provokes a crisis in the narrator — and an explicit accounting of his own creative aims. ‘‘I have always been interested in what is usually called the world but only insofar as it provides me with evidence for the existence of another world,’’ he admits.

I have never written any piece of fiction with the simple purpose of understanding what I might call the real world. I have always written fiction in order to suggest to myself that another world exists. And whenever I have read a piece of fiction that seemed to me worthy to be read, whether the author of that fiction was myself or another person, I have always read with the purpose of suggesting to myself that a world might exist beyond the world suggested by the fiction, even if that further world was suggested only by such passages in the fiction as a report of the narrator’s reading a text that he could not understand or of a character’s dreaming a dream that was not reported in the text.

This key passage strikes the reader as being a theological gesture trapped inside a literary aesthetic. It is a story that refers outwards, to the web of Murnane texts that surround it, and speaks to the intense private pressures from which his many words have been spun.

Vladimir Nabokov, another author who pursued an idiosyncratic personal theology, determined that God exists because the camouflage on a butterfly’s wing seen under a microscope was so perfectly done, so in excess of evolutionary requirement, that it must be the work of an artist. What Collected Short Fiction reveals is that Murnane, too, has long been looking for icons of the ineffable in unlikely places: in the racing colours worn by jockeys, in the colour of the sky above Ballarat, in the swirl at the centre of a marble or the torn white paper on which mice are bred. It was not within the images that Murnane hoped to find some absolute, however; it was beyond them. As Murnane announced in a recent interview:

“All the fiction I ever wrote or read was a preparation for this, my true life’s work. In book after book of mine, I wrote about the contents of my mind, setting all my images on paper so that I could have done with them; could sweep them out of sight and leave my mind free for the infinite imagery of the Antipodes.’’

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

Collected Short Fiction

By Gerald Murnane

Giramondo, 480pp, $34.95