From Virgil to Hitler, riches in the Ruins

Julia Hell is a professor of German literature at the University of Michigan’s College of Literature, Science and the Arts.

Julia Hell is a professor of German literature at the University of Michigan’s College of Literature, Science and the Arts. Her interests are wide-ranging. She teaches undergraduate courses on: The Third Reich and its Legacies; Introduction to German Literature: The Family; and 20th Century German Philosophy. She also convenes graduate seminars on: Realism: Theory and Aesthetics; German Colonialism; Hauntings: A Seminar in Psychoanalysis; Trauma and Cultural Analysis; Post-Fascist Cultures; Ruins; and German Political Theory: From Weber to Schmitt. A great deal of all this is reflected in her new book — not least the questions of ruins and what she calls “ruin gazing”.

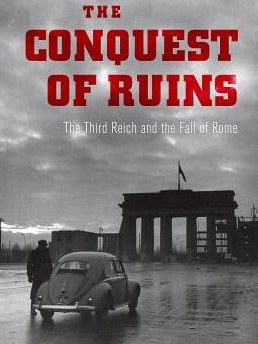

The Conquest of Ruins has an introduction and six multi-chapter parts. The introduction is titled “Neo-Roman Mimesis and the Law of Ruin”. Part One is “After Carthage: The Roman Empire and Its Ruins”. Part Two is “Neo-Roman Mimesis: Charles V at Tunis: 1535”. Part Three is “Neo-Roman Mimesis in the Modern Age: Cook’s Second Voyage to the South Pacific and the French Conquest of Egypt and Algeria”. Part Four is “From Germany’s Anti-Napoleonic Barbarians to the Ruin Gazer Scenarios of the Conservative Revolution”. Part Five is “With the End in Mind: The Nazi Empire’s Neo-Roman Mimesis and the Ruined Stage of Rome”. Part Six is “Romans or Greeks? Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger”.

This is rich stuff and well worth the read. There are a handful of solecisms, owing to copy-editing oversights, one assumes: a Pope Leo XIV appears in both an endnote and the index, though there has been no Pope Leo XIV. It would appear that Hell meant Leo XIII (1878-1903). She has the Emperor Constantine visit Rome in 357 CE, though he was long dead by then and it was his son, Constantius II, who made the visit. She consistently misspells the name of the Emperor Septimius Severus as Septimus Severus. At several points she has endnote citations from Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals that fail to specify which of its three parts the citations are drawn from. These are minor, if surprising, distractions.

Overall, the interweaving of textual analysis, art history and politics is impressive and fascinating; her erudition and mastery of her sources breathtaking.

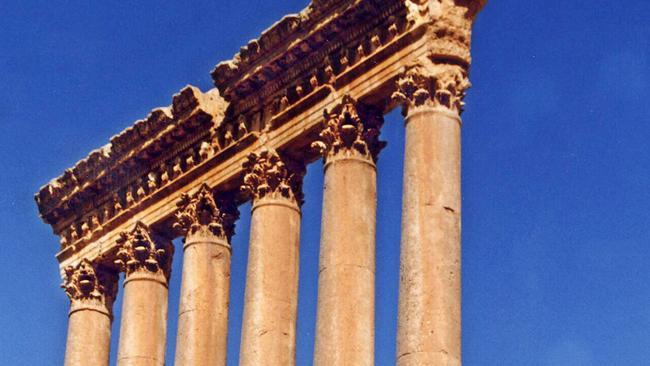

Given the gridlocked debate in this country over the past few years over whether or not it is acceptable to teach a Bachelor of Arts in Western Civilisation at our leading universities — or any of them, for that matter — Hell’s book might well serve as a circuit-breaker. She paints an unforgiving portrait of the Roman Empire as brutal and supremacist, while arguing that it has haunted and inspired European imperialists ever since — right down to the Nazis. The “ruin gazers” over the centuries both longed to build an empire like the Roman Empire and envied the romantic lustre of the monumental ruins Rome had left behind. All this in the Lacanian imaginary.

What Hell doesn’t do is balance the ledger by telling us about all those students of the Roman Empire and visitors to Rome not motivated by imperialist fantasies, racism or a nostalgia for the military and slave-owning ways of the ancient world. Given her use of St Paul and Tertullian, it seems odd, for instance, that she doesn’t discuss St Augustine’s reflections on the Roman Empire, in The City of God Against the Pagans. Nor Charlemagne and his project of attempting to rebuild a version of Latin civilisation in the late eighth and early ninth centuries, which had him crowned emperor in Rome by the pope a thousand years before Napoleon. There is no mention of those who drew diverse lessons from the history and fate of Rome, only of those who saw it as a ruthless (and ill-fated) dominion to emulate.

In terms of balance regarding idolaters of empire versus critics of it, she might have looked at Pierre Briant’s The First European: A History of Alexander in the Age of Empire (Harvard, 2017). And with regard to visitors to Rome since the Middle Ages, she might well have read my old teacher Ronald Ridley’s three-volume magnum opus Magick City: Travellers to Rome from the Middle Ages to 1900 (Pallas Athene, London, 2017-19). But her actual approach and her omissions would, one imagines, actually appeal to the good scholars at the University of Sydney who objected publicly to the creation of a degree in Western Civilisation. Even to do what she has, however, at least requires genuine learning and her argument prompts a host of questions — the core objective of any good, liberal education. Liberal? Pardon me, I should reword that. Let’s call it emancipatory education.

No trope in Hell’s book is more arresting than the consistent evocation of Virgil’s Aeneid. This literary and rhetorical device is used masterfully. The ruins of Troy, the ruins of Carthage, the Aristotelian/Polybian idea that empires are destined to fall, existing in “the time before the end” — the anticipation of the fall of Rome, the building of monuments even at its height in the expectation they will, in time to come, constitute its ruins — all these are the foundation of Hell’s historiographic analysis.

She concludes with Hitler in his bunker in April 1945, beneath the Reich Chancellery in which Albert Speer had Aeneas and Dido tapestries placed years before, writing his Political Testament with allusions precisely to Virgil’s Aeneid. Timothy Ryback in Hitler’s Private Library (2009) made no reference to Virgil, so it comes as something of a shock to learn that, in his final hours, Hitler cast himself in the role of a self-immolating Carthaginian queen, conjuring a future neo-Nazi Hannibal to avenge his defeat. But nothing could better round out Hell’s sublime narrative. In retrospect, one can only wish this conceit had been given to the late Bruno Ganz in his bravura performance as Hitler in Downfall (2004). So, read The Conquest of Ruins. You’ll never read Virgil quite the same way again.

Paul Monk is the author of 10 books, including Dictators and Dangerous Ideas.

The Conquest of Ruins: The Third Reich and the Fall of Rome

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout