From the Wreck by Jane Rawson: a strange sage of survival

From the Wreck is based on the 1859 loss of the steamship Admella off the coast of South Australia.

Jane Rawson is an explorer of the odd. Her 2013 debut novel A Wrong Turn in the Office of Unmade Lists was a dystopian voyage into narrative implausibility, featuring a ruined Melbourne and California’s Bay Area. More recently her novella Formaldehyde (2015) featured a dead protagonist in a love triangle. Both were works of eccentric originality.

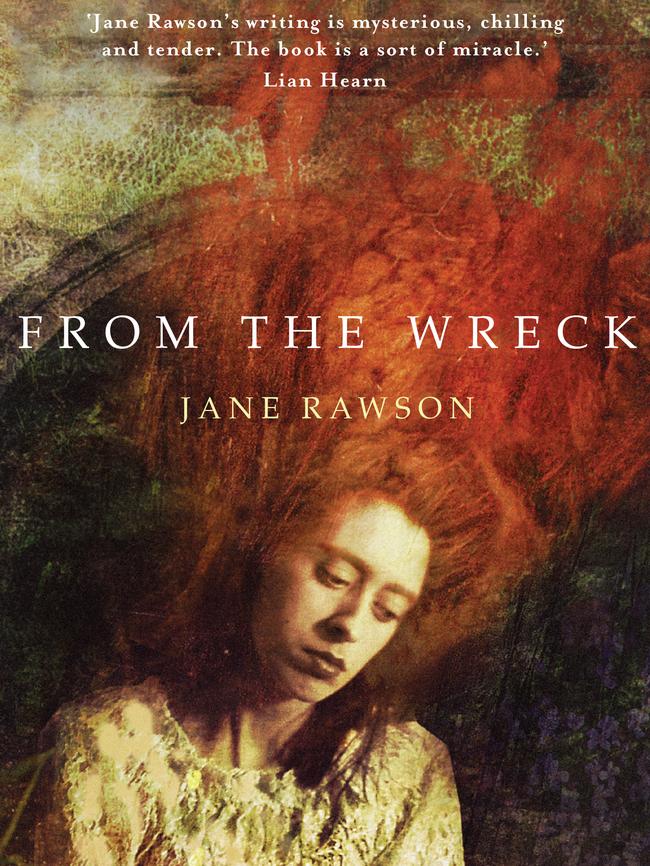

When from From the Wreck, arrived in the post, however, my heart sank a little: the cover all russet and sepia, colours of nostalgia, the slightly spectral image, the historical story with a family connection. I was concerned that Rawson, fuelled by some success but also finding her talents under-read (A Wrong Turn in the Office of Unmade Lists won the Small Press Network’s prize for most underrated book), a curse of small markets, had turned to the mainstream and that most overpopulated genre in Australian literature, the historical novel.

The historical part is true, but thankfully, Rawson hasn’t sold out on idiosyncrasy and it isn’t long before the reader finds themselves absorbed in a multi-perspectival story that is strange and affecting.

The story is based on the wrecking in 1859 of the steamship Admella off the coast of South Australia, of which the author’s great-great grandfather, George Hills, was a survivor.

Rawson plays with the truth from the outset, reducing the number of survivors of the wreck from 24 to 2, George and the enigmatic Bridget Ledwith, who is not what she seems. In addition to feeding off the blissfully wet flesh of his dead shipmates, George is also troubled by how he was succoured by Ledwith on the wreck. He has committed cannibalism and been unfaithful to his fiancee and his survivor guilt has unbalanced him.

One way of thinking about speculative fiction is that it takes ideas and extends them into realms that no longer need to be measured against reality. At first it seems that Rawson might be leading us down the path of evolutionary aberration. The early Darwinian conversation between George and his brother-in-law William is a kind of scientific red herring that leaves you wondering whether the plot is perhaps organised around the substitution of Darwinian for Lamarckian evolution, in which organisms are adaptive within their lifetimes.

But that would be too simple. The real reason for George’s survival against the odds is that Bridget Ledwith is an alien. Again, the storyline is a case of extending an idea, specifically the idea beautifully explored in Peter Godfrey’s Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness: “If we can make contact with cephalopods as sentient beings, it is not because of a shared history, not because of kinship, but because evolution built minds twice over. This is probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien.”

Why not then make the rescuer of George an alien cephalopod gifted not just with telepathy, but with its invertebrate shapeshifting ability radically enhanced. Rawson’s alien is not just a shipwreck siren with its good intentions misunderstood, but a cat, and a mark on the back of George’s oldest son, Henry. Importantly we are given the alien’s side of the story, too. It’s a creature defined not by malevolence but loneliness and it’s hard to imagine loneliness more extreme than being the only one of your kind.

Henry has a troubled relationship with his mark, whose desires are not always compatible with his. George is also troubled by its presence on his son. Somehow he is aware of its pedigree and at times he is tempted to violently excise it. A number of minor plots help thicken the story such as the fate of Henry’s younger brother George and the story of the unconventional and unflappable Beatrice Gallwey who lives with her grandson in the stables of the Hills’ abode.

In less capable hands these narrative facts would accumulate to preposterousness and tempt the reader to abandon the ship of the book. Rawson, however, has the rare talent of stretching our capacity to believe, while at the same time making us feel genuinely for the characters. There’s a beautiful quality of empathy here, light and aching, not just for the boy and his trials and tribulations, or indeed for the father, a recovering cannibal who has (in the Irish sense) been touched by his experiences, but also for the alien presence. I was reminded of the gentle quality of Steven Spielberg’s ET with its own benign alien who has been separated from his home.

The tools we have for imagining others are the same tools that we have for imagining ourselves. In looking at the octopus, Peter Godfrey is unable to come to any conclusions as to exactly how they may think and feel. At one point Henry “felt his Mark seethe and stretch, the edges of it crawling across his back, up his neck, and he wondered if today would be the day it would eat him entirely and all his problems would be gone”.

It’s a fair question: who knows what would happen if cephalopods and their alien extensions were in the position of finding us easily consumable? In giving this alien a sympathetic voice in the novel, Rawson has taken on the risks of anthropomorphism and erred on the side of kindness. Anthropomorphism is both a metaphorical bridge and a form of collective narcissism, and it is a poor tool for imagining the inner lives of other beings. But then again, it’s one of the few we have, and Rawson has used it here to create an intriguing tale whose humanity lingers warm long after the reading.

Ed Wright is a writer and critic.

From the Wreck

By Jane Rawson

Transit Lounge, 267pp, $29.95