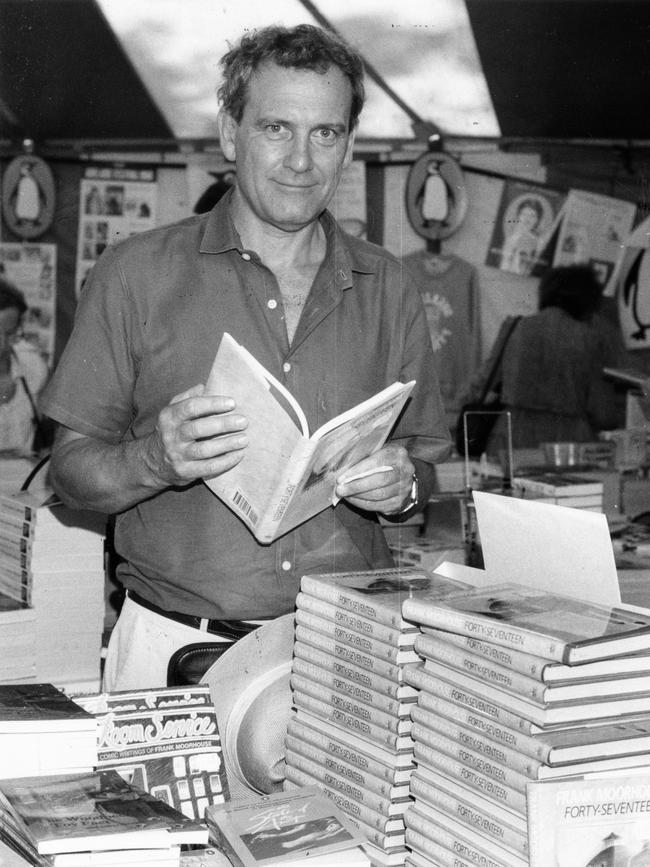

Frank Moorhouse wrote about women, sometimes dressed as one

How much of Frank Moorhouse can be found in his most famous and beloved character, Edith Berry Campbell?

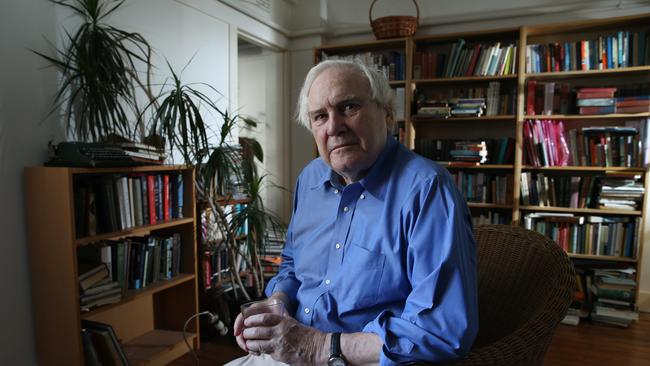

When it comes to working out what made Frank Moorhouse tick, it’s Helen Lewis, friend, bushwalking companion and now literary trustee, who sums up the challenge: “There were many rooms in Frank Moorhouse.”

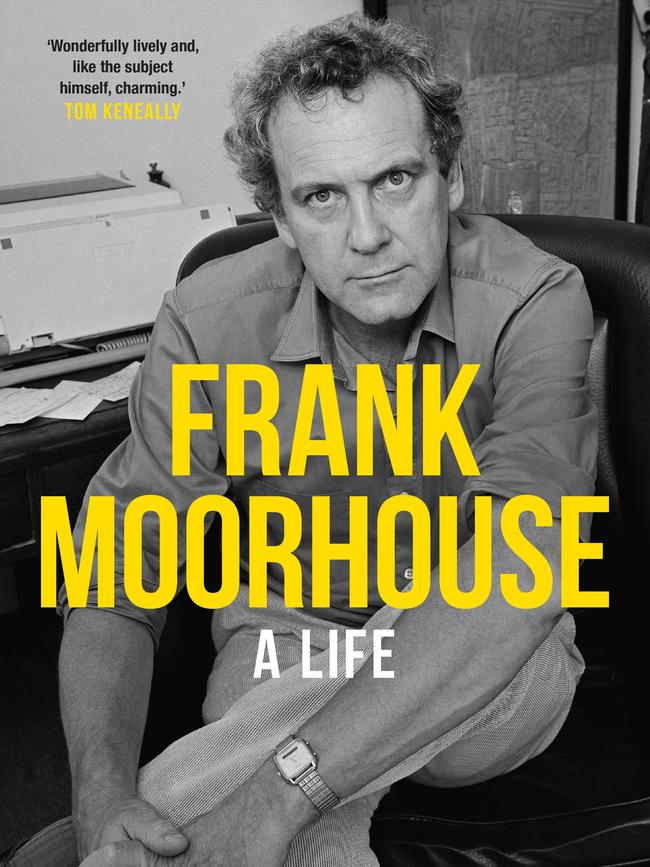

In Frank Moorhouse: A Life, journalist, writer and academic Catharine Lumby stands before the doors to those rooms. Most of them she opens but some she does not. The result is an absorbing assessment of a landmark Australian writer “whose life and work were clearly entangled and inextricably linked” and a candid examination of the ethical questions biographers face.

At 296 pages, this book is not a cradle-to-grave biography of Moorhouse (1938-2022), as Lumby admits in her admirable introduction.

“This is a selective biography. It’s written from a subjective viewpoint. This is my version of his story (and) an analysis of why I think his writing matters.”

Readers impatient for the full life have not long to wait. In November, Knopf Australia will publish Strange Paths, the first instalment of a planned two-volume Moorhouse biography by Tasmanian academic Matthew Lamb.

Until then, there’s Lumby’s rooms to the life of a writer who was a “contradiction in terms”. Let’s be frank and start with the most obvious door: sex.

Moorhouse’s love life, with women and men, is central to his life and his work, as is his interest in sexual fluidity and gender ambiguity.

“My wardrobe is two-thirds female and one-third male,’’ he told his biographer.

Lumby, and other writers, believe the feminine side of this androgynous approach to life partly explains why he wrote female characters with such empathy.

She considers his most famous one, the Australian in Geneva Edith Campbell Berry in the League of Nations trilogy (Grand Days, Dark Palace, Cold Light) a cipher of the author.

Then, this being Frank Moorhouse, she sees another cipher in Berry’s bisexual, cross-dressing English diplomat lover then husband, Ambrose Westwood.

Moorhouse did not have children. The treasure trove for this book was his vast archive. He held onto all the letters he received and to copies of the ones he sent.

Lumby interviewed him more than 20 times. His advice was to “dig up disgraceful things he’d done, forgotten about, and write about them”.

She interviewed 45 people who knew him “personally or professionally”, including several of his female lovers. However she decided not to “out” male lovers “who lived outwardly heterosexual lives”.

“I have erred on the side of caution when it comes to revealing intimate relationships documented in the archive which are not public knowledge.”

The other rooms Lumby visits include Moorhouse’s move from his birthplace, Nowra on the NSW south coast, to Sydney; his time with the Bohemian Sydney Push during the sexual, gender and political rebellions of the 70s; his general approach to writing and his passionate support of other writers; his battles with censorship; and the League of Nations trilogy.

There’s a wonderful room, The Moorhouse Method: Rules For Living, stocked with the fine food, wine and spirits the workaholic author took pleasure in. He shares his recipe for a martini, such an indispensable drink that it was the title of his 2006 memoir, and, in a passage that makes me laugh out loud, muses on how he would like to become an oyster.

“I like taking in the sun, and I like to close the lid on my life for a time and just have time out – as oysters do.” And again, this being Moorhouse, he concludes, “Oh, and they change sex every so often just for fun. I like that, too.”

The overarching theme of this book, and of its subject’s life and work, is rules, borders and boundaries – national, international, political, cultural, ethical, emotional, sexual, gender – and the decision on whether we should break or cross them and if so, how far. Moorhouse weighed that question all of his life. ASIO had a file on him but then, as he said, it had one on most writers.

Lumby astutely concludes that Moorhouse was fascinated by rules because he “liked toying with their boundaries. He was interested in worrying, rather than exceeding, their limits.”

Moorhouse had his oyster-like time outs on his long walks in the “non-verbal world” of the Australian bush. He always packed bourbon because it had the “best alcohol-to-weight ratio”. The chapter titled The Bush includes a thought-provoking analysis of Moorhouse, Henry Lawson and sexual identity. It also contains a snippet from Moorhouse’s boyhood when he accidentally slid down a tree on which he was perched and cut open his testicular sac.

There was no permanent damage, as he went on to prove. Yet Moorhouse later wondered if the fall was not an accident but an unconscious desire to emasculate himself.

Maybe. But let’s end by adapting a quote attributed to Picasso: Sometimes, Frank, a tree is just a tree, a boy is just a boy, and a ripped ball bag is just a ripped ball bag.

Stephen Romei is a writer and critic.