Frank Knopfelmacher: a humanist for our times

Melbourne University’s Frank Knopfelmacher was a sensible, independent voice in a sea of incoherence.

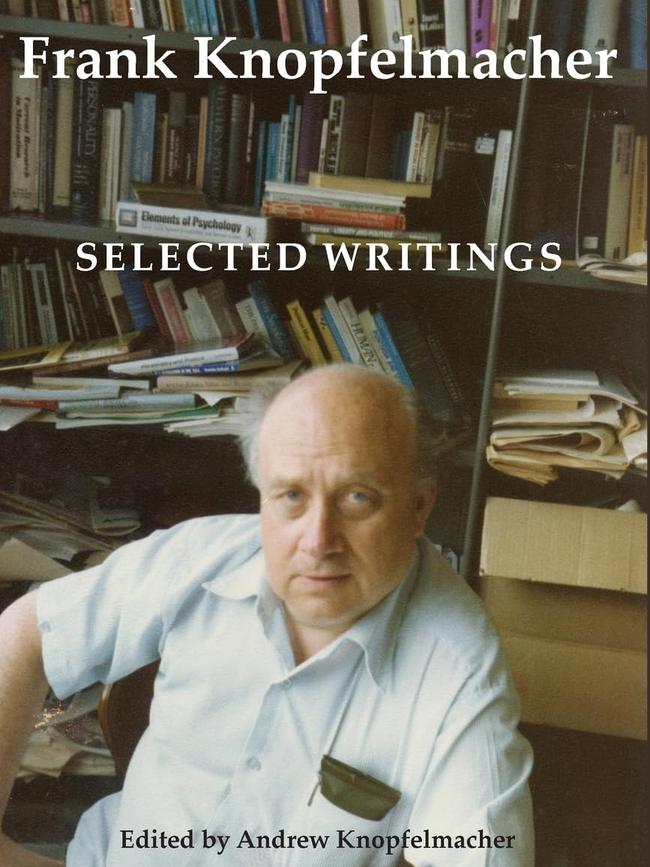

Frank Knopfelmacher – “Franta” to his intimates - was one of the best educators I ever had. I took his Classical Social Theory course in 1979. He never published a book, but this collection of his occasional papers is a treasure. Not simply for those of us taught by him at the University of Melbourne, from 1955 until the end of the Cold War, but because his coruscating wit, fearless iconoclasm, political maturity, philosophical sophistication and plain-spoken humanity are an education for young minds in the 2020s.

His is a voice of sanity and independence of judgement in a world spiralling out of control and into intellectual incoherence. These essays should be read, discussed, mulled over and shared around very widely. They constitute an accessible humanistic education in a nutshell. The book could have done with an index, but it is very accessible, essay by essay.

It contains 30 essays published between 1958 and 1993, but begins with his remarkable essay My Political Education, first published in Quadrant in July-August 1967. Perhaps neither it nor the other essays have been republished or collected since because Knopfelmacher was a bête noire to the broad Left – communists and fellow travellers.

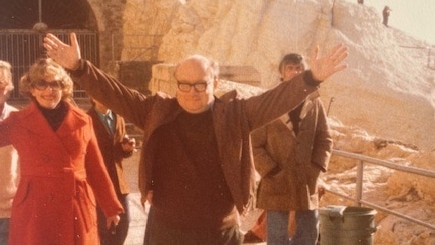

But My Political Education is precious. It shows the young Knopfelmacher (born in 1923), a Czech Jew, becoming a Marxist in his teens, fleeing Europe, in the belief that the Nazis intended to kill all the Jews (they did kill his entire family, who had not fled), then learning as he went: from a kibbutz in Palestine to the British army and combat in Normandy, to post-war Czechoslovakia and the communist coup of 1948, to Bristol for a PhD in philosophy and psychology. The PhD years and reading George Orwell, he wrote, were the happiest years of his life. Then he came to Melbourne.

I have always loved that essay. Re-reading it, however, I realised that there is far more in it than I had remembered and that I had misremembered a number of details. The other essays I had never read and there are some pearls among them. What’s in a Name, for instance, is a reflection on his family history, language, etymology and assimilation. It could be read with delight by any of millions of migrants or children of immigrants in Australia.

His essays on communism, totalitarianism and the Cold War are less museum pieces than studies in a challenge we still face in thinking through how to grapple with Xi’s China, Putin’s Russia, North Korea, the mullahs in Tehran. The Catholic Church and Totalitarianism (1961) is a wonderfully dispassionate assessment of the nature of conservative Christianity, written as the Second Vatican Council was underway, by someone who was Jewish, an atheist and a philosophical sceptic, but a thinker, not a narrow-minded ideologue of any kind.

He was concerned about the influence of communists in our universities – and they were concerned about his presence and outspokenness. Given the “radical” presence on our campuses right now, his reflections, including his often-surprising generosity to ideological enemies, make for luminous reading. The more so because the immediate personalities and issues have changed, so that the principles at issue are able to emerge more sharply.

Knopfelmacher was Jewish, but his attitude to Zionism and to Israel, to the Holocaust and the uses of it by those who had not necessarily suffered through it, as he had, in losing his whole family, are nuanced, thoughtful and morally honest. They make eye-opening reading. In the present context, with the war in Gaza so controversial, it is particularly illuminating to read The Consequences of Israel (1967). Also, his remarks about the Jewish diaspora, Hannah Arendt and the Eichmann trial and the ironical risks to Jews as citizens of other countries from being perceived as Zionists.

There is so much here to digest with appreciation over a good red or a strong whiskey. A few highlights are: America the Bad Society (1971), Terrorism and Reason (1977), vignettes on the great Czech phenomenologist and political dissident Jan Patocka, Solzhenitsyn and the fleshpots of the West, Arthur Koestler, In (Mild) Defence of Karl Marx (1983), George Orwell (whose writings greatly influenced him in the 1940s, in his transition from communism to social democratic humanism) and Australia’s British heritage.

When a student, I delighted in Knopfelmacher’s deadpan humour and dry wit. It is marvellously present in these papers. English was by no means his first language, but he developed a wonderful facility with it and his puns, his drollery, his acid asides and ironies pepper these pages. He read very widely, but never credulously or from a dogmatic point of view. His erudition shines all the more for having been thoroughly digested. He is never pretentious, obscure or pedantic.

In the lecture hall, he stood out as a man of worldly experience who had lived social theory. He introduced us to Marx and Weber, Durkheim and Tonnies, Gramsci and Michels as a means to grapple with a bewildering world, not as academic texts and never as ideological dogma. Our students badly need his wisdom. Read this book. You won’t be disappointed.

Paul Monk took a BA in European History from the University of Melbourne in 1981 and a PhD in International Relations from the ANU in 1989. He has worked as an intelligence analyst and a consultant in applied critical thinking skills and is the author of a dozen books, including Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout