For your eyes only: the man behind James Bond, Ian Fleming

Already infatuated by James Bond, the then US president became bewitched by Ian Fleming. But it was another Bond fan who would soon create his own horrific history.

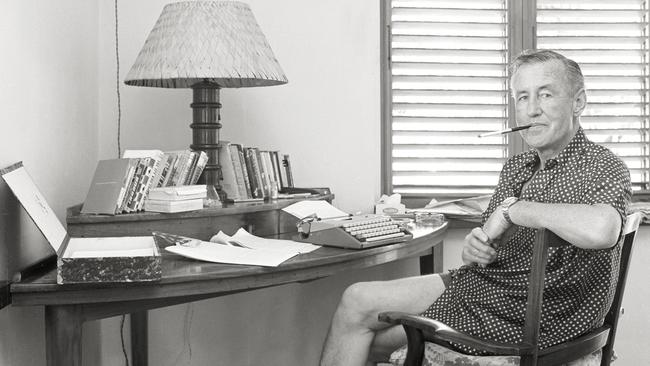

For four years, biographer Nicholas Shakespeare kept a photograph of a young Ian Fleming propped on his desk.

“He stared impenetrably at me, defying my attempts to crack him,” he tells The Australian‘s cultural critic, Peter Craven, in this exclusive interview to mark the publication of his biography of the man who created James Bond, Ian Fleming: The Complete Man.

“Only towards the end did I glance across and at once see him through the veil of his cigarette smoke, and have a sense that I understood him better.”

The Fleming that emerges from the pages of the book is greater, and kinder, than the sardonic, wife-beating caricature that emerged after he died, but as to whether Fleming was his own model for the charismatic British masterspy, do read on …

PETER CRAVEN: Ian Fleming was the grandson of an immensely rich self-made man … How would you summarise the way in which this shaped him?

NICHOLAS SHAKESPEARE: His grandfather Robert Fleming became one of Europe’s richest men after founding the merchant bank in his name; by 1928 he controlled £3 trillion worth of business in today’s money (about $5.7 trillion). Little of this trickled down to Ian. He was rich by the standards of the day, but he was associated with money more than he was ever in possession of it. Well into adulthood, he had to depend on his flighty, snobbish mother Eve for humiliating handouts. His career choices were dictated by financial concerns – he always had to earn a living, until Bond took off … but by the time he made his fortune, it was too late to enjoy it.

He dropped out of Eton, he didn’t go to Oxford or Cambridge and he dropped out of Sandhurst Royal Military Academy … he doesn’t get taken up by the Foreign Office despite meeting their linguistic criteria. Did he have to be so unlucky in order to achieve the stupendous success that came to him?

What a good question. I’m not sure he was “unlucky”. Rather, he had to pick a much rockier and steeper path to success.

The account of his role in Naval Intelligence is the central paradox of the biography. We take it on hypothetical faith that Fleming actually was the James Bond of the SIS with Admiral Godfrey as his M and he also did a great deal to set up the CIA and to establish the espionage systems of the American ally. How much do you think he was the genesis of the British masterspy – violent, adventurous, brilliant?

The former head of MI6, Richard Dearlove, says that the fictional spy’s impact has been huge, saying: “It’s made the Service the most famous intelligence organisation. It’s reputational, it’s myth-building, it’s contributed to the brand. In the most distant part of the world, everyone has heard of MI6.” There are temptations to diminish or exaggerate his contours. My favourite example of how Fleming’s role can be puffed out of all proportion is the 1997 book Op.JB, by former British intelligence agent Christopher Creighton who argued that Fleming was personally involved in capturing Martin Bormann (Hitler’s lieutenant) from Hitler’s bunker in Berlin. At the other extreme are those like Loelia Lindsay, Duchess of Westminster who saw Fleming as a desk-bound Chocolate Sailor whose chief responsibility was for “in-trays out-trays and ashtrays”.

You describe an early relationship: Fleming breaks up with a Swiss girl, Monique, after his mother Eve threatens to take away his allowance. Was Monique his one chance at emotional fulfilment?

Well, when he finally marries, 20 years later and under duress, it is to a domineering society woman identical in character to Eve … But one obvious reason he married (the British socialite) Ann (nee Charteris, who firstly married Lord O’Neill, and secondly Lord Rothermere) is because there was news of his affair and her impending divorce, not to mention her pregnancy. It was the gentlemanly thing to do. This was the second time Ann had fallen pregnant with Ian Fleming’s child. According to her daughter Fionn, her falling pregnant so soon after she left Rothermere did ensure that Ian “would have to marry for my mother to give birth to a child everyone knew was Ian’s.” It was part of his uprightness, his orthodox side, the side of the clubland hero … this time he had to do the honest thing.

Was British socialite and art patron Maud Russell’s gift (£5000, which Fleming used in 1947 to buy an old donkey racetrack in Jamaica where he built Goldeneye, the home where he wrote his James Bond novels) the makings of him?

Maud Russell’s gift of Goldeneye gave him a bolt-hole in the sun to write about a tantalising way of life that he enjoyed when he was there, away from the soul-destroying diet of an England still on rations … For 13 years on the trot, he used each visit to the island to write a book. Every January and February, he escaped the padlock of married life and spam-munching gloom of Attlee’s Britain, by retrieving his bachelor past and executing in modern form those plans which he had conceived against the Nazis. In wartime, Ian had put these ideas into life; in uneasy peace, he put them into fiction, carrying the sexual climate of the Blitz into the austerity of the Cold War.

Clearly he was an editorial genius. What would have happened to him if he had in some essential sense stayed a journalist?

He said if he were 25 again and had any choice of career, he would “go back to newspaper work”, but with a camera, and become a TV news journalist.

It’s forgotten that Fleming took a long time to become a bestseller. None of his first five Bond books sold more than 12,000.

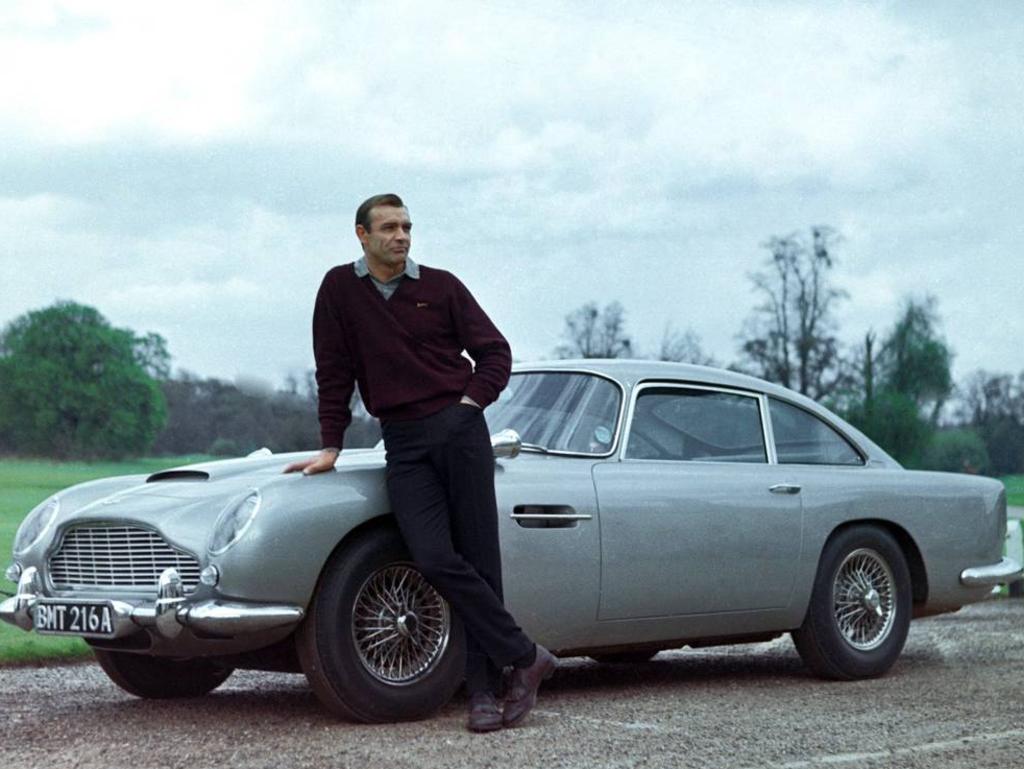

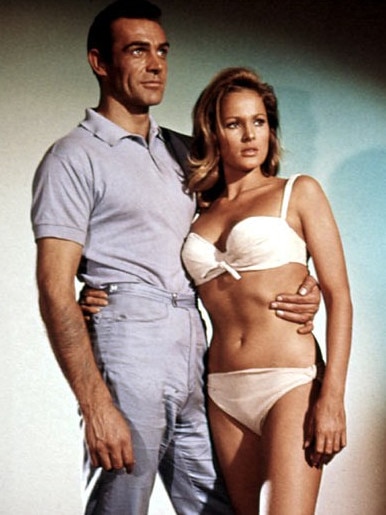

He contemplated writing Bond off in From Russia, With Love. Stabbed in a Paris hotel room by a poisoned steel blade. What rescued Bond was the Suez Crisis – after the British PM Anthony Eden decided to recuperate that November in Goldeneye, the place where Ian had conceived Bond four years earlier, while British troops landed in the canal zone, only to be humiliatingly evacuated shortly afterwards. Then the press baron Lord Beaverbrook helped to assure Bond’s revival. He offered to serialise the new Bond novel in the Express and capitalise on the publicity that linked the prime minister and Ian Fleming to the island where Beaverbrook himself had a home. Months later, the Express began also carrying a strip cartoon of James Bond. Sales among lower middle-class readers, who had been at the heart of popular support for Eden’s invasion, took off. On his next visit, instead of killing off Bond as planned, Ian plunged into writing Dr No and brought 007 swinging back. For the first time, Fleming broke through the 12,000 sales barrier. Conceived as a post-war British fantasy, as a balm for a demoralised imperial power on its uppers, Bond evolved thereafter into an immaculate agent of escapism. The lower the sun has sunk on the empire that Bond was born into, the more radiant his glow.

President Kennedy’s backing massively boosted the sales of the books. Do you actually think the handsome 41-year-old US president with the background in intelligence and the penchant for sleeping with Marilyns was an analogue of Bond?

The Ian Fleming/John F. Kennedy dinner in Washington in March 1960 was the chapter I most relished writing. So many things converge – to the ultimate success and destruction of both men. Already infatuated with Bond, JFK that evening became bewitched by Fleming. It’s easy to see why. They had shared tastes in women and literature; both had served in Naval Intelligence. And it wasn’t merely JFK who was overly influenced by Ian Fleming’s novels and engaged in secret plots. Another Bond fan was the emotionally disturbed young man who killed him.

At 9pm on Thursday 21 November 1963, a private screening of From Russia With Love was held for 50 guests in the White House projection room where JFK had watched the first Bond film, Dr No. But on this night, he was in Fort Worth, on his way to Dallas. We know what happened next … and in his assassin’s rooming house at 1026 North Beckley Avenue, detectives found two paperbacks of Live and Let Die and The Spy Who Loved Me.

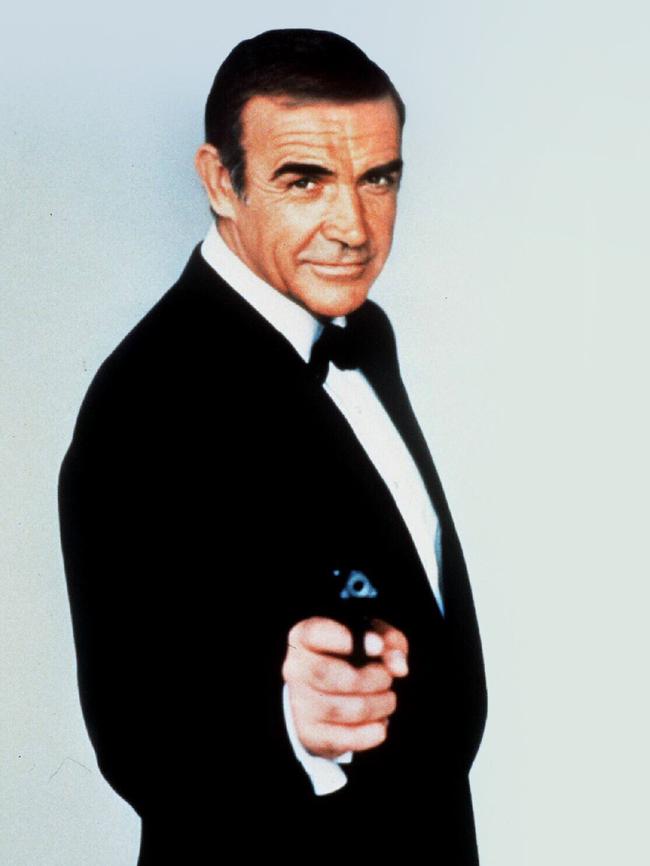

Sean Connery said he learned to play James Bond by playing Macbeth. Germaine Greer said Macbeth was the tragedy of a man who tries to kill his soul but can’t. Is there any truth in that as a description of Ian Fleming?

Germaine’s point about Macbeth is a lovely one. I am a huge fan of hers, incidentally: I wrote part of my first novel, The Vision of Elena Silves, at her house near Cortona in Tuscany, and telephoned her not long ago at a nursing home in Queensland. But it’s not, I think, so applicable to Fleming, whose solitary soul was exhilarated by golf, travel, bridge and scuba-diving. A more obvious parallel is with Frankenstein. “I have created a monster,” Fleming said in 1961. “I have written every permutation of sex and sadism, and still the public wants more? What shall I write about?”

Why did you avoid anything but a nominal reference to Roger Moore, the actor who replaced Connery as Bond?

I made a decision to stop in 1964 when Fleming died; nothing against Roger Moore, but for reasons of length. It’s already 704 pages – and that’s after I spent two months in Tasmania cutting 50,000 words.

In the final depiction of Fleming, your writing takes on a tragic quality I don’t think I have ever encountered in a biography. Were you conscious of the material calling out to you to be treated with a sort of conscious grandeur through all the devastation and bodily depredation?

I’m grateful that you feel this. The material was both over-familiar and strong meat. I tried to approach it as if discovering for the first time the epic horror of what he faced. I’m not a golfer, but his evident love for the game and ultimate ambition to be Captain of the Royal St George contained a genuine truth about him, a modesty, a love of tradition, male companionship, the outdoors etc, that had less to do with competitive sport (he was no great golfer, evidently) than with the greater game played out on life’s fairway.

Ian’s son, Caspar Fleming (who died by suicide aged just 23, in 1975) had his father’s brilliance and to the highest degree his fragility. Why did you end with Caspar?

I felt that Caspar’s sad history says a huge amount about his parents, who both struggled themselves. In particular, he reveals Ian Fleming’s fundamental weakness under all the flamboyance: one wounded child creating another.

To writing more generally: As a boy, 50 years ago, you read aloud to Jorge Luis Borges … What in particular did you read to him? Did he ever read James Bond?

It has been 50 years since I climbed the stairs to Borges’s dark apartment in Avenida Maipu as a twerpish 16-year-old to ask if he’d contribute a poem to my school magazine. I read him then an Anglo-Saxon fragment that I don’t remember; also, Kipling’s poem Harp Song of the Dane Women and a passage from Hamlet. Borges asked if I would pick out from his glass-fronted cabinet the complete works of Shakespeare. He wished me to check a quote. Borges remembered the line as: “There’s nothing good or bad but thinking makes it so.” Shakespeare had in fact written: “There’s nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.” Borges contemplated the extra word and said. “My version is better. Memory has made it better.” One could also say that a failure of memory had made it better. Borges had improved the sentence by forgetting a superfluous, inconvenient, unrhythmical word.

An impossible question I know but who do you think of as the greatest or the greater of the old towering modernists?

This is not to ingratiate myself with Australian readers, but I consider Patrick White a colossus. I remember walking along Dolphin Sands in Tasmania with Tom Keneally, a friendlier giant, having discovered White somewhat late-ish. Tom said with typical generosity that on his day White was better than Faulkner. After a lot of hectoring, I managed to persuade the Everyman press to republish Voss. Recently, the painting that White hung above his desk while writing that novel has appeared on the wall of my local pub in Wiltshire. White had left it to his UK publisher (and Fleming’s), Tom Maschler, who gave it to his son Ben, who then bought the pub. I glance at it every time I have a pint of Butcombe (beer) at the Compasses, to remind me of Australia. Covid meant we couldn’t go to Tasmania for two years. I’ve been back twice in the last six months, to cut and polish Fleming, and I will take my family there at Christmas. My Icelandic-Canadian wife is a children’s book writer and illustrator who illustrated Tom Keneally’s children’s book Roos in Shoes. My youngest son was born in Hobart and has an Australian passport, lucky bugger, and is going to study art in Sydney next year. I love it more than any place on earth and hanker to spend more time there. Hopefully, now that I’ve completed Ian Fleming, I can.

Ian Fleming: The Complete Man by Nicholas Shakespeare (Penguin Random House) is published this week.