Ezra Pound by David Moody: mad north-north-west

Ezra Pound was convicted of treason and confined to a ‘monkey cage’. He also transformed poetry. Was it worth it?

Ezra Pound, an American born in 1885, can be considered the inventor of modern poetry in English. He was also the most notorious literary figure of his time, whose country sought to execute him.

Pound’s father worked as an official at the Philadelphia Mint, and Ezra was a self-confident only child. After trips to Europe with an aunt, he decided, while still at school, to associate himself with the high culture he found there, as the novelist Henry James was doing. His father agreed to him abandoning the start of an academic career and going to London to meet the greatest poet of the time, WB Yeats.

Pound was a born pedagogue, irresistibly drawn to teaching. He supported himself in London with lectures and literary journalism, and realised there the necessity of a culture renewing itself. ‘‘Everything has to change, so that everything can stay the same,’’ as the novelist Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa said.

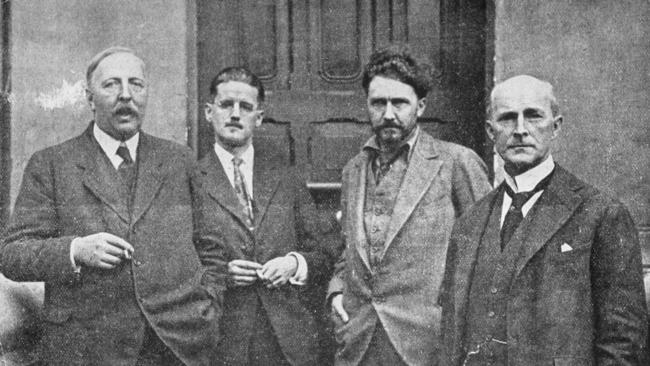

But Pound was too flamboyant to co-exist with the English for long. He had cultivated anyone there he thought an innovative artist, almost all of them expatriates. He promoted James Joyce, revised TS Eliot, toughened Yeats, announced the achievement of his former girlfriend Hilda “HD” Doolittle, maintained a combative friendship with William Carlos Williams back in America, praised Robert Frost on the appearance of his work in England, and encouraged the novelist and painter Wyndham Lewis, among many others, including musicians and in particular sculptors. While raising funds to help some of them, he lived in near penury himself (although he had married into the English upper middle class).

The turning point for what had been his own affectedly archaising verse came when the widow of an orientalist brought him her husband’s transliterations of some Chinese poems. Although he knew nothing of the language, Pound saw that this austere work (even more direct and concrete in translation) was an antidote to Victorian claustrophobia. He produced free-verse versions from these notes, which, with due acknowledgment, appeared as a two-shilling pamphlet, Cathay. It has been called the most beautiful poetry of the 20th century.

A further oriental influence on Pound came via France, where poets had discovered the haiku as part of a fashion for Japanese aesthetics. Pound also saw, at this time, the virtue of the classical Greek epigram, and advocated a similar hardness, clarity, brevity and directness. This confluence of styles, the oriental and the Greek, can be found in his early book Lustra. He called the method imagism, since the oriental component was preoccupied with evoking mental pictures. A longer poem, he saw, could be made by juxtaposing images without comment. (One might also see here the influence of cinema, with its montage technique. Pound would have known the work of the great Sergei Eisenstein.)

The most famous imagist poem (from what became a school) is, appropriately, by Pound. It is realised mainly through implication:

In a Station of the Metro

The apparition of these faces in the crowd,

Petals on a wet, black bough.

The title serves as the first line of the poem. It was written in 1912 when, one realises, underground railway tunnels were lined with soot and the steam there dripped wetness. He sees beautiful, delicate faces among the Parisian women on the platform, who are in black, also. Influenced as he is by Japanese art, he thinks they are like cherry blossoms clustered along a bough — like an exotic vision. The experience has been transformed.

Pound claimed it was better to produce one great image than voluminous works.

He soon incorporated with the somewhat reductive imagist method a more dynamic style he called vorticism, which used the page as a field and deployed dislocated lines across it, simulating energy. The stepped-down line, which was to become so characteristic of his work, indicates a modulation in the tone of voice of the speaker or reader.

This typographical scoring was influenced by the Italian futurist movement, a group of poets surrounded mostly by painters, who favoured aggression in art and called for speed (a racing car was ‘‘more beautiful than the Winged Victory of Samothrace’’), stridency, war, and the destruction of the museums. Pound helped edit an English magazine, Blast, dedicated to these ends.

With amazing obtuseness, he was involved in this as World War I began destroying far more successfully than the futurists could the oppressive monuments of Western culture. When a gifted young friend was killed in the trenches, reality broke in on Pound and he became thereafter anti-war.

With the end of hostilities, Pound decided he must leave England. The climate was ‘‘unsensuous’’ and the English art world slow to listen to him. For their part, they found him, with his cloak and cane, his pile of red hair and his jutting goatee, aggressive. He ‘‘spoke too loudly’’ for them.

He said of himself that he was ‘‘rambunctious’’. With his wife Dorothy he moved to Rapallo, a coastal town in Italy, and acquired a mistress, the violinist Olga Rudge. From there he kept up an immense correspondence.

Pound had already started to write a poem that he planned would be of epic length. At the same time he discovered the social credit economic system, which promised to make culture flourish and put an end to war.

Right economics became the main theme of his writing from then on.

Social credit is opposed to charging interest on loans (usury), which ought to be made by a government agency. It holds that the true purpose of economic activity is not profit but production balanced by consumption. The Cantos, as the work on this unlikely subject is called, runs to 815 pages in its American edition. Most of the poems are several pages in length, and while mainly in English are on occasion thickly strewn with tags from six other languages, including Chinese and classical Greek.

Equipped with this panacea that would end economic strife, Pound corresponded with American senators, wrote political tracts, tried to meet Franklin D. Roosevelt, and had an audience with Benito Mussolini, whom he found to be already sympathetic to ideas associated with social credit.

Talk of the banks at that time and, it seems, anti-Semitism inevitably enters the room. Pound was a dedicated anti-Semite, on The Protocols of the Elders of Zion level. Towards the end of his life he said that violent language, such as he had used against the Jews, was among his great mistakes.

Each of the Cantos typically contains three strands, in no particular order: historical material on opponents of usury, mostly medieval and early American; recounted incidents from classical mythology, to raise the tone; and anecdotes about writers, artists and ‘‘characters’’ he had known in England, whose ‘‘asperities’’ diverted him ‘‘in my green time’’, their talk rendered phonetically and often very funny.

During World War II, Pound was foolish enough to make broadcasts for the Fascist government of Italy when American troops were already in the country. One can’t imagine he was a particularly effective propagandist: he was not directed what to say, so he gave a talk, for instance, on the poetry of ee cummings, with a smattering of social credit thrown in. He was arrested by the Americans and kept for almost a month in an open-air cage, in freezing conditions, with searchlights trained on him at night.

Returned to the US, he was charged with the capital crime of treason. The defence contrived by his lawyers was that he was ‘‘incompetent’’ to stand trial; psychiatrists testified that he had probably been insane for many years. He loudly claimed to know more about economics than anyone else in the world. It was considered ill-advised that he speak in his defence.

Pound spent 13 years in a hospital for the criminally insane in Washington, DC, without trial, but with the death penalty always a possibility. While his case was still controversial he was awarded the Bollingen Prize, for the best new book of poetry, by a jury of his peers. His beliefs were held by a majority of the adjudicators to be irrelevant in appreciating the excellence of his writing.

Arthur Miller, Saul Bellow and others wanted to have him shot (the Nazi death camps had been revealed on film). The poet and playwright Archibald Macleish, who had served in the Roosevelt administration, was moved by his situation and worked hard and long to have him released. Pound was ungrateful, perhaps because of the association with the “Jewish” president. Frost, although not an admirer of Pound or of his work, used his influence among Republicans. Pound’s comment was that Frost had not been in a hurry.

On his release, Pound went back to Italy with his wife and a young disciple, his secretary. He wanted to marry this woman, but Dorothy Pound was his court-appointed guardian and had control of his monetary affairs. She had spent 13 years in a basement room to be near him, but now the atmosphere between them b came ‘‘poisonous’’. Eventually, the secretary resigned. She didn’t like Italy, she said, and preferred Texas, where she came from. For the rest of her life she refused to be interviewed. Pound moved back in with Rudge, his previously estranged mistress. Dorothy moved to England in 1961, where she died in 1973.

Pound and Rudge lived in Venice, and he sank into silence with visitors, saying only that he had nothing to say. One might guess he suffered from dementia. He still managed to attend readings and festivals across Europe with Olga, and was interviewed by French TV, saying nothing. He died in 1972 and is buried on an island opposite St Mark’s in Venice.

Pound is the most divisive of poets. He is awarded the largest representation in the Library of America’s anthology American Poetry: The Twentieth Century, but in recent years has been somewhat devalued by followers of Wallace Stevens. The two figures seem incompatible, to the followers of either. Pound will remain problematic. There is no need to try to resolve this.

A. David Moody’s three-volume Ezra Pound: Poet is the fifth biography of Pound since his death in 1972. Seeing its three sturdy volumes, I was afraid it would belong to the modern school of computer-generated ‘‘Life’’ that sacrifices readability to the accumulation of facts (some of which might be stored in the archives, in the unlikely event that they might be needed at some point).

But it must be said for this dossier that it is compiled with immense competence and lucidity. If it is not the biography as work of art, it is all one could ask for as information; and it rises in the third volume to the condition of high drama.

What do we know of Pound? He was remorseful, which judges like to see. He said he had ‘‘always bungled’’. He was principled: he refused to accept any aid in his release from the ‘‘bug house’’ if it didn’t recognise his constitutional right to free speech. Many of his disciples were segregationists and anti-Semites, whom he used to have his works kept in print and his ideas disseminated.

He was kind to the other inmates in the ‘‘hell hole’’ they shared, but condescending and arrogant to the doctors. He praised Hitler: ‘‘Fresh meat on the Russian steppes’’ was his chortling remark on the news of the German invasion of the Soviet Union. He never had a day’s physical illness, and had an IQ ‘‘somewhere over 120’’. He was callous to the loyal women in his life, cutting off his wife and his son by her, and letting his aged mistress return across the Atlantic by cargo ship, on the day after she had arrived in the US, when she discovered his affair with a young painter and heroin addict.

If extreme egotism and grandiosity are symptomatic of madness, he was rightly diagnosed by the five or six doctors who attended him. He seems to have been mad ‘‘north-north-west’’, in Shakespeare’s phrase. What he did have, an experience of which he induces in his reader, was a bad case of attention deficit disorder, so unstable, so jumpy and momentary, is the surface of his work. At times, he reduced his poems to jottings, to memo-notes, so that he could cover all of his reading.

My favourite of The Cantos is XLIX, which begins:

For the seven lakes, and by no man these verses.

Rain; empty river; a voyage.

Fire from frozen cloud, heavy rain in the twilight.

Under the cabin roof was one lantern.

The reeds are heavy; bent;

And the bamboos speak as if weeping.

Generally, the late personal Cantos are the best (with the great exception of Canto 1) — his ‘‘Pisan Cantos’’ (numbers LXXIV to LXXXIV), about the humility that came upon him while in the ‘‘monkey cage’’. There is also the moving summation of Canto 116, and the fragments that follow it. Homage to Sextus Propertius, from his middle period, has a sense of play and marvellous rhythms. Add Lustra and Cathay to these and we have a magnificent, though not extensive, body of work. But how expensive was the temperament that brought it.

Robert Gray is a poet. His most recent collection is Cumulus: Collected Poems.

Ezra Pound: Poet

By A. David Moody

Volume 1: The Young Genius 1885-1920, 528pp, $60.95 (HB), $35 (PB)

Volume 2: The Epic Years 1921-1939, 440pp, $60.95 (HB)

Volume 3: The Tragic Years 1939-1972, 680pp, $60.95 (HB)

Oxford University Press