Ending the ‘whitewash’ of Australia’s convict history

There’s something jarring about this 20-page list of black convicts. It’s not the origin of the convicts, nor is it their sentences. It’s the names that jump out at me.

There’s something jarring about the 20-page list of black convicts at the end of Santilla Chingaipe’s book. It’s not the origin of the convicts (though most come not from the British Isles but from Barbados, Jamaica and other British colonies in the West Indies). Nor is it the sentences, the standard terms of seven years, 14 years or life. Sprinkled among the usual crimes (“housebreaking”, “highway robbery”, “stealing cucumbers from a garden”) are some less familiar ones: “beastliness”, “desertion”, “absconding”. It’s the names, however, that jump out at me: Castor, Christmas, Felix #1, Romeo, Peggy. Names like these were given not by parents to their children, but by owners to their slaves.

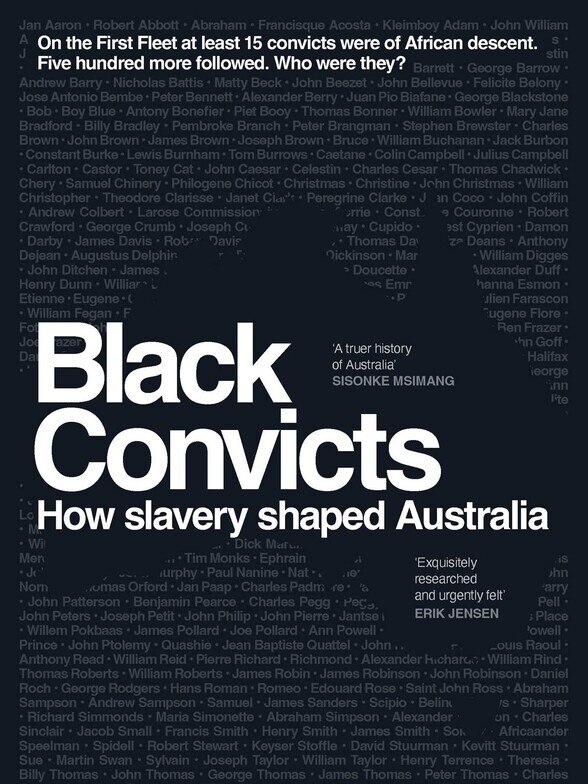

Of the roughly 760 convicts who arrived in Sydney in 1788 on the First Fleet, at least 15 were black. Between 1788 and 1842, about 80,000 male and female convicts were transported to NSW, of whom as many as 500 were of African descent.

Chingaipe argues that these black convicts have been “whitewashed” from Australian history. They are certainly missing from the Museums of History NSW website, which informs visitors that “almost two-thirds of convicts were English (along with a small number of Scottish and Welsh), with the Irish making up the remaining one third”.

Colonial archives and old newspapers however, are surprisingly rich in material about black convicts, but uncovering this material sometimes involves reading between the lines. Blackness itself often has to be inferred from euphemistic references to “dusky” complexions or “woolly” hair.

Chingaipe’s book aims to save Australia’s black convicts (most but not all of them former slaves) from what she calls “archival oblivion” – a state of being present in the historical record but absent from popular history.

Drawing on rigorous archival research in Africa, the US, the West Indies and Australia, she vividly brings to life dozens of extraordinary characters: people like John Moseley, born into slavery in Virginia, who fought on the British side in the American War of Independence and was transported to NSW on the First Fleet; and Maria Middleton, a 17-year-old enslaved girl from British Honduras (now Belize), who killed a man who was trying to rape her and was transported for life to Van Diemen’s Land. The convict records listed her only as “Maria (a slave)”. After marrying a free black man who worked as a whaler, Maria was required to supervise a white female convict – a switch of roles that amused one Hobart newspaper, which noted that in Maria’s case “the common order of slavery was reversed”.

But, as her subtitle suggests, Chingaipe’s purpose is not just to illuminate the lives of Australia’s black convicts. She wants us to see the story of black convicts in Australia as part of the larger and more shameful history of black slavery, and their omission from the popular narrative of Australian colonial settlement as symptomatic of a wider obfuscation about British involvement in the slave trade.

Between 1640 and 1807, when the British parliament passed the Slave Trade Act, Britain is estimated to have transported as many as 3.5 million African slaves. The 1807 Act banned the buying and selling of slaves throughout the British Empire, but the ownership of slaves continued until 1838.

The first decades of the convict system in Australia coincided with the last decades of the slave trade, and Chingaipe is at pains to show how the two intersected. A convict named Alexander Simpson, for example, was one of several black men transported to Van Diemen’s Land for their involvement in slave rebellions in Britain’s immensely lucrative West Indian sugar plantations. The last of these, the so-called Baptist War in Jamaica in 1831–32, became the largest slave revolt in the British Empire. On his arrival in Hobart, Simpson told authorities he had been “exciting the slaves to rebellion”.

Chingaipe shows how the convict system co-opted not just enslaved individuals but the machinery of slavery. Former slaves ended up as convicts; ships used in the slave trade were later used to transport convicts; crimes committed by slaves could result in transportation; and the shackles and beatings inflicted on convicts were scarcely different to those inflicted on slaves.

But convicts were not slaves, even if some of them had previously been enslaved.

Robert Hughes drew a clear distinction between the two in The Fatal Shore: “The master owns the slave: his work, his time, his person. Slaves are bought and sold, they are property. Their rights begin and end with their status as chattels … None of these conditions applied to the convicts Britain exiled to Australia. Each served a fixed term of punishment and then became free. None was a chattel, the property of a master. All of them, within limits, had the right to sell some portion of their labour on the free market … Their masters did not have the right to flog them; such punishments could only be inflicted by the sentence of a magistrate … Their children were born free.”

While Chingaipe acknowledges that the two systems were not the same, she treats them as analogous, stating that both “begin with people being coerced onto ships, and end with workers in regions that need cheap labour to fuel economic growth”. Insisting that the analogy between the two is “clear”, she draws attention to common terminology (“gang”, “master” etc) and to the “cruel continuity” of punishments.

While her research proves that hundreds of black men and women (a tiny proportion of the total convict population) escaped slavery only to become convicts, I can’t see how this adds up to slavery having “shaped Australia”, as the book’s subtitle asserts. Chingaipe writes that she has tried to “restore some sense of humanity to the Black convicts by making their presence visible” and to scotch the “falsehood that convicts were all white and British”. Her book succeeds admirably on both counts, even if its polemic feels a bit overblown.

Tom Gilling’s most recent book was The Diggers of Kapyong

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout