Echoes of self in ‘story of a lifetime

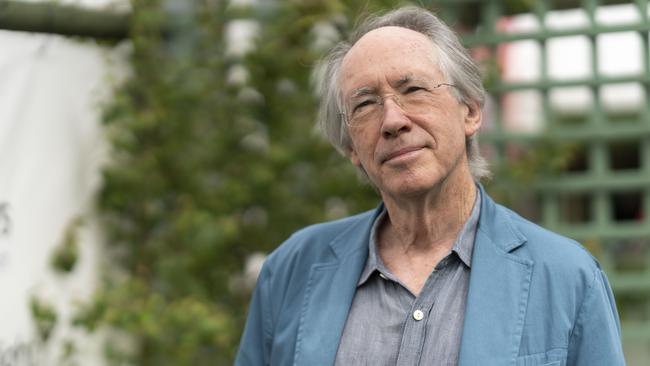

Ian McEwan’s 16th novel is billed as ‘The story of a lifetime’. Perhaps it is therefore no surprise that, at almost 500 pages, it is by far his longest work of fiction.

Ian McEwan’s 16th novel, Lessons, is billed as “The story of a lifetime”. Perhaps it is therefore no surprise that, at almost 500 pages, it is by far his longest work of fiction. Amsterdam, for which he won the 1998 Booker Prize, clocks in at 192.

The lifetime in question is that of Roland Baines: minor poet, occasional journalist, suburban tennis coach and hotel dining room pianist. His lack of literary success separates him from the author but in other senses he is autobiographical.

His father is in the British army – as was McEwan’s – rising to the rank of major. His postings take the family to decidedly non-English climes, including Libya, as did Major McEwan’s.

The timeline moves from 1959, when Roland’s family returns to London and he becomes “another inky boy in a boarding school”, to 2021, when he is in his early 70s, as is the author.

The most striking similarity – particularly because of the difference between what happened in life and what happens in the pages – comes earlier. It involves Roland, his wife Alissa and the care of their son Lawrence. I will not be surprised if this autobiographical aspect becomes a talking point.While a man – Roland Baines – is the ostensible centre of this lifetime, he is almost a secondary character. More than anything else, this is a novel about unconventional women. Whether what they do is right or wrong or somewhere in between is for readers to decide.

The first is Roland’s piano teacher, Miriam Cornell, who he meets when he is 11. By the time he is 14 their relationship has moved beyond the keyboard. “Now he felt like a god.”

Decades later there is a remarkable moment where the adult Roland tracks down Miss Cornell. “You happened to meet the right person for you when you were eleven,’’ she tells him. “You were far too young to know it, but I did. … I wanted you as much as you wanted me. I had plans for us.”

This is provocative at a time when historical sexual abuse is in the headlines. When Miss Cornell and Roland begin their lessons, he is a fair bit younger than Dustin Hoffman is in The Graduate.

I will not reveal what happens but it is a complex emotional story, on both sides. In the acknowledgments McEwan thanks his English teacher, “the late Neil Clayton, who insisted I use his name unchanged”, and adds “No such piano teacher as Miriam Cornell was ever’’ at his boarding school.

The second unconventional woman is Roland’s wife Alissa, who wants to be a writer worthy of the Nobel prize. The novel opens with her “vanishing”. Roland is 37 and Lawrence is a baby.

Alissa has not vanished as in the horror movie of that name, but up and left. She sends postcards, first from Dover, then from continental Europe.

When a detective inspector comes by and asks some gentle questions, Roland is silent, lost in thought. “The self-made hell was an interesting construct. Nobody escaped making one, at least one, in a lifetime. Some lives were nothing but.”

Again I will not reveal what happens between Roland, Alissa and their son, or to Alissa’s literary ambition, except to add that, as with Miss Cornell, it is not simple, clear-cut or fully understandable. “It was all one lesson,” Roland thinks at one point.

McEwan draws from a few writerly wells. Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Hardwick are comparison points for Roland and Alissa. He also has some fun, with a friend of Roland’s mentioning the “timid time-serving mediocrities” who win the Booker.

There is an extended scene between Roland and Alissa, towards the end, that is a writing masterclass, as is one between adult Roland and Miss Cornell.

While there are numerous other characters in this book, I think it is best summed up as one lifetime, three people: Roland, Alissa, Miss Cornell.

“ … the lifelong mystery of Alissa was at the very least always interesting. There was no one remotely like her in his life. Miriam apart, no one so extreme.’’

This novel’s time sweep takes in world-changing events, from the Cuban missile crisis and fall of the Berlin Wall to Chernobyl and Covid. McEwan reminds us that history repeats.

“He did not see how the Russians could afford to back down when the whole world was watching.” That’s in 1962 but could be written today. And, a couple of decades later, Roland walks past people holding “Rushdie must die” placards.

We read novels in a personal way. I think the first third or so of this one is intriguing in concept but slow in execution. However, once Roland hits his mid-50s, I feel for this fellow traveller, especially as he balances “the weight of the near future”.

With that in mind, I’ll finish with fiftysomething Roland pondering what Raymond Carver might call a small good thing. “Was it too late to become a better and bigger person?” There is a willing self-interrogation and unexpected generosity in this novel that suggests it is not.

Stephen Romei is a cultural critic, with a special interest in films and literature.

Lessons