Dorothy Parker’s sharp tongue and a restless spirit

When Dorothy Parker took her razor wit to California and the movie industry, she brought her troubles, and ideals, along.

Dorothy Parker was one of the great transients of American literary history, yet she remains more permanent than most writers of her era. She wrote fleetingly, much of her work still pungent a century later: light verse and epigrams, stories and soliloquies, brief reviews, snippets of snappy film dialogue. A restless spirit, she dwelled mostly in hotels, and is most often linked with the Algonquin on West 44th Street in Manhattan. There she traded insults throughout the 1920s with a lunchtime assembly of smart alecs known variously as the Round Table and the Vicious Circle.

In those years Parker was young, fearless and the wittiest of the group, even if many of her alleged wisecracks were invented by bored reporters desperate for copy. The Algonquin made a character out of Dorothy Parker, often copied but seldom matched: the petite, sexy brunette with an aura of mischief and a mouth full of razors. Beneath the legend lived a complex, deeply unsettled person with serious literary chops, trapped in an internal battle between the will to write and the wish to self-destruct.

At least four full-length biographies of Parker have been published, along with a number of affecting shorter portraits by fellow writers who knew her well, particularly Edmund Wilson, Lillian Hellman and Wyatt Cooper (father of Anderson), whose unparalleled Esquire magazine profile from 1968 is titled Whatever You Think Dorothy Parker Was Like, She Wasn’t. Cooper and Parker became friends in Los Angeles in the early 1960s, when they both worked as screenwriters on the Fox lot and lived near each other. Parker always insisted that she hated Hollywood. Yet she spent nearly half her life there, off and on, an often underplayed fact about a figure so firmly connected in the public imagination to New York.

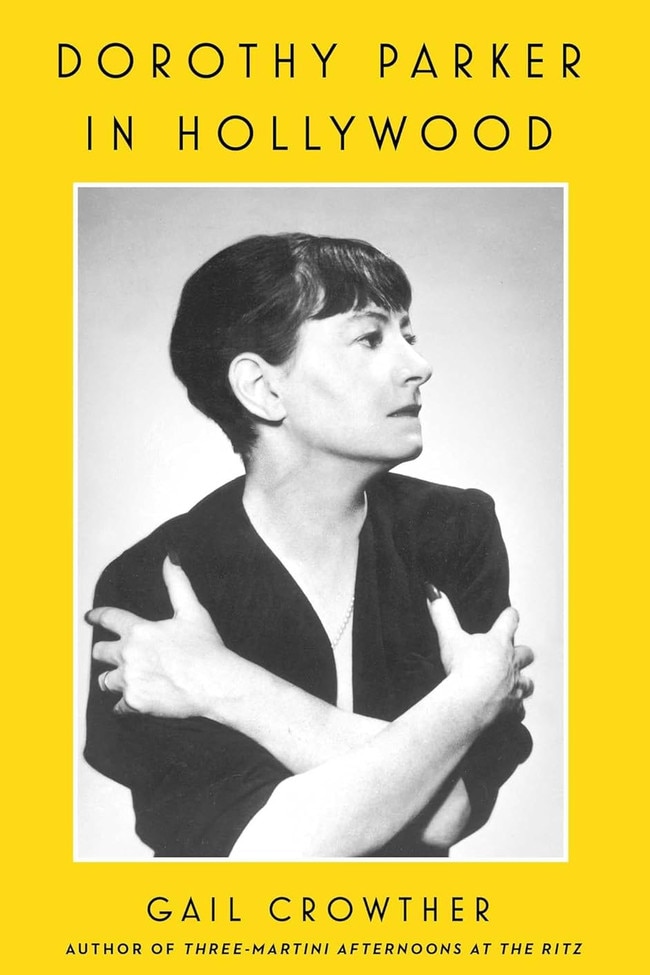

That makes Gail Crowther’s Dorothy Parker in Hollywood a welcome effort to expand our view of the writer’s career. The film industry’s influence on Parker, as well as hers on it, is a juicy subject that’s ripe for evaluation in our own screen-obsessed age. Crowther is the author of Three-Martini Afternoons at the Ritz (2021), a brisk dual narrative about the midcentury American poets Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton. Her new work is similarly efficient, neatly synthesising all the available research in the absence of any new information.

Parker was in her mid-30s when she first arrived in Hollywood. She had already weathered an early marriage and divorce, some bad love affairs, an abortion, two suicide attempts (at least two more would follow) and a growing addiction to alcohol. She was also a near-instant literary success, with two best-selling collections of poetry, an O. Henry Prize for her short story Big Blonde, and high-profile magazine stints as a drama critic and a book reviewer. Hollywood was paying attention. Having abandoned silent movies for talkies, the studio chiefs were looking for east coast writers fluent in quick-fire dialogue. MGM executives poured on the flattery and offered Parker a weekly salary of $300 (about $4700 today, by Crowther’s calculations). Needing the money, she accepted their three-month contract in early 1929 and headed west. She spent her days alone and ignored in her empty Culver City office and fled as soon as she could, insisting that MGM’s head of production, Irving Thalberg, pay for her train fare back home.

Parker’s second Hollywood sojourn was more successful, because she arrived this time with backup. It was 1934 and she was newly married to Alan Campbell, an actor and writer 11 years her junior who looked like a deluxe younger version of her good friend Scott Fitzgerald. Campbell was affable and capable, ready to do what she could not: structure a film treatment, cook them a meal, organise their finances and curb some of Parker’s self-harming impulses, leaving her free to reel out the lucrative one-liners.

Flitting among studios, the Parker-Campbells worked assiduously and often uncredited on films throughout the 1930s – at least four in 1935 alone. In 1937 they earned an Oscar nomination for writing on David O. Selznick’s A Star Is Born, which sent their prestige and their income soaring. (In 1948 Parker was again a nominee, without Campbell, for her work on Universal’s Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman.) With their grand combined salary – as much as $5000 weekly as the Great Depression slogged on – they bought expensive houses in Beverly Hills and Bucks County, Pennsylvania, making a bid for stability.

As Crowther points out, it’s difficult to trace Parker’s specific contributions to the 18 film scripts she worked on. But the author makes some good guesses, spotting “Parkeresque quips with a more serious message underneath” in A Star Is Born and detecting aspects of Parker’s experience as a woman with alcoholism in Smash-Up. For Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942), Parker tried, she told an interviewer, “to give the girl more to do”.

Parker gave a big portion of her earnings to political groups. She was ardently voluble about every cause célèbre, from the trials of Sacco and Vanzetti and the Scottsboro Boys to the Loyalist efforts in the Spanish Civil War. She joined more than 30 organisations in the 1930s, hosted their fundraisers and donated lavishly. Many of those groups, including the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, which Parker co-founded in 1936, were later accused by Martin Dies, the chairman of the House un-American activities committee, of being communist fronts. She helped establish and drive attendance toward the newly formed Screen Writers Guild, also suspected by HUAC of communist infiltration.

There is no reliable evidence that Parker was a member of the Communist Party, but she was as sympathetic as it was possible to be. She was guilelessly convinced that it was on the right side of history. Also important to her was the sense of belonging that the party offered. Here was a chance to heal the wounds of her lonely childhood and an adulthood hounded by depression, which she tried and failed to medicate with alcohol. The film colony’s left-wing community represented home to Parker. Even when her life fell apart in the late 1940s, her marriage imploding and her livelihood threatened by insinuation during the HUAC investigations of the movie industry, her houses sold and her future uncertain, she still had some film work and like-minded friends in Hollywood. When she left for the last time, after Campbell’s death from a Seconal overdose in 1963, she lived for only three more years, dying of a heart attack in a grimy room at the Volney Hotel in Manhattan at the age of 73.

“It is time to take a fresh look at Parker and encompass the fullness of her achievements,” Crowther writes in the book’s epilogue. She deserves much credit for identifying Parker’s Hollywood years as a valuable subject. But she ventures no further than the threshold of assessment, offering only that Parker “paid the price for somehow never quite fitting into her time”. Really? Parker is pinned to her era like a moth on a board, as a figure all but epitomising the idealism and anxieties of her American moment. Other vital questions that get only cursory attention offer invitations for future scholarship. Why does Parker continue to endure as an object of fascination? How best to appraise her film work in relation to her poems, stories, criticism? Was Parker wasting her abilities in Hollywood, as she herself believed, or is it possible that screenwriting was the apotheosis of her highly concentrated talent?

“Brevity is the soul of lingerie,” Parker famously observed. But of biography, not so much.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout