Don Watson on the warpath against Worst Words

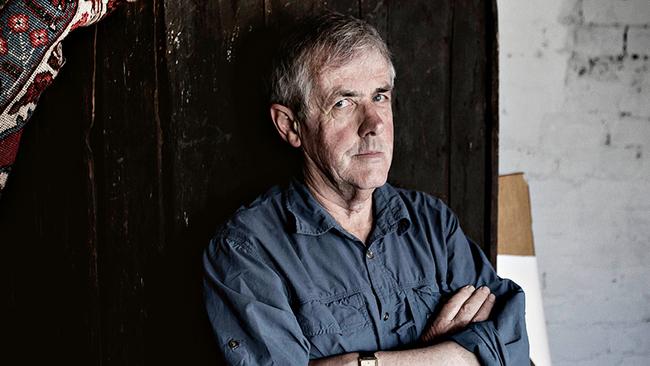

Paul Keating’s former speechwriter has again taken up cudgels against cruelty to the English language.

Driving to work the day after the Melbourne Cup, won in historic fashion by local jockey Michelle Payne on the 100-1 pop Prince of Penzance, I heard a lot of radio chatter about chauvinism in the racing game. What sort of chauvinism, I wondered. Victorian chauvinism, perhaps? Like Kingsley Amis, I am a beer chauvinist, at the races and elsewhere, as I believe it superior to all other drinks. Of course I know the discussion was about male chauvinism, but it irks me that it seems to be the only kind we have nowadays.

So it was that on arrival at the office I fell upon Don Watson’s new book, Worst Words: A Compendium of Contemporary Cant, Gibberish and Jargon (Vintage, 439pp, $29.99). I didn’t locate an entry for chauvinism — as the subtitle suggests, this is not a (mis)usage guide — but I did find much to enjoy. Watson, former speechwriter to Paul Keating and acclaimed author, has compiled an A-Z anthology of the jargon that passes for everyday language in the modern world, especially in politics, business, bureaucracy and, most sadly, education.

You know the sort of words and phrases he means: action plan; change agent; drill down; going forward(s); future directions; impact; key indicators; lifestyle outcomes; road map; thought leader; unpack; vision statement and hundreds more. Here’s a few in one sentence he cites: “In the recent evaluation by the Australian Council for Educational Research, school and community members reported that Direct Instruction was having a positive impact on student outcomes, but the researchers were not yet able to say whether or not the initiative has had an impact on student learning.” Watson remarks: “Read it five times and you will not find a sensible meaning. Not even if you drill down, deep dive or unpack it.

Watson’s approach is to list a jargon word or phrase, provide a definition and an example of its use. He also has some fun modernising well-known passages, as in: “I love a sunburnt lifestyle / a land of sweeping plains”; “Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art though, going forwards, Romeo?”; Lady Macbeth’s call to “unsex me here, / And fill me from the crown to the toe topful / Of direst goal setting’’; or presenting Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnet “How do I love thee?” in bullet points.

His discussion of Winston Churchill’s “We shall fight on the beaches” speech might stand as a primer for the book as a whole. “No mention of strategy,” he writes. “No action plan and nothing to be actioned. No enablers. No risk management. No accountability. No outcomes to be ‘passionate’ about. No ‘Leadership is about making the right decisions for our country’s future’. No ‘That’s what the government is working to deliver for you’.” He returns to Churchill in the entry for the verb “attrit” (“From attrition — wearing down’’): “We shall attrit on the beaches, we shall attrit on the landing grounds” and so on.

OK, so management jargon delivers a sub-optimal consumer outcome for language lovers, but is there a deeper adverse impact, if we drill down a bit? Watson thinks so. “We adapt to the new all-purpose words and forget the many old ones they’ve replaced. With their passing, meaning fades; poetry and other keys to human possibility, including irony and critical self-reflection, are lost.” The result is “a realm of lost knowledge, of assured ignorance’’.

To finish with two favourites, if that’s the right word: author as a verb — “The authoring’s on the wall”; “It’s authored all over your face” — and “zero kilojoule hydration option” (ie water), attributed to the head of the Australian Bottled Water Institute. As Watson alludes, how poorer would we be if that phrase had been available to Coleridge: “Zero kilojoule hydration options everywhere, nor any drop to drink.” Just thinking about it makes me feel like actioning — indeed fast-tracking — a couple of high-kilojoule hops-flavoured beverage options.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout