Documentary Keating: The Interviews reveals former PM's killer instinct

A TELEVISION biography of Paul Keating offers a revealing portrait of the loved and loathed former prime minister.

'I WAS in for the game of it," Paul Keating says at the start of an intriguing new four-part series which, like the best television, leaves us with more questions than answers.

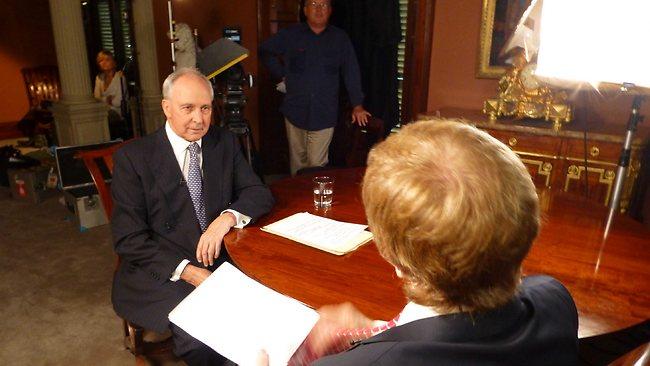

Through face-to-face interviews, artfully selected archival footage and photographs obviously chosen from the former prime minister's personal collection, Kerry O'Brien provides an absorbing TV biography of one of our most argumentative leaders.

"You can see the appeal in the personality, the nature of the man, his capacity to draw and to polarise, and his facility to tell stories," says O'Brien, who is executive producer of Keating: The Interviews, along with Ben Hawke.

Like or loathe the acerbic Keating, the Mahler-loving Bankstown bodgie, who will turn 70 in January, is a card-carrying one-off, a true political original. "One of the fascinating things for me is that he is a serious thinker," O'Brien says. "Philosophy switches him on. Whether his conclusions are the right ones is another matter."

In politics, Keating often appeared manipulative and cruel, nourished by intrigue and the admiration of a bitter freemasonry led by Labor warriors such as Graham Richardson.

"Having enemies worries some people; for me it's a badge of honour," Keating says in the interviews, with a slight smile. "It's never worried me that a group of people would never have a bar of me." There are many of those small grimacing smiles and they all mean something slightly different.

O'Brien, the almost silent inquisitor, and his entertainingly voluble subject are sitting in Keating's Sydney office, a palatial drawing room framed by architectural columns, a space of classical proportions full of polished surfaces and expensive collectables. Several cameras catch the exchanges in hovering subjective close-up, a third holding an expansive wide shot, allowing the operators to judiciously alter their focus as both faces tell their stories.

"At Keating's request we spread it over several months because, of course, he had to go back and do his own homework," O'Brien says. "I had a research brief the size of the Domesday Book and he had to freshen up his own memory from his papers and records."

Three extensive interview sessions took place from March to July, about two days of interviews in each of those weeks.

While in recent years Keating has appeared a man of chilly charisma and aristocratic grievance, with O'Brien he is charm personified, all urbanity, suavity and politesse, his seeming modesty just concealing at times the Irish Catholic brawler. But what is so fascinating in the first episode is the way he tells us of the soft moments in his volatile political life, particularly his days as the working-class kid with no formal education, who so fastidiously began a lifelong study of power.

He talks of growing up in Bankstown, once known as Irishtown, in "the land of the fibro house", always beautifully presented by his mother who, along with his grandmother, passed on the killer instinct. "My grandmother and my mother invested a tonne of love in me; it kind of radiates from you and gives you that inner confidence that's almost like wearing the asbestos suit that goes through the fire and you're not going to get burned."

Then there's his friendship with former NSW premier Jack Lang, an ancient, near deaf giant of a man "with telescoping arms" who taught a tyro apparatchik "the use of language, the force of language". The anecdotes pour out about Lang, a walking encyclopedia of political history, who called his young acolyte Mr Keating.

"One of your problems, Mr Keating," Lang told him, "is that you take people at their word; this is a business where duplicity is the order of the day. Look for the best in people, by all means, but keep a sceptical eye peeled for what they are saying to you and what they really mean." (Keating's impersonations are a delight.)

On a sadder note, he says it took a decade to get over the early death of his father, Matt.

"But there is a place for sadness and melancholy; you don't want to be sparkly and happy all the time," Keating says. "You need the inner life, the inner sadness that rounds you out."

We like these imaginatively conceived TV political presentations, part interview, part archival re-creation of what are now almost dream times to so many of us. They rate well, too. There was SBS's important documentary series Liberal Rule in 2009, an epic dramatisation of the story of the transformation of the contemptuously nicknamed "little Johnny Howard" into the feared man of steel.

Earlier this year Paul Clarke's controversial Whitlam: The Power and the Passion propelled us through Gough's quixotic journey with a kaleidoscopic sense of narrative that was quite exhilarating, though Whitlam haters are still finding factual errors. Although Keating is simpler in conception, it's just as entertainingly told, largely in this colourful political storyteller's own words, O'Brien simply guiding him and providing elegant segues.

"It's not an electronic memoir because it is a conversation ... it's a kind of extended profile but it's exploring as much about him as I'm able to," O'Brien says.

He pursues Keating at times and the exchanges crackle; no one lulls and lures while smiling and nodding quite like O'Brien. His admiration for Keating as TV talent is obvious, though it rarely tempers the friendly but perceptive inquisition. Sometimes his subject's wit catches him off guard. Keating is not only a thinker, he is a wonderful talker; his wit is cunning, cutting and often surprising.

Clive James once said TV doesn't mind dead air: "You can stop and think for a while and look like Socrates." And Keating is good with pauses; you can almost see his mind deciding which tack to take next, how far he should go, and whether it's relevant. Or entertaining for that matter; he relishes a joke.

He's an old hand at understanding the difference between easy-seeming eloquence and mere rambling on. He sometimes just pauses in a run, then adds an "and so on" kind of closer, flicking it away with his hands. While he is very candid, there are obviously parts of himself he doesn't want to reveal and O'Brien knows that too, often just a little reluctantly moving on to another subject.

Keating's voice these days is hoarser, more adenoidal, but when he's on a run it rises and falls like a wood chipper chewing up brush. These sprays are delivered with that slight smile, his prominent front teeth glinting.

Some won't like this series just because it's the despised Keating, while others, as usual, will disdain the idea of an approach to history that makes documentary accessible for a mainstream prime-time audience. TV is inimical to intellectual discourse, they say.

But there are quite unforgettable moments here; surely no prime minister has revealed so much about themselves and their Machiavellian craft to the TV cameras.

Keating: The Interviews, Tuesday, 8.30pm, ABC1.