Star Wars, The Simpsons and Marvel: is Disney+ a match for Netflix?

Disney+, the film studio’s streaming service, is here, offering Star Wars, The Simpsons, Marvel films and much more. Will it beat its established rivals?

As media launches go, the recent arrival of television streaming service Disney+ was as big as a family-friendly Death Star appearing in Earth’s orbit. Disney is the second largest media company in the world, and it is aiming to put its streamer in almost every family home in the country with the help of one of the largest back catalogues in Hollywood.

Five years ago that might have been enough, but the streaming market is now so crowded that Disney has spent millions on producing exclusive content, including almost $120m on a Star Wars spin-off series, The Mandalorian.

Star Wars is more like a sports team than a movie franchise. Hardcore fans’ general attitude is a blend of constantly frustrated hope and ill-concealed loathing.

Indeed, American comic Patton Oswalt’s most-shared stand-up routine is At Midnight I Will Kill George Lucas with a Shovel, where he imagines meeting the franchise creator in 1993, ahead of the prequels. As he discovers that his favourite characters, Darth Vader and Boba Fett, appear as little kids who lose their parents and are very sad, he despairs.

When told the Death Star shows up at the end “being built, and Darth Vader is looking at it”, Oswalt screams with the primal rage of the true fan: “I don’t care where the stuff I love comes from! I just love the stuff I love!”

It’s a lesson Jon Favreau bore in mind when writing and directing The Mandalorian, which was released in Australia in November, in tandem with the launch of the streaming service. The series is the first Star Wars project after the nine movies at the heart of the franchise petered out, disappointing many fans. “The foundation of all genre projects is the fans who have been there since the beginning,” he says. “We’re starting with new characters for a new audience, so how do you balance those two things?”

His challenge was to find a replacement for one of the movie’s most popular characters, Boba Fett, who, awkwardly, died in Return of the Jedi.

The solution was to build a space western around a Mandalorian bounty hunter, Din Djarin, who looks just like Fett. Under the helmet is Pedro Pascal (Narcos, Game of Thrones), delivering a murderously efficient killer with a heart of gold. “I was told to watch Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone films,” he says. “The tone is more Empire Strikes Back.” At first sight, Disney+ shouldn’t need this sort of additional firepower. That back catalogue includes every Disney film and TV series, almost every Marvel film and TV series, almost every Pixar film, all the Star Wars films, every episode of The Simpsons and the National Geographic channel. It costs $8.99 a month.

But catalogues gather dust, as is pointed out to me by the Entertainment Strategy Guy, a senior Hollywood executive who blogs anonymously.

“Content ages fast,” he says in a late-night call. “Snow White and Cinderella hold up, and little girls are always going to want to wear that fancy dress. But teenagers? Not so much. So Disney is focusing on Star Wars and the Marvel Cinematic Universe — the latter offering a run of success no one has matched in Hollywood. The movies earn $2.5bn internationally and act as ad campaigns for the service. But making TV shows that match those movies has only been possible in the past couple of years.”

When Lost launched in 2004, he says, its $13m pilot was the most expensive yet made. Prices have since climbed fast. Game of Thrones cost a reported $10m per episode, The Crown $13m. The Mandalorian comes in at a cool $15m per episode, or $120m for the series — roughly the total production cost of The Fellowship of the Ring film.

And that’s just the first of Disney’s new shows. An Obi-Wan Kenobi series is in development, Marvel’s The Falcon and the Winter Soldier series picks up after Avengers: Endgame, and Tom Hiddleston will be in a spin-off Loki series. By connecting the TV material with the films, Disney aims to build an almost inescapable universe of entertainment.

That said, you can spend a lot on a show and get nothing back — $11m per episode didn’t save Baz Luhrmann’s 2016 flop, The Get Down — so it’s surprising yet somehow inevitable that what broke the internet and ensured The Mandalorian was a hit (after its US launch, it is officially the most in-demand show in the world) was the emergence of Baby Yoda, a tiny green ball of cute, from a floating electronic crib at the end of the first episode. It’s no spoiler to say that Din Djarin switches to protecting the little green beastie and sets off to blast the bad guys before you can say: “Named must be your fear before banish it you can.”

The Mandalorian is set five years after Return of the Jedi. The Empire has collapsed thanks to the death of the Emperor — and, according to Zachary Feinstein, an assistant professor at Washington University, St Louis, an inevitable recession caused by the destruction of more than $612 quintillion worth of Death Stars in four years, requiring at least a 20 per cent bailout of the galactic economy.

RELATED: ‘The most addictive show on television’ | Our next guilty TV pleasure

In third place among the fans is Gina Carano as Cara Dune, a former Rebel shock trooper who spent years expressing her grudge against the Empire by killing every stormtrooper she could find. Offered a post-peace desk job, she quit to kick a little game across the galaxy, where she ends up trading blows and quips with Din.

Dune’s popularity is helped by Carano’s real-life record as a mixed martial arts fighter who suffered only one defeat in her four-year career. “I bring something a little different,” she says. “We’re used to seeing women being badasses, but when I’m doing a fight scene, you stop and think, I believe she can really do that. The fans’ reception was the best feeling I’ve had.”

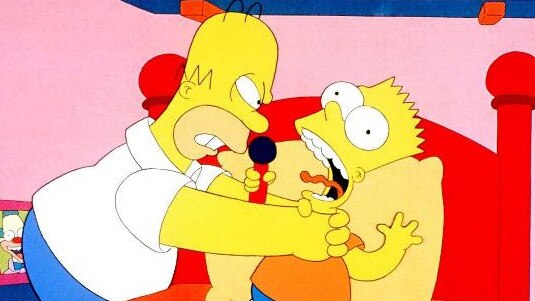

To get here, Disney hasn’t just spent $100m per series on new TV shows. It also dropped $71.3bn on 21st Century Fox — which comes with The Simpsons, Alien, Avatar and Die Hard attached. These will be split between the family-friendly Disney+ and the not-yet-in-Australia Hulu, which Disney plans to roll out internationally. By early April, just five months after its launch (and no doubt aided by people staying home due to the coronavirus pandemic), the streamer had amassed 50 million paid subscribers worldwide.

So is this a Netflix killer, or just more TV, or what’s going on? “The problem with streaming services is that audiences expect every TV show ever made to be available right now, but subscriptions are underpriced,” says Tom Harrington of Enders Analysis.

“Netflix gets around that by borrowing, and Amazon uses it as a loss leader for e-commerce. Disney used to make a lot of money selling shows to other broadcasters, but its businesses with the largest profit margins now are amusement parks, cruises and merchandise. They want to reach massive scale, because if kids watch Frozen 2, they’ll want to go to Disney World and spend hundreds of dollars a day going on the ride or buying the outfits.”

The first Frozen movie, he points out, raked in $1.3bn at the box office in 2013, while Disney’s merchandise and licensing now earns more than $100bn annually.

The information the Disney+ algorithm gives the company will help to decide future films, series and rides. Ricky Strauss, president of content and marketing at Disney+, confirms this. “The collection of data we can exploit across all of our properties is powerful,” he says over the phone from LA.

A similar media merger in the US has produced HBO Max, which is sucking up Friends, Sesame Street, Game of Thrones and Succession (it has no Australian launch date), and newbies such as YouTube TV are trying to get in the game. For now, though, Disney+’s Australian launch has pitted it against Netflix, Amazon, Apple TV+, Google Play as well as ABC’s iview and SBS’s On Demand services. The revolution will not be televised; it will be streamed, and it won’t just be us watching.

“Get to know how people are watching and you can use that to make more money out of them,” Harrington says. “Cinema, DVD, broadcast TV: they gave a rough idea of the audience. But Disney and the others now know who the audience is, what time of day we watch, what we re-watch, how much we earn, what we like. They can leverage that into a movie, TV show or character. Your TV set is like a one-way mirror. We’re watched as we’re watching to make sure we only see the stuff we like.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout