Del Kathryn Barton: The Highway is a Disco

Life and creation are an enormous struggle, but Archibald Prize winner Del Kathryn Barton tells what pushes her on.

There’s an old, rusty cement mixer that Del Kathryn Barton keeps in her studio. Her father bought it second-hand years ago. When it was no longer needed, he left it at home on the NSW south coast until his daughter brought it to Sydney. There it sits today, both out of place and at home; an object from a male domain being introduced by its new owner as a beautiful, feminine piece of sculpture.

Forgotten items, discarded into the world — or found objects, if you’re an artist — are important here. An obsessive collector with an acute eye for fashion, Barton loves thrift shops and jokes that her idea of a good time is to log into eBay with a glass of wine, sifting through the debris of the world.

Which also explains the kitsch ceramic figurines standing to attention in a cabinet near the cement mixer. She wants to collect more, but the plan is to combine them one day into an artwork that will carry a greater political charge than she usually permits. She calls them her ladies’ army.

“They’re all vintage objects, ideally broken,” she says. “They’ve all lived a life already and I’m calling them all to arms.”

To step inside her studio, an expansive light-filled space in inner-city Paddington, a short walk from her home, is to encounter an assortment of distraction and creativity. A selection of paints neatly sorted like an art supply shop. A wall calendar showing three months of appointments. A vase full of native flowers. Promotional posters from her two films. Art books. A carpet splattered with paint. A large painting in progress.

Everything seems at once impulsive and deliberate. Barton, 44, has multiple projects on the go that demand order and discipline — the most pressing is an upcoming exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, her first survey show in a state gallery — but she also needs a certain amount of impulsivity and freedom to grow as an artist. It’s a delicate, necessary balance.

It means juggling a busy schedule, overlapping exhibitions, two children, two full-time assistants, and an art practice that ranges from filmmaking to painting. But, on the other hand, she is careful to set aside two days a week — “my pure creative days” — in which she shuts herself in her studio to immerse herself in art.

“I’m someone who thrives on order and chaos simultaneously,” she says. “I like things to be a big hot mess, but if it’s too big and messy that’s when my mental health becomes very shaky.”

As the NGV deadline approaches, though, her schedule has been cast aside. “Everything is out of kilter at the moment because of the tragedy I’ve been dealing with in my personal life, and working on some of the most major works I’ve ever attempted.” The tragedy she’s referring to is the death of her mother, Karen, on September 20. This interview is taking place a week after the funeral, and on the day her mother would have turned 71.

“When I spoke at her funeral,” Barton says, “the words I used was that she helped me turn fear into creative expression. She was a wonderful, wonderful mother.”

■ ■ ■

In 2008, Del Kathryn Barton won the Archibald Prize and her world changed overnight. That’s the simple way of telling it, but collectors had already been circling her work before she became a household name. At any rate, Barton remembers a most surreal week. First came the opening of her debut solo show, in Melbourne, then one of her paintings appeared on the cover of Art & Australia, then the Archibald.

Her winning picture was a self-portrait with her two children, Kell and Arella, then 5 and 2. Its title was sentimental and direct: You are what is most beautiful about me, a self portrait with Kell and Arella. “Not only the best but the most emotionally daring painting won this year’s Archibald Prize,” Sebastian Smee wrote in this newspaper following the announcement.

The Archibald also introduced wider audiences to her unique aesthetic: arabesque and decorative, dreamlike and otherworldly, sexually charged and fuelled by feminine power, superficially reminiscent of Gustav Klimt and indigenous dot painting, her pictures represented a compelling, seductive new force in Australian art. This was work that burst with emotion and abundance.

Barton uses the phrase “overactive surfaces” to describe the constellation of marks that give her pictures such vibrancy.

In 2011, Barton was an Archibald finalist again, this time with a portrait of Cate Blanchett. Two years later she won the award for a second time with a portrait of another actor, Hugo Weaving. She gave him the picture: he lives a short distance from her Paddington studio, which also happens to be where her first Archibald-winning portrait is packed away, out of view.

Would she try her luck at a third Archibald win? Probably one day, but she doesn’t have the “emotional fortitude” just yet.

Still, Barton commits to one major portrait a year. Her latest is leaning against the studio wall: it’s a self-portrait with her dog, Cherry Bomb. And it’s large. Beyond that, it’s hard to say much more, since it’s facing the wall throughout her interview with Review. That’s not an accident: “It was the other way around before you arrived.”

“I’m very passionate about portraiture,” she says. “It’s the most disciplined end of a figurative oeuvre, for me anyway.”

They must seem like a lifetime ago, those two Archibald wins. “Of course the winning is wonderful,” she says, “but there’s one thing I would say about working in film that fine arts needs. I love trophies and you get trophies when you win awards. You don’t get trophies when you win in the fine arts world.”

She leans back and laughs, but it’s true. There’s a trophy on her shelf, half-hidden among the stack of art books and other objects. She won it for Oscar Wilde’s The Nightingale and the Rose, named best short animation at last year’s AACTA Awards.

Barton had assembled a heavyweight team: she shared writing and directing duties with Brendan Fletcher; Mia Wasikowska, Geoffrey Rush and David Wenham provided voices; Sarah Blasko wrote the music. But filmmaking proved tough. Nightingale took three years to make and “nearly killed me”.

Barton started to see a psychiatrist and now no longer sees the collaborative nature of film as an “excruciating necessity”. It depends on the collaborators. Her studio manager Liz Ellis, for example, was the lead animator on Nightingale.

“I’ve found the energy of the film industry quite different to the energy of the fine arts industry,” she says.

“Probably because of its collaborative nature I find people a little bit kinder. And that’s something that has been life-giving to me. But at the same time I enjoy the brutal isolation and fortitude you need as a painter, so I think there’s a nice conversation that happens between those two parts of my creative life.”

Two feature-length films are now in progress: her first, Flower, funded by Screen Australia and expected to be in cinemas by 2019, is about an accountant dealing with an “intense erotic fetish for flowers”; the second, still under wraps, will combine stop-animation and live action.

But everything is on hold while she puts the finishing touches on The Highway is a Disco for the NGV.

Visitors to the gallery still will encounter Barton’s work for the screen, courtesy of her second short film, Red. Inspired by the savage mating ritual of the redback spider, it stars Blanchett and features the Sydney Dance Company’s Charmene Yap, actor Alex Russell and Barton’s daughter, Arella Plater. Two lines from Sylvia Plath introduce the action: “Mother of otherness, eat me.” Barton says it’s her first consciously feminist work.

“I’ve always been about the sisterhood, but I don’t like labels, I’m all about the integrity of one’s unique process of self-individuation,” she says.

“When I made Red — and it was a very, very difficult, insane project — I really was moved to dedicate it to all the women in the world. It’s a film that is a celebration, and a fairly brutal celebration in some ways, of female power. Unapologetic female power.”

Barton is an admirer of Louise Bourgeois, whose large spider sculpture Maman has been seen around the world. All of which combines to make Red, which screened at the Adelaide Festival earlier this year, both ambitious and complex in its design. “I wanted it to be a bit f..ked-up. I wanted it to be very sincere — archetypal, elemental, it’s like women are better at managing the magic of craziness.” She laughs again. “Oh my god, I’m already scared to read this piece.”

■ ■ ■

As it happens, Barton clearly articulates what she does and why she does it. Some artists struggle with this part of the art game, but she discusses her creative process with a remarkable level of insight and nuance. It’s also disarmingly candid: “I’m at my best just speaking from the heart, just trusting my capacity to honestly tell my story.”

Her artistic origin story has been told many times. Barton was a child when her family moved from the northwest Sydney suburb of Castle Hill to a run-down old farmhouse in East Kurrajong, close to the Hawkesbury River. For the kids, it was an enchanted childhood, but Barton struggled with depression and anxiety. Her mother encouraged her to take up drawing as a form of therapy.

“It might sound a little bit dramatic to say this,” she says, “but I think that saved me.”

She left home at 17 to study in Sydney. This might have been too young to strike out on her own, she now admits, but that early guidance had left its mark. “I take medication now and that has changed my life and I’m very grateful to be working with an excellent psychiatrist.

“Perhaps if I’d been assessed differently as a younger person there might have been less suffering, particularly in my 20s. Having said that, being encouraged by my mother and connecting so deeply to the practice, but also making paintings, making drawings, was like a lifeline. It certainly set up a very unique, intense, vital and obsessive need to make work, which I think has served me well in many ways.”

There’s a piece in her new show called At the foot of your love. She started making it as soon as she found out that her mother had pancreatic cancer. It was “a devotional work”, a way for her to manage her grief. Plans were being finalised for her mother to travel to Melbourne for the show when she died. “My work is all very personal but this is one of the most personal works that I’ve ever made.”

At the foot of your love consists of 270 images on silk draped over a shell made from Huon pine. Barton wanted the images to combine the “rich, overlapping feminine narratives” of the world. The silk, meanwhile, could be seen as an enormous handkerchief soaking up “the oceans of tears shed for departed mothers”. It’s sentimental, she adds, but it’s “an epic f..king work”.

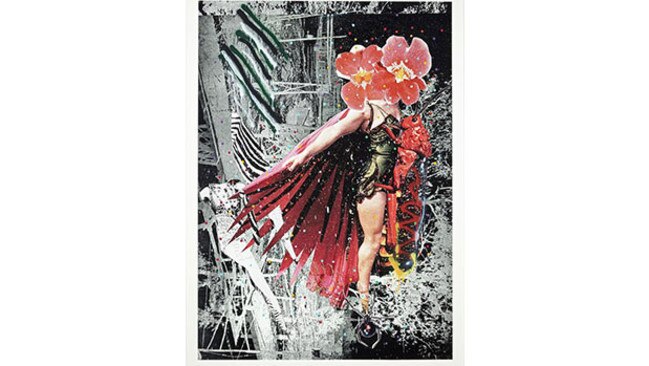

It’s also an extension of another piece in the show, 75 digital montages called inside another land. These images have been pulled together from hundreds of sources, turned into collages, scanned, then finished by hand. They show women’s bodies and flowers in hallucinatory scenes, continuing the themes that Barton has focused on for years.

“Look, I don’t feel like there’s anything uniquely different in terms of content about these works,” she says. “They’re all narratives pertaining to what it is to be female. The blossoming and the power of female genitalia.”

Barton and her assistants also have been scrambling in recent weeks to finish one of the centrepieces for the show, a large, five-panel painting called sing blood-wings sing. The panels are a dizzying explosion of colour and movement that revolve around dragons and the female form. Barton is animating it into a film, the one she is reluctant to speak about. It’s a reimagining of Puff the Magic Dragon, with a female as the protagonist.

The NGV exhibition reveals a new breadth to Barton’s talent, all revolving around common concerns. Volcanic women are 24 ink drawings celebrating female energy. Come home to me is a series of text-based works on paper where words hover in dripping red paint: “milk”, “howl”, “monstrous seed” and so on.

She will also paint a picture directly on to the gallery’s wall. Like so much of her work, the title for that painting — briefly turned into dreams — is poetic, suggestive and elusive.

Barton hates artist’s statements, the kind of texts that elucidate in great detail the meanings behind individual works. Her titles, on the other hand, are simply her way of verbalising her creations.

“They float by me but they hook in and feel right,” she says. “Sometimes they can be cheeky, but mostly they’re deeply earnest and deeply sincere and my offering to an audience. I’m not saying to look at the work in this way, with these words. But if you want me to offer some words to you for you to look at this work, these are the words that I would offer to you.”

They don’t roll off the tongue, though. Try saying sing blood-wings sing out loud and you’ll see the issue. Barton laughs again, but says the meaning is key. It’s about femininity, coming of age, a guiding energy.

At this point, she feels a surge of emotion. “That was a very hard journey for me and it’s something that I always want to advocate for young women. Pursuing a life in creative industries is impossibly hard and you have to bring your most vulnerable best self to that, and it’s harder than it looks.”

Which brings her back home, to her original source of creativity. The great sadness of this new show is that her mother won’t be there to see it, but Barton has another tribute in mind. She’s planning a new tattoo in her mother’s honour. She had her first done when she turned 40, as a nod to her immediate family. All her tattoos are symmetrical: the one on her left arm, for instance, is mirrored on her right. They were done in her studio by tattoo artist Stanislava Pinchuk, also known as Miso.

“I’m not a religious person, so art for me is my religion. And getting a tattoo in the studio with a beautiful lady friend is a church I want to be in.”

Del Kathryn Barton: The Highway is a Disco is at NGV Australia from November 17 to March 12.