De Beauvoir: affairs of her art

Simone de Beauvoir wrote her first book at seven.

Simone de Beauvoir wrote her first book at the age of seven. Inspired by a similarly precocious writer, Jo in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, she then read Virginia Woolf and the Brontë sisters in English. By age 12 she had finished George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss.

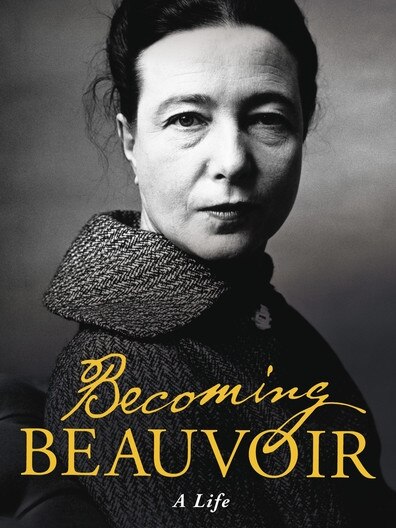

Though she wrote that ‘‘there is no instant in a life where all instants are reconciled’’, the instants Kate Kirkpatrick assembles in her biography, Becoming Beauvoir, form a portrait – provisional, shifting, dynamic – of the legendary French writer and philosopher.

Kirkpatrick is the latest in a line of de Beauvoir biographers. She takes her cue from her subject’s suggestion that ‘‘one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman’’, which has been crucial in unhooking ideas of gender from biological sex, opening the way for subtler ways of thinking about the construction of gender. It also suggests the importance to de Beauvoir of continual growth, propelled by reflection. Inspired by philosopher Henri Bergson, she imagined life as a ‘‘progress’’ and ‘‘living activity’’.

Kirkpatrick focuses on the formation of the woman who, by the end of her life, had been ‘‘a celebrity for forty years; loved and hated, vilified and idolised’’. She became an iconic feminist product, a brand. Kirkpatrick looks beyond fixity for flux as she explores the writer’s development into someone who had an impact ‘‘not only on readers’ imaginations but on the concrete conditions of their lives’’.

By the time de Beauvoir died, aged 78, in 1985, eight hours short of the first anniversary of the death of philosopher Jean Paul Sartre, her beloved intellectual companion of many decades, her legend and his were inextricably bound. In her case, some of the bindings were skeins of a sexist narrative.

The legend of their pact, ‘‘forsaking no others’’ to be one another’s ‘‘essential love’’, with ‘‘contingent loves’’ on the side, has expanded into the myth of a decades-long passion. This has been sustained by a conventional assumption that all women want ‘‘lifelong monogamy with men’’, which situates de Beauvoir as the luckless cast-off pining after a feckless philanderer.

This elides key aspects of de Beauvoir’s experience: bisexuality and the complex intersections of Sartre’s and de Beauvoir’s polyamorous relationships, elisions aided by redactions in the writer’s own journals.

Kirkpatrick corrects this, drawing on recently published material and depicting an independent subject, rather than Sartre’s languishing sidekick. Kirkpatrick is not the first to aim for a truer portrait, though her emphasis is new.

Reading the existing biographies in 1994 – before writing her own, which focused on de Beauvoir’s intellectual life – philosopher Toril Moi commented ‘‘one may be forgiven for concluding that the significance of Simone de Beauvoir derives largely from her relatively unorthodox relationship with Sartre and other lovers’’.

There’s a clear irony in caging de Beauvoir, who subjected the word ‘‘love’’ to ‘‘decades of philosophical scrutiny’’, in a conventional love story.

Kirkpatrick draws on de Beauvoir’s newly available letters to Claude Lanzmann, the French filmmaker acclaimed for his 1985 documentary, Shoah. Lanzmann was the only lover she referred to by the French familiar pronoun ‘‘tu’’. With him, in middle age, she ‘‘leapt back enthralled into happiness’’.

Instead of the faithful woman flailing in a womaniser’s wake, de Beauvoir was the beloved centre of an abundant (and tangled) love life. Sartre ‘‘is in my heart, in my body and above all (for in my heart and my body many others could be) the incomparable friend of my thought’’.

What if, Kirkpatrick suggests, the ‘‘great love story of the century’’ was ‘‘ultimately the story of a friendship?’’. De Beauvoir wrote that she ‘‘wanted a love that accompanies me through life, not that absorbs my life’’. Kirkpatrick considers love as part of the intellectual and creative weave of her subject’s life. De Beauvoir’s grounded, domestic life – important to her writing – is less in focus.

Quoting Woolf that ‘‘there are some stories that have to be told by each generation’’, Kirkpatrick responds to the work of previous generations: Beauvoir’s own, and that of her biographers and critics.

While she advocates for de Beauvoir, contesting various criticisms, she allows complexity. De Beauvoir claimed the freedom to ‘‘love several men in ways she thought them loveable’’ but some ‘‘contingent loves’’ felt diminished, such as her married lover who wanted more than ‘‘the crumbs … you both offer me with such elegance’’.

Philosopher Julia Kristeva called the couple ‘‘libertarian terrorists’’. While Kirkpatrick comments that ‘‘it is impossible to piece together a complete picture’’ of her relationship with her former student, Bianca Bienenfeld, de Beauvoir wrote that ‘‘we have harmed Bianca’’. Bienenfeld’s analyst (Jacques Lacan, no less) agreed.

Deceit and heartlessness may be liberty’s problematic bedfellows. Sartre cut and pasted his love letters (he could ‘‘praise the unique irreplaceability of several women at once’’) but it was she who lost her teaching position as a result of ‘‘suspicious living arrangements’’.

While de Beauvoir’s affairs were not always easy (she describes American writer Nelson Algren as her ‘‘pang collector’’), Sartre remained an anchor, her ‘‘dear little absolute’’.

De Beauvoir wrote of tearing herself away from ‘‘the safe comfort of certainties’’ in a continual search for truth. She wished every human life could be ‘‘pure transparent freedom’’.

Developing a form of autofiction (Blanchot used the term ‘‘thesis novel’’) that predates the work of 21st-century writers – including Maggie Nelson, Melissa Febos and Yiyun Li – de Beauvoir’s self-examination was clear-eyed and even harsh. Becoming, as a state, resists stasis.

Meticulously and engagingly, Kirkpatrick catches myriad ‘‘instants’’ of the flux behind the icon.

Felicity Plunkett is a writer, poet and critic. Her new poetry collection is A Kinder Sea.

Becoming Beauvoir: a Life

By Kate Kirkpatrick

Bloomsbury, 448pp, $40 (HB), $26.99 (PB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout