David Williamson puts down his pen after 50 years in Australian theatre

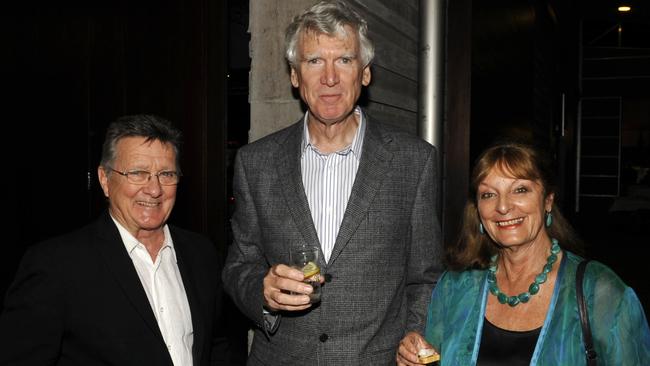

Playwright David Williamson is putting down his pen after 50 years at the top of Australian theatre. He and old mate Graeme Blundell catch up over lunch.

Playwright David Williamson is hanging up his pen after 50 years at the top of Australian theatre. He and old mate Graeme Blundell catch up over lunch.

-

David Williamson: I’m finished. After 50 years I’m honestly glad to be out of it. Look, I’ve had a very fortunate 50 years, just about everything I’ve written has been produced and usually a good production.

Graeme Blundell: Yes, they have been many memorable productions.

W: I can’t complain really. Compared with the lot of some writers who struggle to get shows on it’s been a blessed life. I count myself lucky, I had 50 good years and theatre companies have even realised I’ve been around for 50 years with the Melbourne Theatre Company and Queensland Theatre doing a revival of Emerald City. And Sydney’s got two new plays. I think they’re good ones too.

B: Tell us a little about them. Crunch Time is one of those “meaning of life” plays I gather from the publicity.

W: Oh, is it? Well, I better go and see it then. And work out what it’s all about (laughs). It’s actually a family drama about an irreparable rift triggered by acute sibling rivalry, which seems to be a constant fact of human life. One of his sons hasn’t communicated with Dad for about seven years, refuses to, and Dad finds out he’s got pancreatic cancer, six months to live. He’s in NSW so he can’t go to Victoria for assisted dying because you have to live there for a year. So he has to try to get his sons together to organise a way of exiting gracefully without withering away to a skeleton, which he doesn’t want to do. He doesn’t want to be remembered as a living human wreck. It’s about a wrecked family trying to repair itself before Dad dies. It has its black comedic moments.

B: Has one of your plays ever been without these black comedic moments?

W: No, no, not really. But the funny lines come out of recognition of character. The truth is the human dilemma, and we’ve only just slowly discovered it, is that most of our decisions are well and truly made by our ancient limbic emotional system before our frontal reasoning cortex even becomes aware of it happening. So most of our brain power is used to rationalise these very bad decisions that have already been made by our primitive emotions.

B: And you and I have made quite a few of these in our lives.

W: Yes, yes, yes. Both human comedy and human tragedy springs from that fact. We are very strongly driven by our emotional needs and we try and pretend we’re not — we try and pretend we are rational creatures, which gives rise to a lot of human tragedy and also a lot of comedy. Someone said — the best definition of comedy I’ve ever read — is when you see the actors on stage behaving very badly and not realising they’re behaving very badly, though we the audience do, basically hurting themselves, it’s comedy. If they’re doing it and hurting other people then it’s tragedy. There is a lot of comedy in Crunch Time but it’s also about facing life’s big issues, those that as we become older, as I become older and you become older, we all face.

B: We certainly do. How is your family, by the way? What about the other new play, Family Values on with Griffin Theatre Company at the SBW Stables Theatre, the old Nimrod?

W: It’s a tough little piece, I think. It’s the old trope of siblings who have hurt each other but have to come together because their father, who is a retired High Court judge, is having his 70th birthday. They don’t want to be there but it’s always good drama when you bring people into the one room who don’t want to be there. One daughter is an activist and has taken strong objection to our treatment of the refugees on Manus and Nauru and has decided to hide a young Iranian woman fleeing from community detention while the government is trying to send her back after three suicide attempts. She wants to hide her out in her father’s holiday home. It’s a family explosion when they all meet. The father obviously doesn’t want his career damaged in any way but his wife is more progressive. It’s family mayhem. At its base it’s saying one of the greatest lapses in governmental moral behaviour is sheer political stubbornness. They could bring all those poor bastards ashore now and the boats would never come, whatever they say. They’ve put humanity in their back pocket. Again, there is a lot of black comedy. One thing is certain — I’ve got five kids and 14 grandchildren and it sure keeps you in touch with family tensions. How are you doing on that front?

B: Not all that great. (Laughter).

W: Come along.

B: Love to because it’s a celebration of the Stables’ 50th too, isn’t it, the theatre originally the Nimrod started by John Bell and the Horlers.

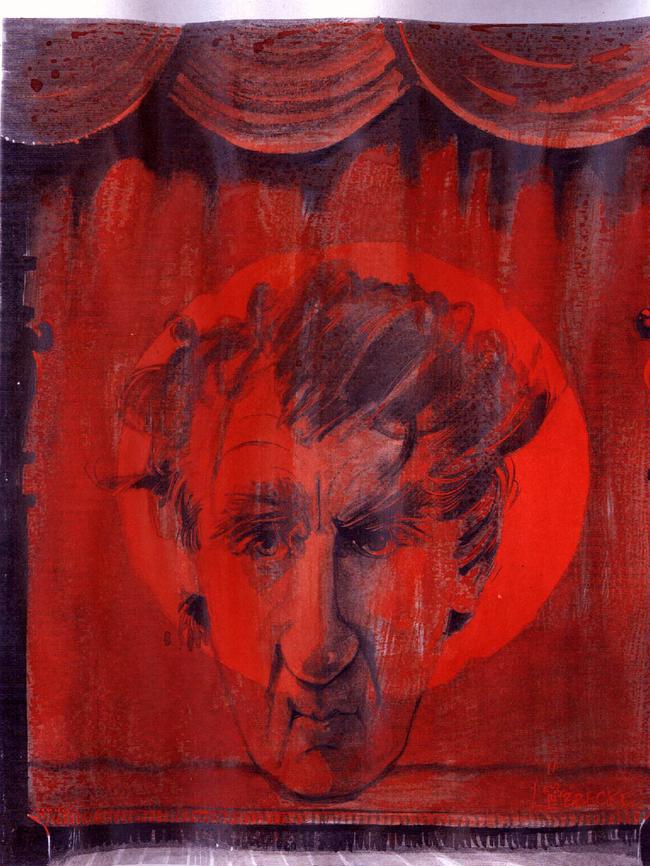

W: It’s really lovely because I’m going back to the space that in a sense really created me, where John Bell directed The Removalists in the early 1970s. But look, I don’t want to downplay the enormous contribution I got from the Carlton theatre in Melbourne when I actually started writing. The original production at La Mama was terrific and I’ve always been grateful to Bruce Spence who was behind it and was Stork in The Coming of Stork in 1970. I still though remember one of the earlier works when the director came out and said before it, “we’re going to show how good acting can bring a dead script to life”. A good line. I give credit to you and those Carlton guys like Bruce and Alan Finney — if it wasn’t for that production of The Removalists, which John Bell came down from Sydney to see and decided to do it in Sydney, it would not have started my career.

B: What’s that story about Bell not reading the play?

W: Actually, John had the script for some time before seeing it and didn’t initially get round to reading it but his wife, the actress Anna Volska, did. She read it in the bath one night and he remembered her laughing so much she nearly drowned. She said it was the best satire on Australian male behaviour she had ever read. She read the genre correctly whereas in Melbourne it was disdained as a play about police brutality. He quickly came down to see it in Melbourne.

B: After The Removalists at La Mama I did Don’s Party, that comic study of middle-class marriage in Melbourne, at the Pram Factory in Carlton and you became famous in theatrical circles very quickly, really, didn’t you? But it was a battle to get Don’s Party actually on given the company’s experimental bent — the script just wasn’t radical enough.

W: It was realism; it was naturalism, which was even worse, though I’ve never worked out just what the difference is.

B: I never knew that either. Still don’t (laughs).

W: I sneaked into rehearsals one day and I heard a furious debate going on that as director you were trying to cope with — I won’t name the actors — but the actress said, “if they are that f..king unhappy why don’t they f..king get divorced?” So I shrank out of the building.

B: But the play was very successful back then and gained the Pram much media attention.

W: And that attracted the Jane Street Theatre to do it in Sydney. The critics in Melbourne didn’t give it much shift but in Sydney it was a different ball game. They went, “oh wow, something is happening here”. But your production was good and so was Spence’s The Removalists, though I unfortunately acted in it. The advice I got later was, “stick to the writing”.

B: But there was a lot of animosity in the emerging underground theatre community wasn’t there?

W: Yes, it all became a little strident. Bob Ellis said I didn’t write The Removalists, that it was just a workshop and the actors improvised it. There was antipathy back in those days — establishment theatre was anything that wasn’t Carlton — but I’m forever grateful for those early productions and I’ve never knocked what they did for me. Carlton was the spring point for what happened next.

B: Yes, The Removalists was taken up commercially by Harry Miller and toured nationally …

W: And then it went to London, got some prizes and Australians with the full cultural cringe at that time thought, “well, if it got prestigious prizes in London it must be all right”. Some of the early reviews of The Removalists were along the lines of “Blood for blood’s sake” and “Two-dimensional stereotyped characters” and “Realism”, all that sort of stuff. The bible at the time was the Tulane Drama Review from America and that was all about breaking theatrical boundaries …

B: Yes, improvisation, group creation, environmentalism …

W: My salvation was that audiences came. And kept coming. And they’re still coming, all these new productions are booking really well. So, I’m getting out while they are still coming. I don’t want to be wandering around at 98 wondering why there is no one in the theatre.

B: You’ve always been one of this country’s great popular entertainers, much closer to your audience than your critics. And you have always understood that audience.

W: In the 80s I became very unfashionable again because I wasn’t a minority writer. It became apparent that there was not just one voice in Australia but many voices and many of those voices weren’t being heard. And it was true. So I was the figure of hate that was keeping these voices off the stage. I kept saying I’m not keeping you off the stage. If theatres would stop doing old English farces and bloody esoteric German plays they could put on some of these writers as well as me but, no, they had this strict formula — 30 per cent Australian, 40 per cent classical and 30 per cent overseas hits.

B: Well, for a time there in the 80s you were omnipresent, especially with the STC. People spoke of two economies, that of the Australia Council and the so-called “Williamson economy”, the productions of your plays — I think there were 17 or 18 — worth more than $80m. Then you were jettisoned, abandoned.

W: Ironically, I was abandoned in 2006 when Cate Blanchett and Andrew Upton came in to run the company and that was after Influence in 2005, which had been the company’s biggest hit, even brought back for a re-run. I should have felt secure. Andrew spoke to me. He said they were moving on and there would be no more Davids any more; we’re not relying on David Williamson, David Hare and David Mamet any more. They had changed philosophy, he said. We don’t now depend on playwrights to bring in audiences — we’re concentrating on actors and great performances. Playwrights were redundant. So the STC started looking for vehicles for great performance. In a way, no longer part of that scene, Sandra Bates at the Ensemble rubbed her hands with glee and I’ve been their mainstay for many years now and without boasting too much I’ve been their top drawcard for years. I’ve been very happy there.

B: Well, they certainly attract the best actors these days and the audience has really opened up.

W: Basically, they still program plays that people want to see rather than plays directors want to produce or stars want to star in. I mean, it all changed a decade or so ago. Directors were no longer directors — they were theatre-makers. They reworked the classics, rewriting them for contemporary audiences. One said, “it’s easier, we know the stories work”.

B: Ironically, it’s the period that TV starts to open up.

W: Yes. If you want to see the great stories you go to television. For me, though, the stage is still the arena that explores language, the way people use it, misuse it, use it to misrepresent themselves, to promote their own cause, to fool themselves. I just delight in the way language is misused by human beings.

B: Do you know actually how many plays you have written across this five decades?

W: Someone counted up 52 or 53 of them. And someone also counted up the number of productions my works have had in mainstream and community theatres and in the last 30 years or so there have been 760. But there’s this guy called Shakespeare who’s got a few more. And he isn’t even Australian.

B: A simple question people might ask — do they get any easier to write? Plays just seem to flow out of you.

W: No, I basically love to get characters together who shouldn’t be together and try and work their problems out. It’s what causes drama and it’s the conflicts between people and the way they use language to try and resolve or not resolve those conflicts that makes the drama. But the thing still has to have dramatic momentum. If you write something and it doesn’t follow that rule that David Mamet laid down — he was asked why people come to his plays and he said, “to see what happens next” — you lose the audience. So, you have to structure them and I tend to write 10 to 15 drafts. The fit is whacked out — get all the ideas, get the characters, get the context. I usually start with the characters and the conflicts between them and then I know pretty well where it’s going but then again the process is somewhat organic and new ideas come to you as you keep drafting. The first draft has a lot of energy but it’s a bit chaotic and then it’s refined down and down because structure is all-important — as Shakespeare worked out, you can’t waste words. Look at the start of King Lear. You don’t waste time in drama. On the other hand you have to have characters who live. If a play is just about how language is used it becomes a character study and loses dramatic momentum. You are gone then.

B: So the approach hasn’t changed a great deal?

W: No, I learned that at the very start. The big kick is putting all those words together and seeing good actors and directors work on it and then finally seeing that live connection between the audience and play, and those gems of moments when the audience gets so emotionally involved they start interjecting. In one of my plays a guy after a few drinks at interval actually threw a punch at an actor playing a rather despicable character. You know you’ve connected when that happens.

B: Has anything really changed in 50 years in the way you see the theatre?

W: My problem is that I was never really interested in theatre for theatre’s sake. I was never interested in formally breaking the boundaries of theatre; I was never obsessed by the idea of art as innovation that so many people have been gripped by since the Impressionists.

B: Now, we are going back.

W: They broke away and good on them. I studied psychology after engineering. I actually got first-class honours at the end and was going into research in the social psychological area, looking at the way people influence each other in groups and the way they use language to manipulate others to boost their own status. It seemed like something I was destined to do but the stage took over. So I’ve been far more interested in social processes than breaking the boundaries of theatre or representing minority viewpoints, which I’m not entitled to in any case. And I have been writing about the Australian middle class because it’s what I’ve absorbed through what I know. And I’m really glad other voices are certainly flowering. But it’s still the case that over 80 per cent of our theatre-goers are middle-aged Anglo-Celts and they occasionally like to see a story about themselves.

B: And they are still occasionally allowed to …

W: I had nothing going for me in Carlton when I started back then — I was white, middle-aged, and wasn’t even Catholic. The thing that kept me going was that those theatre-goers went to see my plays in numbers and if it had been up to the gatekeepers I would have been dead on my feet. But luckily the audiences kept coming and the gatekeepers realised they had to let one in. I thought I was safe as long as people were coming but that didn’t even prove to be true with the STC. I was desperately out of fashion. But they can’t kill me. I’m killing myself now. And I’m doing it while they are still coming to my plays. There’s no more. I’m 77 and I’ve got 14 grandkids, so I’ve got plenty to do and now there is a good crop of young writers. And I’m glad to be watching them do such good stuff. I’m happy to spend the rest of my life watching other people’s good work.

Emerald City is showing at Queensland Performing Arts Centre until Februrary 29 and at Southbank Theatre (Melbourne) on March 6 to April 18, Crunch Time is showing at Ensemble Theatre (Sydney) until April 9 and Family Values is showing at SBW Stables Theatre (Sydney) until March 7.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout