David Stratton reviews: Darkest Hour; All the Money in the World

Ridley Scott made the shock decision to replace Kevin Spacey in All The Money In The World mid-shoot. Now we see the result.

It’s impossible to consider Ridley Scott’s All the Money in the World, which deals with the 1973 kidnapping of the 16-year-old grandson of oil tycoon John Paul Getty, without taking into consideration the extraordinary events surrounding the last-minute replacement of the film’s second lead actor.

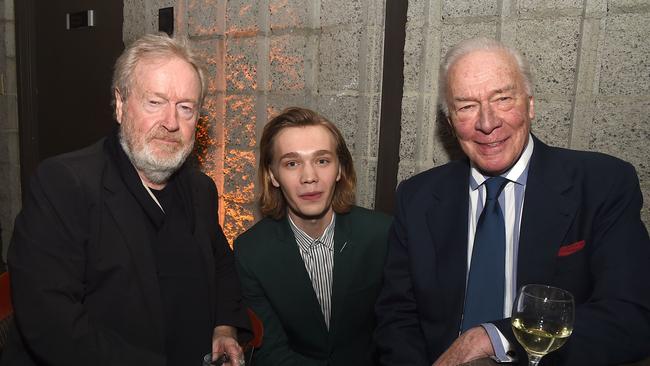

On November 8, Scott announced that, because of the scandal surrounding the accusations of predatory behaviour by Kevin Spacey, who had recently finished playing the role of Getty, the director intended to replace the actor with 87-year-old Christopher Plummer — reportedly his original choice for the role — but that the film would still open on December 22 with a gala premiere four days earlier. Exactly 41 days after Scott made his surprise announcement, the film screened for the Australian press.

What makes this story really interesting is the fact that Plummer’s hastily shot scenes are the best in the picture. Who knows what Spacey would have been like in the role, but Plummer — who bears a passing resemblance to Getty — nails the character of the miserly obsessive, described as “the richest man in the history of the world”, a man who would rather pay millions for a rare oil painting than ransom his grandson. Living in a vast mansion in rural England, surrounded by servants, Getty seems almost uninterested in the fate of his eldest grandson, pointing out that if he paid the $US17 million ransom originally demanded it was likely his other grandchildren might also be kidnapped.

This is a man who is so miserly that he has installed a payphone for the use of his guests. All his money is, we are told, in a charitable family trust, but when he is asked if he ever donates to charity, the answer a firm no.

Somehow Scott, a consummate filmmaker, makes little of this story. A few flashbacks showing how Getty made his fortune and the disdain he seemed to have for members of his family make little impression, and none of the characters on screen is very sympathetic.

Even the hapless John Paul Getty III (Charlie Plummer, no relation to Christopher), who was kidnapped in the middle of Rome in July 1973 and taken south to Calabria where he was hidden for five months until a ransom (nothing like the original sum) was finally paid, is, as written in David Scarpa’s screenplay based on John Pearson’s book, a character with little depth.

When the ransom initially isn’t paid, one of his ears is sliced off (a gruesome scene) and mailed to a newspaper in an attempt by the kidnappers to concentrate the minds of the Getty family, but even this event lacks the impact you’d expect. One of the kidnappers (Romain Duris) seems kind and tries to help the boy; the rest are pretty anonymous. On the other side, apart from Getty himself, there’s Gail (Michelle Williams), the boy’s concerned mother — whose ex-husband is a hopeless addict — and Fletcher Chase (Mark Wahlberg), the operative hired to try to get the boy back. As kidnap thrillers go, despite — or more likely because — this is a true story, it seems strangely unengaging.

Yet it’s beautifully made — Dariusz Wolski’s cinematography is, as usual, very fine — and it’s all handled with a brisk competence.

These are commendable qualities, but we’ve come to expect more from Ridley Scott — and the change of lead actor can’t be blamed, since the scenes with Plummer have, on the whole, more energy and passion than the scenes without him. Typical of the film’s rather lacklustre approach is a scene right at the beginning. “This street is no place for you,” a Rome streetwalker advises the teenager, and a few seconds later he’s being bundled into a van.

All the Money in the World is a curious film and one of the most curious things about it is the fact that, unusually for this sort of fictionalised true story, there are no end-credit photos of the real characters. In fact, Getty III, who, until his death in 2011 at the age of 54 spent most of his life in England, was an ardent movie buff who donated generously to the British Film Institute and was, as a reward, given access to rare films for his private enjoyment.

It has been quite a year for films about World War II and Winston Churchill. Hard on the heels of Churchill (Brian Cox playing the prime minister at the time of D-Day) and Dunkirk comes Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour, which explores how Churchill became prime minister.

Gary Oldman, under a tonne of make-up, plays Churchill very effectively indeed, making much of the man’s eccentricities — constant cigar, ever-present glass of whisky, champagne and fried breakfast in bed. A scene in which his wife, Clementine (Kristin Scott Thomas), complains that domestic bills have been left unpaid seems to suggest the Great Man was also prone to carelessness.

The film, based on an original screenplay by Anthony McCarten (who previously scripted The Theory of Everything), begins in early May 1940. Hitler is studying maps of England while Britain’s ruling Conservative Party, under ailing PM Neville Chamberlain (Ronald Pickup), is discussing a wartime coalition with Labour under Clement Attlee. But Labour insists Chamberlain must resign. His obvious successor is Viscount Halifax (Stephen Dillane), the Foreign Secretary, who shares Chamberlain’s conviction that peace talks with Hitler must be entered into as soon as possible, using the Italian government as intermediary.

This is a position Churchill, who through the 1930s warned about the dangers of German rearmament, strongly opposes. King George VI — an electrifying Ben Mendelsohn — would prefer Halifax to succeed Chamberlain, and the film basically depicts how the king and Churchill gradually come to respect one another.

Meanwhile the collapse of France (“He is delusional!” exclaims a French politician when Churchill demands that the defeated French mount a counter-attack) and the resulting stranding of 300,000 British troops on the beaches at Dunkirk becomes the most pressing problem. A middle-of-the-night phone call by Churchill to US president Franklin D. Roosevelt (David Strathairn) can’t solve that crisis.

Wright’s film isn’t exactly subtle. The story of those alarming days in May unfolds in very broad strokes, and some devices were used to similar if not better effect in Churchill — for example the presence of an adoring but fearful new secretary (Lily James), employed to type Churchill’s dictation while worrying about a close relative who is fighting at the front.

The worst example of this blunt approach comes in a wholly fictitious scene in which Churchill, unaccompanied by minders, takes a London tube and chats to “ordinary” Londoners, asking what they think of the situation.

Armed with this street-level opinion poll he is, according to this scenario, given the strength to face a mostly hostile cabinet and pursue his uncompromising policies. This sequence is simply not believable, and its presence in an otherwise intelligent screenplay is inexplicable.

Oldman is a very fine Churchill in terms of both voice and presence. Pickup’s dying Chamberlain is a surprisingly moving character, and whichever casting director thought of Mendelsohn to play the king deserves some kind of special award. Darkest Hour may be brash, but it’s never less than riveting when actors such as these are doing their stuff.

***

Darkest Hour (PG)

3.5 stars

National release from Thursday

All the Money in the World (MA15+)

3 stars

National release

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout