David Lynch: blockbuster films, cult success

Watching a David Lynch film may leave many wondering ‘what is he thinking?’ A new biography provides some answers.

David Lynch has enjoyed an extraordinary career. Though none of his feature films has been a blockbuster success, they, together with his groundbreaking work in television, have found passionate support and achieved cult status. They have also been enormously influential.

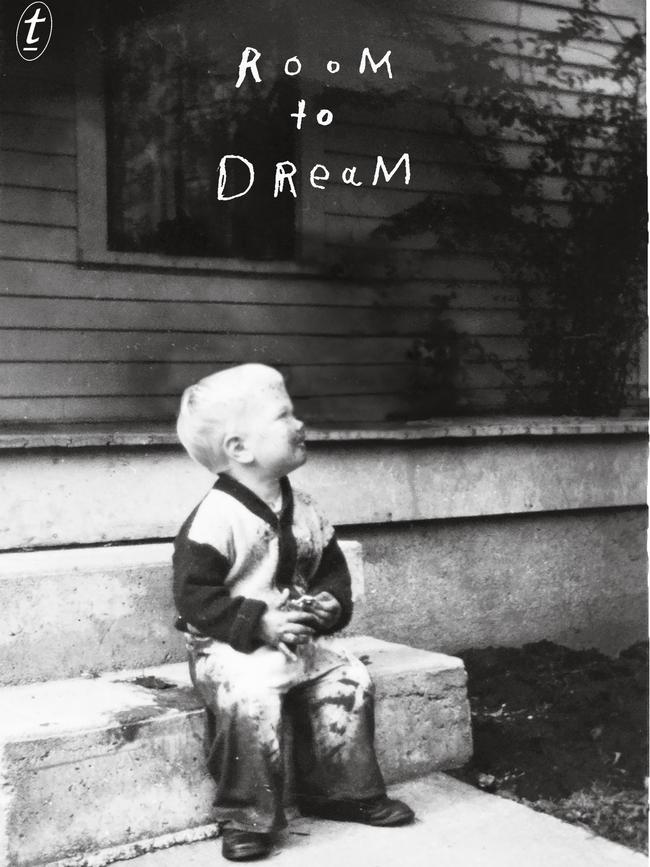

Room to Dream is described as ‘‘part-memoir, part-biography’’ and this duality proves to be extraordinarily productive. Co-author Kristine McKenna, an American journalist and critic, has written a detailed and well researched biography of Lynch. She has talked to his siblings, his friends, his ex-wives and girlfriends, his professional colleagues, and she has, of course, seen all of his work.

She provides an outsider’s insights into the man’s life and work in the best tradition of biography. And then, following every chapter written by McKenna, Lynch provides his personal memories of precisely the same events, which occasionally contradict the information McKenna has gleaned.

For example, McKenna writes that Lynch’s brother John remembers that as a teenager Lynch had greatly enjoyed the John Ford western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, which deals with how legends are created and then handed down to the next generation. But Lynch claims that he doesn’t remember ever discussing movies with his brother, and makes no mention of Ford’s film as an influence (“Movies didn’t mean anything to me when I was a teenager,” he writes).

As a result of this duality, Room to Dream is an unusually satisfying combination of outside observation and inner feelings. It’s like a person having a conversation with his own biography. McKenna describes Lynch’s work as residing “in the complicated zone where the beautiful and the damned collide”.

Lynch was a postwar baby, born in 1946 in Missoula, Montana, where his father, Donald, worked as a research scientist for the US Department of Agriculture. His brother John was born two years later and soon afterwards the family moved to Spokane, Washington, where Lynch’s sister Martha was born. In 1955, the Lynchs relocated to Boise, Idaho, where Lynch spent the most significant years of his childhood.

At school Lynch was popular and, by one account, “a savvy kid”. He enjoyed growing up in relatively small communities close to the spectacular scenery to be found in America’s northwest and its heartland.

Yet from an early age he became obsessive and prone to conspiracy theories (he was convinced Lyndon Johnson was responsible for the assassination of his predecessor, John F. Kennedy). He was also a dreamer. In this book he uses the word ‘‘dreamy’’ constantly.

Bushnell Keeler, the father of one of Lynch’s best friends, steered him towards art and in 1965, at the age of 21, he enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, where he met Jack Fisk, the future production designer and husband of actress Sissy Spacek. Fisk became a close friend. His sister Mary was Lynch’s second wife.

Awarded a $US5000 grant from the American Film Institute, Lynch made his first short film, The Grandmother (1970), and from then on concentrated on cinema and art. “I always say that filmmaking is just common sense,” he remarks.

For film buffs the book is revealing as to the development, production and marketing of all his films, and the critical reaction to them. Eraserhead, which he describes as his most spiritual film, was finally released in 1976, after several tortuous years in production, during which period Lynch started meditating.

The background to The Elephant Man (1980) is unusually interesting as it reveals how intimately comedian Mel Brooks — whose company produced the film — worked on the screenplay and development of what became Lynch’s first commercial success.

The disaster of Dune (1984) makes for especially poignant reading, as Lynch threw himself into this spectacularly expensive production with boundless enthusiasm, only to see it derided by most critics and bomb at the box office.

But the film that followed it, Blue Velvet (1986), though never a blockbuster, was a powerful and corrosive journey into the darkness that, in Lynch’s vision, lurks behind the picket fences of small-town America. His launch into television with the original Twin Peaks (1990) was followed by the Cannes Palme d’Or-winning Wild at Heart (1990), one of his most controversial and violent forays into America’s black soul.

Lynch’s world is a dark and mysterious one. Behind the idyllic small-town settings of Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet, sinister events are taking place and evil is never far away.

Yet there is another Lynchian universe, that of The Straight Story (1999), a deceptively simple road movie about an elderly man who travels a very long distance riding a lawnmower because he’s not licensed to drive a car. This is Middle America, beautiful yet strangely sad, in which memories of a kinder, gentler past are ever present. The Straight Story is a film that evokes Lynch’s rural upbringing.

The book is extremely candid in its revelations about Lynch’s personal life. He has been married four times and has four children, but his numerous other relationships are discussed in some detail by McKenna and by Lynch himself.

I was particularly interested to compare the insights in Room to Dream with my own experiences with Lynch. I met him for the first time in 1986 in Montreal, where Blue Velvet had its official world premiere at the city’s film festival. It was a brief meeting, but I was immediately struck by his slightly absent-minded charm and his “aw shucks” way of talking. He reminded me of the sort of character James Stewart portrayed in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

In 1990, I interviewed him for Wild at Heart. Some directors — Quentin Tarantino is one — are excellent interview subjects. You only have to ask one question and they’ll talk for hours. Lynch isn’t like that. He’s quiet and introverted.

Journalists are invariably allotted only five or at the most 10 minutes for a one-on-one television interview, so we are very conscious that the clock is ticking. But Lynch takes his time, he ponders the question and doesn’t always come up with a useful response. Naomi Watts was able to tell me vastly more about the production of Mulholland Drive (2001) than Lynch ever did or (probably) could.

In 1994 I got to know him rather better. I had been invited to join the jury of the Venice Film Festival, and Lynch was the jury president. My wife and I had dinner with him and his partner, Mary Sweeney, almost every evening for two weeks. The experience proved one thing. David is not a great filmgoer. He had seen some of the cinema’s classics, but was blissfully unaware of much of the contemporary cinema scene. In fact, he didn’t seem especially interested.

The jury was badly divided in Venice that year, and some of the meetings were fractious. Although always calm and polite, Lynch was not a great president. He appeared indecisive and not very engaged.

The film he liked best seemed to be Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, but since Pulp Fiction had won the Palme d’Or in Cannes that year, some of the jury members, myself included, were keener to award some of the excellent entries from other parts of the world. After some acrimony, the Golden Lion was shared between a film from Taiwan and one from Bosnia; Stone came second.

It was hard to reconcile the diffident, charming, polite and yet at times vague and distant character I got to know during those two weeks with the director of such distinctive and harrowing films. There’s that duality again.

Our paths have crossed a couple of times since, most recently in Brisbane in 2015 when the Queensland Art Gallery presented a comprehensive exhibition of his art, David Lynch: Between Two Worlds.

I was asked to handle the Q&A with Lynch, who had never been to Australia before and who stayed in Brisbane for less than 48 hours. He was relaxed, comfortable, and unusually loquacious, and the audience treated him like a rock star.

His status as one of cinema’s most original and unpredictable artists seems assured, and this enlightening and exhaustive book should be an essential way of discovering more about him and his world.

David Stratton reviews films for The Weekend Australian. His books include I Peed On Fellini: Recollections of a Life in Film.