David Bowie exhibition showcases pop star’s defining moments

A major exhibition looks at how David Bowie has been reinventing himself for more than 40 years | TOP 10 VIDEOS

David Bowie is many things to many people: one of the foremost musical artists of the 20th century and beyond; a chameleon who changes his look and sound in response to the world around him; a master marketer; a talented visual artist; a visionary.

All that is just part of his appeal, however, and his ongoing influence on artists from Madonna to Lady Gaga, as well as on the creative arts and popular culture more broadly, is proof of his precocious prescience.

The title of the exhibition David Bowie Is, opening next week at Melbourne’s Australian Centre for the Moving Image, alludes to that appeal as well as the universal inability to pinpoint who he is or to explain him. Bowie, the man, offers as many questions as answers.

“David Bowie’s appeal to people, the reason people are passionate about him, has more to do with the fact that he represents this idea that we can be who we want to be; it’s the kind of freedom to be,” curator Victoria Broackes tells Review. Along with Geoffrey Marsh, Broackes was co-curator of the exhibition at its first home in 2013, London’s Victoria & Albert Museum.

“He’s not constrained by sexuality or by what a pop star is; he’s pushed those boundaries. People feel a very personal connection (with him) because he asks us to look within ourselves for inspiration and personality.”

Broackes explains the show, which has been seen by more than a million people in London, Chicago and Paris, was the result of a fortuitous introduction from music industry insiders.

“We were introduced to Bowie’s manager and discovered he had this magnificent archive, and we came to an arrangement to do the exhibition on the basis that he allows us to use the stuff but wouldn’t be involved in the curation of the display at all.”

The resulting exhibition includes a plethora of material, such as original drafts of song lyrics including for Heroes, Ziggy Stardust, Fascination, as well as character notes by Bowie about Ziggy; also lead sheets for songs including Space Oddity and The Laughing Gnome, written by his musical collaborators. Other ephemera includes leather-bound film scripts and posters, photographs — of Bowie, his early family life and his influences, including a press photo of Little Richard he has owned since the 1950s — video material, including music clips and his films.

His artwork also gets an airing, particularly sketches and storyboarding for the Ashes to Ashes video and an unrealised film project, as well as a self-portrait based on the Heroes cover artwork. Given Bowie’s forward-looking reputation, it was only fitting that the curators revised aspects of the traditional exhibition format. To that end, visitors will wear headphones that sense where they are within the exhibition and play a soundtrack that matches the surroundings.

There is also, of course, a wealth of costumes. Paola di Trocchio, curator fashion and textiles at the National Gallery of Victoria, who will be speaking at a symposium about Bowie’s impact on fashion during the exhibition’s run, believes the fact the archive — particularly the singer’s famous fashion items — exists at all is testament to Bowie’s understanding of his impact on popular culture.

“The clothes have endured,” says di Trocchio. “They’re potent symbols not just for us but for him as well. In this day and age it’s fairly common for artists to hold on to their costumes, but in the 70s it was not so common.”

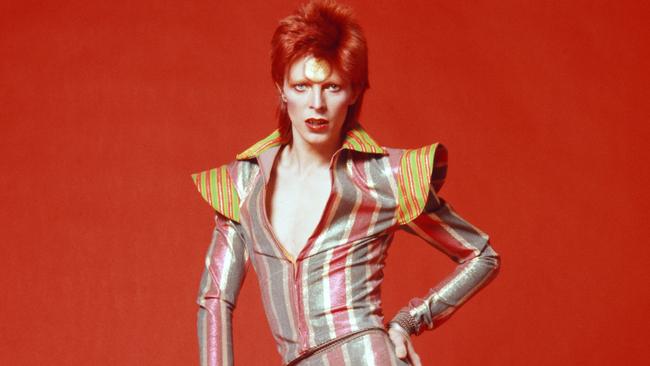

His prescience extended to his visual expression. Embarking on a short stint in advertising after leaving school, Bowie understood perhaps better than most at that time how important good marketing and visual impact were to future success. And while his earliest style was in keeping with the modes of the mid-60s, it was his transformation into a then unexplored androgynous hinterland with the release of The Man Who Sold the World in 1970 that gave the first indication of the individuality that would be the hallmark of his career. He followed that with his alien rock “messiah” character Ziggy Stardust, all Lurex jumpsuits and red spiked mullet, whom he killed off to create the contrasting character of the Thin White Duke with his black suits and cocaine-fuelled thinness.

Along with Marc Bolan, Bowie can be credited with the emergence of the flamboyant glam rock movement.

His first appearance on British TV show Top of the Pops in 1972, performing Starman as Ziggy Stardust, was a pivotal moment in his emergence into the public consciousness.

“There was an extraordinarily strong reaction to it,” says Broackes. “I’ve spoken to so many people who saw it, Mick Ronson (the guitarist with Bowie in Ziggy’s Spiders from Mars band) said he had never seen anything like it. For many people it changed their lives, it broadened people’s horizons. If you imagine Australia in the early 70s it was very similar to Britain, quite a grey scene, and Bowie represented all kinds of possibilities.”

The outfit he wore, a quilted two-piece ensemble design by Freddie Buretti worn with glossy red lace-up boots, is one of many looks in the exhibition, showing off not only the breadth of his personal image but also his ability to work with some of the best creative minds of each period.

One of his frequent collaborators, in particular during the Aladdin Sane tour of 1973, was Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto, a forefather of the contemporary Japanese fashion movement. Yamamoto created some of the most memorable looks of this early period, including jumpsuits from the asymmetric knitted style to voluminous metallic or vinyl styles, as well as designs that drew more on his own Japanese heritage such as kimono styles and embroidered silk ensembles. (Interestingly, Lady Gaga also has sought out Yamamoto for her costumes.)

More recently, in the 90s Bowie collaborated with British designer Alexander McQueen on looks for his Outside tour and on the distressed Union Jack coat for the cover of his 1997 album Earthling, as well as looks for the tour of same. Hedi Slimane is another contemporary designer to have worked with Bowie, creating suiting for his Heathen tour of 2002 when Slimane was the reigning king of contemporary men's wear at Dior Homme.

“Bowie has got his radars constantly on,” says di Trocchio. “The fact that he’s not specifically picking costume designers (to work with) but picking fashion designers who are already out there in the visual realm, he’s always picking up on what’s happening and bringing it into his performances, artwork and music.”

Di Trocchio and Broackes believe Bowie is, above all else, most closely aligned with one of the other great artists of the 20th century: Andy Warhol.

“In a lot of ways he’s almost like the Warhol of music,” says di Trocchio. “He has that quick ability to read culture and to interpret and present what is happening at the time.”

In fact, as well as citing Warhol as one of his many influences, Bowie once portrayed the American artist in the 1996 film Basquiat.

But Bowie’s set of influences goes far beyond Warhol, and includes artistic, visual and performance genres that are testament to his extraordinary curiosity and agility. There are obvious references from areas as disparate as German expressionism, kabuki theatre, mime, Hollywood musicals, film noir, commedia dell’arte, Judy Garland and Iggy Pop. He studied with British dancer and mime artist Lindsay Kemp in the 60s, which di Trocchio believes explains his use of gesture and make-up in his performances.

His acting and performance background has been a constant touchstone throughout his career, whether inhabiting the body of John Merrick in the Broadway production of The Elephant Man, without the use of prosthetics or body-altering costume, or in films as diverse as The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), in which he plays a humanlike alien; The Hunger (1983), in which he plays a rapidly ageing vampire; or Labyrinth, playing a goblin king in the Jim Henson fantasy film from 1986. (Amusingly, he also has voiced a character in the TV series of SpongeBob SquarePants.)

This performance background also made him a natural for the music video, another area in which he was ahead of the pack in the pre-MTV era of the 70s.

His regular collaborator, director David Mallet, who directed several videos for Bowie including Let’s Dance and China Girl in Australia, describes their working relationship as “the ultimate collaboration”.

One example of this was their creation of the video for Ashes to Ashes in 1980. “If you use the analogy of a TV commercial, they are made by a director and from an agency side an art director and a writer,” Mallet tells Review.

“Well, in this case David Bowie was the art director and writer and I was the director. So, for instance, when we did Ashes to Ashes he came to me and said, ‘I have this idea of a clown on the beach,’ and I immediately said, ‘I’ve worked out how to make a completely black sky and psychedelic-looking effect.’ He said, ‘That sounds great, I fancy a bonfire with a whole load of modern romantics.’ And it went on like that. Bang bang bang, within half an hour there it was.”

While Bowie has used a multitude of influences in his own work, he has also been an influence on the work of a multitude of others.

His chameleon-like ability to change personas, looks and musical styles has set an example to artists such as Madonna, Lady Gaga and even Kylie Minogue, all of whom have made a point of experimenting with their image and output, contributing to their longevity.

But beyond the musical world, it is the fashion world that continues a decades-long obsession with Bowie’s image, as evidenced in the exhibition. Designers cite him as an ongoing influence, while fashion magazines are continually referencing him in photo shoots; British style icon Kate Moss has appeared twice on the cover of international editions of Vogue in homage to Bowie (who even tapped her to accept his best male artist award at last year’s Brit Awards wearing one of his Ziggy Stardust Yamamoto leather rompers).

In recent seasons his past looks have influenced collections from designers and labels as diverse as Balmain, Jonathan Saunders and Miu Miu. As fashion writer Tim Blanks told Fantastic Man magazine in 2011: “Bowie’s arrival in the lives of a generation elevated sensibilities to a degree acute enough that those so changed were able to exert similar influence when they became editors, designers, musicians and artists in their later lives.

“But, like Hitchcock, Warhol or Dylan before him, Bowie offers such a banquet of choice in his many manifestations that it’s possible to mine just one period in his career to extract the pure gold of inspiration.”

Nic Briand and Susien Chong, the couple behind Australian label Lover, readily admit the ongoing influence of Bowie on elements of their work, and Briand calls seeing this exhibition in London “a religious experience”.

“Always running through the brand is this masculine-feminine thing rubbing against each other, and that’s definitely from Bowie,” says Briand.

“There are definitive styles that we’ve referenced, we keep trying to re-create that Thin White Duke balloon pant every season, and think, ‘This time we’re going to get it’.”

This winter collection saw the pair reference an image of Bowie during the Diamond Dogs era, when he was photographed with a large dog and wearing a boater. “I think what always captures me is the way Bowie takes these left-of-field, avant-garde concepts and turns them into Top 10 hits,” adds Briand. “That immense creativity that ends up very commercial.”

Having pushed so many boundaries in his early career, Bowie’s influence in the digital age continues. “I think he’s prescient on a number of levels,” says Broackes.

“In the visual medium and with video he was way ahead, but he also put music on the internet before anyone else and even did the Bowie Bond (in 1997) — where performers actually make money from themselves, which other performers followed. And then the manner in which he released his album The Next Day was so utterly masterful, one just had to gasp in admiration.”

Bowie quietly uploaded a video for the song Where are We Now? on his website on January 8, 2013 — his 66th birthday — announcing his 24th studio album and his first in a decade would arrive two months later.

“Everyone knows everything all the time now, so to release that single Where are We Now? in the middle of the night without fanfare was a masterstroke,” Broackes says.

David Bowie is … always one step ahead.

David Bowie Is opens on July 18 at Melbourne’s Australian Centre for the Moving Image.

THE OUTBACK DANCE THAT CHANGED THE WORLD

Singing in a dusty, dilapidated pub in outback NSW, David Bowie in 1983 plucked from obscurity the isolated rural township of Carinda in his music video for Let’s Dance, and in the process transformed the setting into a backdrop for a powerful sociopolitical message about race.

Indigenous artist Christian Thompson may have only been five years old when that video was released, but he well understands the enduring relevance of the film clip, which follows a young Aboriginal couple as they venture to Sydney to find work, before returning home to the outback town.

“The video was a very significant cultural reference point for myself and probably for most Aboriginal people who grew up in the 1980s and 90s,” Thompson says. “[Let’s Dance] was really a significant pop culture sociopolitical moment because it was an international British pop star who presents this video that reflected Australian race relations at that time.”

London-based Thompson, who grew up in southwest Queensland, has created a video work in response to Bowie’s clip. It combines a video self-portrait with a newly composed song called Dead Tongue, written in his father’s native language, Bidjara.

The song was recorded in Oxford, where he was one of the first Aboriginal students to attend the British university on a Charles Perkins scholarship. The video component was recorded last week in the cube-shaped, wooden-walled pods that housed the artists who participated in Marina Abramovic’s Kaldor Art Projects residency. He says the Dead Tongue video was inspired by the Let’s Dance clip.

When Bowie toured Australia in 1978, he reportedly spent his free time exploring the outback in a Land Rover. The experience stayed with him and became the premise for the 1983 video. He would later describe the clip — which, belying the jovial song title, explores the racial tensions Bowie witnessed during his time in Australia — as “very direct”, with a simple message: “it’s wrong to be racist”.

Let’s Dance became Bowie’s second single to top the US charts, while it peaked at No 2 in Australia. The album of the same name, combined with 1983’s globally successful Serious Moonlight Tour, attracted a new legion of fans. The surge in Bowie’s popularity meant indigenous Australia was projected on to television screens across the world, and the glam-rock icon became an unlikely poster boy for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community’s fight for social equality.

Like Bowie, who believed in the use of “the video format as a platform for some kind of social observation”, Thompson recognises the power of video in a new media age. “I grew up in an era where culture mashing was deliberately turning things on their head,” he says. “Video is a familiar entry point for this generation.”

Thompson’s Dead Tongue opens on August 1 at Melbourne’s Koorie Heritage Trust.

Simone Fox Koob