Darkness, my old friend

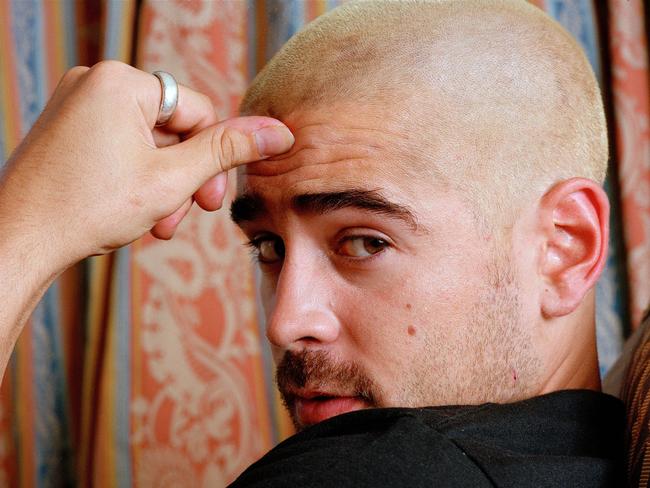

Rare is the actor who offers up mention of a drug dealer within minutes of meeting a journalist. But Colin Farrell is that rare thing.

Not many people know this, but when Colin Farrell was just 18, he spent a year living in Sydney.

Even Martin McDonagh, his close friend and collaborator – the filmmaker who has directed him in 2008’s In Bruges, 2012’s Seven Psychopaths and, now, his Venice Film Festival award-winning performance in their latest project, The Banshees of Inisherin – wasn’t aware of Farrell’s Australian gap year. Both the Irishmen – Farrell, Dublin born and bred; McDonagh, the son of Irish immigrants in London – have close ties to Australia. McDonagh’s sister-in-law hails from Perth. But when it comes to antipodean connections, Farrell wins.

“Went on the one year visa with a couple of mates,” the actor recalls, leaning back in his chair and savouring the memory. We’re sitting in a swanky London hotel room in which Farrell looks out of place in his skinny jeans and jewellery, dark hair chin-length and still wet.

“We planned to backpack and see the whole country but we found a good dealer and we didn’t leave our street for a year.”

Farrell barks out a laugh. The man’s charm is legendary. And he makes the interaction look effortless, courtesy of a combination of genuine curiosity and dogged eye contact. Talking to him feels less like an interview and more like a conversation; rare is the actor who offers up mention of a drug dealer within minutes of meeting a journalist. But Farrell is that rare thing.

He even remembers the exact address of his old apartment in Sydney’s Paddington and the bars he used to frequent. (The Lizard Lounge, Q Bar, both shuttered for good now, remnants of a different time.) “I was so happy there,” Farrell smiles. “Such good memories.” At 18, the kind of career that Farrell has had, aged 46, was far on the horizon. After returning to Ireland, Farrell was cast as Danny Byrne, a brooding bad boy from the big smoke sent to live with his uncle in County Kerry, in Ballykissangel, the popular 1990s soap opera. By 2000, Farrell had broken out in Tigerland, a Vietnam War epic from director Joel Schumacher. One review described him as a “sizzlingly sexy screen presence”.

From there, Farrell was jettisoned into Hollywood’s elite: Minority Report opposite Tom Cruise, Daredevil with Ben Affleck. By 2004 he was headlining Oliver Stone’s Alexander the Great biopic and in 2006 was cast as the lead of Michael Mann’s reboot of Miami Vice. Behind the scenes, though, Farrell’s life was unravelling. Watching Miami Vice at its premiere, he realised he couldn’t remember “a single frame” of making it. “The second it was finished, I was put on a plane and sent to rehab as everyone else was going to the wrap party,” he once shared. Farrell had been battling substance abuse for years. He has been sober since 2006.

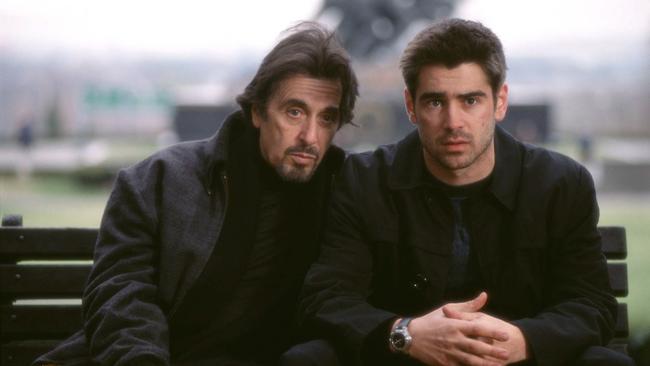

A year and a half later, the actor found himself in a New York hotel taking a meeting with McDonagh. The celebrated playwright – already a four-time nominee at the Tony Awards at that point, soon to be the recipient of two Oscars – was looking to cast his feature debut In Bruges, a black comedy about a pair of Irish hit men recuperating after a job gone wrong in the Belgian city of bridges.

“I was only a year and a half out of rehab, I didn’t know if I still even wanted to act anymore,” Farrell admits. “I’d lost sight of the joy of what a creative experience on a film could be.”

He remembers sitting down with McDonagh and outlining all the reasons why the director should not cast him. “It’s a great script, I bring baggage, people will f. kin' … I wasn’t sure, honest to god,” Farrell shares. McDonagh ignored him and Farrell’s performance as Ray, a tangle of guilt and gallows humour, is still one of his best, earning him a Golden Globe nomination.

“Bruges was a turning point for me – I’m probably only saying this because I read it once,” Farrell laughs, “but you don’t fully separate the dancer from the dance. When I look back at the last 20 years of my life, I see it … through the prism of what film I was doing.” In Bruges remains one of those signposts, marking a shift in his career towards more dramatic work and kickstarting an enduring creative collaboration. “Fourteen years later, life does feel very different for me, and yet, as life can trick you in those ways, it presents as different and things have changed, but fundamentally …” he trails off. Because life changes but it also stays the same: 14 years later Farrell has reunited with McDonagh and his In Bruges co-star Brendan Gleeson on The Banshees of Inisherin, which premiered at Venice to a 15-minute standing ovation in September. The film is now the most nominated movie at the 2023 Golden Globes, with eight nods including one in Best Actor for Farrell.

The film is textbook McDonagh: a fable set in a remote Irish community about the dissolution of a once close friendship between drinking buddies Padraic (Farrell) – a farmer who lives with his sister Siobhan (Kerry Condon) – and Colm (Gleeson), a skilful fiddle player. McDonagh worked on the screenplay for several years, following the release of his 2017 Oscar-winning film Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri, whittling away at plot and characterisation, constantly circling back to the tragedy of a friendship break-up. McDonagh sent an early iteration to Farrell, who loved it. “I thought it was f. king brilliant,” Farrell declares, “but he, of course, wasn’t happy with it, because his standards are very high. Mine not so much. You’ve seen some of my work.”

Farrell read McDonagh’s final script with trepidation. “There’s always a bit of nervousness because I love him so much, and he’s so brilliant, but god, what if I don’t adore it,” the actor explains. “What if I don’t organically respond to it, and I just have to fit myself in because I love him so much and I love Brendan so much.”

He needn’t have worried. The script, with all its heartbreak, had an immediate impact on him. “I was so sad reading it,” Farrell recalls. “I knew it would be fun, we always have a laugh working together, but I also knew Martin does put you in some dark corners at times, in the service of his dramatic needs. I knew I would be sad to go to work on it, but I was thrilled when I read it. It was the most extraordinary thing I’d ever read. I kind of limped away, I thought, ‘Oh holy god!’”

Farrell doesn’t shy away from dark roles. In recent years, the actor has sought out partnerships with directors including Yorgos Lanthimos (The Lobster), Steve McQueen (Widows) and Matt Reeves (The Batman, in which Farrell was unrecognisable as infamous crime boss The Penguin) on films that plumb the depths of human despair. The Banshees of Inisherin plays to Farrell’s strengths in this arena: the unique way he can receive soul-crushing news with a wink and a smile. Padraic’s descent into melancholy is painful to watch, made all the more worse by Farrell’s innate lovability as a performer.

Difficult scenes, such as one in which Padraic is beaten by a local policeman and Colm steps in to drive Padraic home, hung over Farrell during filming. “F. king brutal,” he recalls. “I woke up with a dark cloud over me. OK, well, there it is, I’m grand if I can just stay under it all day.” Farrell can shake off most things when filming, but accessing the depressive side of Padraic “stays with you longer”. When he was a young actor, Farrell found harnessing the vulnerability required for the screen difficult. “I had to think of the worst things happening to the people I love,” he recalls. Now, he explains, he’s a man of 46 and what he knows, plainer than anything else, is that “there’s enough pain in the f. king world, and you just tap into that”. “In all of us,” he declares, animated, “at any given time, love. There really is.”

Farrell can’t cry on command, even though his chosen roles often demand tears. “I really can’t,” he protests, cheerfully, dark eyes creasing like a man who loves to laugh. However, “if you really put yourself into a situation and superimpose a bit of your experience on to the page of what you’re trying to bring to life, at the end of the day, any tears that get released are just uncried tears,” Farrell explains. “They’re tears from when you’re seven, or when you were 13 … That’s what it feels like.”

The release of filmmaking, and of art in general, is something Farrell has found himself thinking about a lot over the course of promoting Banshees, which is a movie about how best to use our short time on this earth. Part of the film’s tension lies in the way that Colm believes Padraic’s life to be a simple one, unencumbered by Colm’s own existential philosophising about great art, even though Padraic’s life is just as fragile, his loves as deep and immutable. But Colm’s understanding of Padraic’s vulnerability is too little, too late.

“Isn’t it so ironic that vulnerability could actually be the strongest foundation upon which you can build a life,” Farrell muses. “At least, to have the most honest life. And certainly as artists, you have to allow that vulnerability. You’re not going around having an open gaping heart in life, you’d just get destroyed, of course. But you have to bring the vulnerabilities to work and allow yourself to be guided by that.” It’s something Farrell has gotten better at as he gets older. “I wouldn’t judge myself as harshly,” he admits, when he opens up now, on screen and off. “I judge myself plenty, but not as harshly, and not through the lens of a young foolish man who’s afraid of what the world will think of him.”

McDonagh believes Farrell’s “vulnerability and sensitivity” is key to his power as an actor. But acting be damned, what McDonagh really loves about Farrell is his friendship. “Colin’s decency and his joy of life,” the director tells me. “I wouldn’t be here without him.”

On the subject of vulnerability and sensitivity, though, Farrell has a counter. “I hope this does not let the cat out of the bag too much, but (McDonagh) hadn’t directed in a while (before Banshees),” Farrell shares. On one of the earliest days of shooting, the filmmaker took Farrell aside and admitted, “I forget how to do this.”

“The strength that it takes to display that vulnerability in that moment!” Farrell says. “Now, by day two he was a dick, an absolute joy to be around,” he jokes, wicked grin on his face. “I love him,” Farrell continues, of his three-time collaborator. “We’ve had a couple of incredible (projects). Two of the f. king greatest experiences with the two lads that I’ve ever had in 25 years of this racket.”

What more could you hope for in this life?

The Banshees of Inisherin is in cinemas on Boxing Day.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout