Cut down in their prime: The fate of our nation’s leaders

Paul Keating once observed that to be the prime minister, you had to want the job with ‘every fibre in your body’. But there is a cost.

The Manner of Their Going: Prime Ministerial Exits in Australia

By Norman Abjorensen, Arcadia, 273pp, $49.99

Paul Keating once observed that to be the Australian prime minister, you had to want the job with “every fibre in your body”. However, there is a cost. All prime ministers pay a price for achieving the nation’s highest office, and for some it is too great to bear.

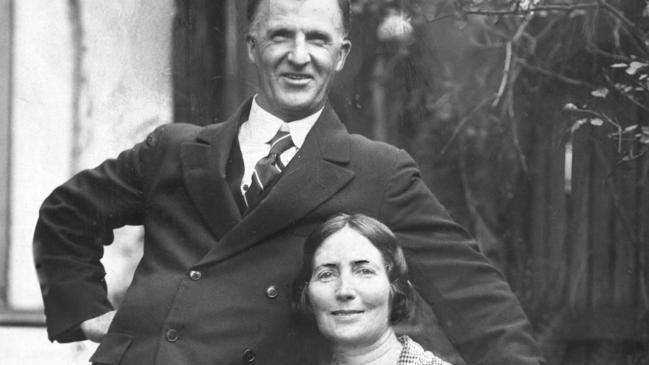

James Scullin was the Labor PM from 1929-31, confronting the Great Depression. Not only did Scullin face an unparalleled economic crisis but the treachery of members of his own cabinet, including his successor, Joe Lyons, and NSW Labor premier Jack Lang, on top of an obstructionist conservative opposition and the hostility of bankers, domestic and foreign.

In The Manner of Their Going, a ground-breaking analysis of the departure of Australian prime ministers from Federation to the present, Norman Abjorensen writes of the dilemmas. The agony of Scullin’s prime ministership comes into focus:

-

“No one involved in the Scullin years was left unscarred by the torrid experience of crisis and disintegration … For Scullin himself, who remained in Parliament until 1949, ‘’haunted by the ghosts of 1929-31, the never-ending pain that it had all gone wrong’, the memories were just as harrowing, probably even more so. Asked in later years, if he proposed to write his memoirs, he replied: ‘’It nearly killed me to live through it. It would kill me to write about it.’ ”

-

Scullin suffered more than most PMs but, as Abjorensen makes abundantly clear, most Australian leaders are exhausted by the role and often end in less-than-elevated circumstances. Abjorensen has already made a sterling contribution to our understanding of Australian politics and history. He has been an editor and commentator and a biographer, always with an insightful reading of the nation’s mind.

He brings those skills of thoughtful evaluation to this book, first published in 2015 and now updated, and displays a comprehensive knowledge of Australian prime ministers at the time of their end.

Only Robert Menzies went at a time of his choice, having served twice and, as did John Howard, demonstrated that he had learned the lessons of his first term as conservative leader. All other PMs have been removed from office and Abjorensen clusters them around distinct exits.

A chapter entitled The People’s Judgments is focused on the ballot box, with Ben Chifley grouped with Billy McMahon, Malcolm Fraser, Keating and Howard. It’s worth noting that all of those changes of government, courtesy of the electorate, represented significant shifts in political opinion.

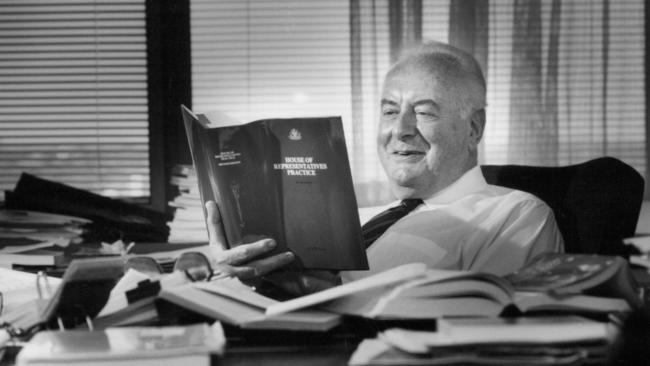

Another chapter, Some May Call It Treachery, groups John Gorton with Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke. Yet Whitlam’s dismissal by the devious governor-general John Kerr hardly represents losing the keys to The Lodge in a manner similar to Gorton and Hawke, who were toppled in internal party coups.

On Whitlam, Abjorensen is scathing in his assessment of Kerr’s misbehaviour, but does not ignore the possible American role in “the Dismissal”. He writes of a most revealing encounter between Whitlam and senior American officials in 1977.

“A curious passage in Whitlam’s history of his Government recalls how, in 1977, when he was once again Leader of the Opposition, US President Jimmy Carter sent his Assistant Secretary of State, Warren Christopher, to Sydney while en route to New Zealand to arrange a meeting with Whitlam.”

Christopher passed on a message from Carter that suggested an understanding of the fraternal nature of the American Democrats and the ALP, and that the president respected the democratic rights of US allies. He gave an assurance the Carter administration would work with whatever government Australians chose.

However, of most significance, Carter maintained “that the US administration would never again interfere in the domestic political process of Australia”.

Now let us be clear, neither the CIA nor any other agency likely played a primary and sinister hand in toppling the struggling Whitlam government.

The Australian establishment from Kerr through Fraser, to Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick, backed overwhelmingly by the Australian media was more than equal to destroying the Labor administration. But Carter’s pledge suggested an unhealthy intrusion by a foreign power in the politics of 1975.

At earlier times, Lyons and Curtin died in office. Both were crushed by the demands of the job. Harold Holt, emphasising his masculinity by diving recklessly into a dangerous surf at Cheviot Beach, simply disappeared.

Others, such as Earle Page, Arthur Fadden, Frank Forde and ‘‘Black Jack’’ McEwen, served for brief periods. Abjorensen covers the field, including the recent lunacy that has gripped both major parties in Canberra, which has made the politics of the Fourth French Republic appear a model of stability.

Abjorensen writes in a narrative that is clear and convincing. He makes the dull seem more interesting than it in fact was. He lifts the mediocre beyond the mundane.

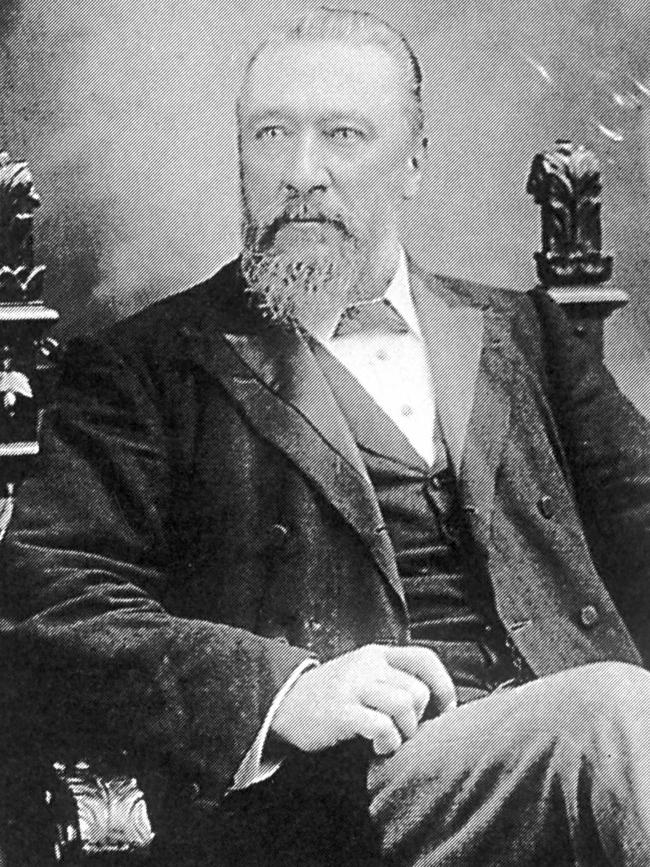

In the opening pages he writes of the ‘‘Hopetoun Blunder’’. This tells the tale of the prime minister who never was, Sir William Lyne, premier of NSW, who was tapped by the governor-general, Lord Hopetoun, to be our first national leader. Thanks to Alfred Deakin’s careful but determined opposition, Lyne was unable to muster a cabinet. The baton passed to Edmund Barton.

Australian prime ministers emerge in Abjorensen’s narrative as human figures whose political commitments are tempered by strengths and weaknesses of character. Their health also plays an important role. There is a revealing epilogue in which Abjorensen details post-prime ministerial lives, from the sad end of Deakin to Chris Watson’s founding of the NRMA.

Menzies enjoyed his retirement, be it as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports or at the MCG.

Australian leaders come under review in this book, from the bastardry of Billy Hughes to the absurdity of Billy McMahon. The best speak eloquently for themselves; the worst emerge in their malice.

Along the way, there are curiosities and quirks, the best being Tony Abbott’s use of an obsolete fax machine to inform the governor-general of his resignation. It may have been odd, but it was a distinctive manner of going.

Stephen Loosley is a senior visiting fellow at United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout