Culture, identity unearthed in the evolution of Indigenous film

From a complete absence to shameful early depictions, it took until the 1970s before Indigenous films began to truly flourish.

Indigenous Australians had been, for the most part, absent in Australian films when Charles and Elsa Chauvel made the pioneering Jedda in 1955. It was the final film of the husband and wife team, but this story about a part-Aboriginal girl (Rosalie Kunoth-Monks) taken from her family to be raised as white – ironically the first Australian feature produced in colour – was an important trailblazer and was distributed in several countries including Britain (where I first saw it) and the US, where it was retitled Jedda the Uncivilised!

The Chauvels cast Aboriginal actors in their film. Not so the producers of Journey Out of Darkness (1967), an inept affair made by an American TV director that premiered in Canberra in the presence of Prime Minister Harold Holt. Set in 1901, the film centres on the pursuit of an Aboriginal fugitive, played by Malaysian born entertainer Kamahl. Hard on his heels is a white policeman who is assisted by an Aboriginal tracker – the latter role played by white actor Ed Devereux in blackface makeup. This was a shameful affair to have been released in the year that our First People were finally recognised as Australian citizens.

With the revival of Australian film production in the 1970s – which was only possible because of enlightened bipartisan support by governments at both federal and state level – films with Aboriginal themes began to emerge. British director Nicolas Roeg’s haunting Walkabout (1971) introduced an extraordinary young Aboriginal actor and dancer named David Gulpilil, who also appeared prominently in Peter Weir’s The Last Wave (1977), a haunting story involving the beliefs and practices of Sydney’s Aboriginal community. The same year, Phillip Noyce’s first feature-length film, Backroads, explored the friendship between an Aboriginal man and a white man and, a year later, Fred Schepisi’s fine adaptation of Thomas Keneally’s novel The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith was a harrowing depiction of Aboriginal dispossession and exploitation during the early days of the colony.

It would be six more years before Bruce Beresford made The Fringe Dwellers, the first feature film featuring an all-Aboriginal cast (apart from the odd white extra). The importance of Beresford’s film – which represented Australia at Cannes in 1986 – cannot be underestimated, but it was not a huge commercial success. Ten years later another white director, Nicholas Parsons, made Dead Heart, a thriller set in Central Australia, that marked the screen debut of Indigenous actor Aaron Pedersen.

In 1993 the Australian Film Commission – forerunner of today’s Screen Australia – under CEO Cathy Robinson and chair Sue Milliken (who had produced The Fringe Dwellers) – established an Indigenous Branch headed by Wal Saunders. This initiative encouraged the production of Indigenous short films by filmmakers such as Ivan Sen, Leah Purcell and Darlene Johnson.

Another trailblazer was Tracy Moffatt’s Bedevil (1993), not only the first feature by an Indigenous director but a woman at that. A wholly original, highly stylised collection of ghost stories, the film is still one of the most intriguing and unusual works ever to have been made in the country.

Sadly, Moffatt’s distinguished career took her in other directions and she hasn’t made another feature.

Meanwhile in 1992 Rachel Perkins had founded Blackfella Films, a company established with the aim of producing Indigenous drama for cinema and television. In 1997, Perkins directed her first feature, Radiance, an adaptation of Louis Nowra’s play about three Aboriginal sisters (Deborah Mailman, Rachael Maza, Trisha Morton-Thomas); the cinematographer was Warwick Thornton.

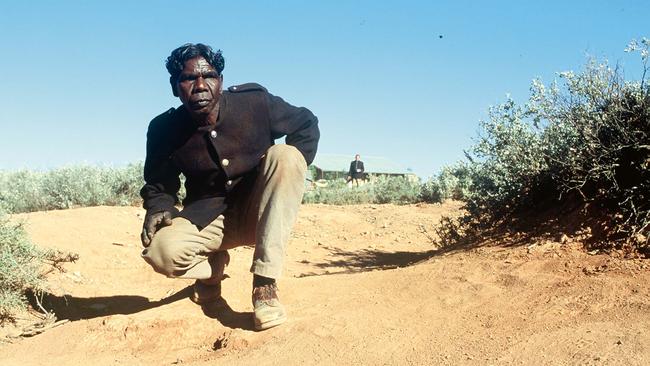

At the turn of the century there was something of an explosion of Aboriginal cinema. Ivan Sen’s first feature, Beneath Clouds, a road movie featuring a young Aboriginal couple, premiered at Berlin in 2001, and the following year two white directors who were passionate about Aboriginal culture, Phillip Noyce and Rolf De Heer, made seminal films: Rabbit Proof Fence and The Tracker – David Gulpilil gives remarkable performances in both.

The former film, based as it was on a true story of children, victims of the Stolen Generation policy in West Australia, finding their way back home, was attacked by some commentators (this writer was pilloried by Andrew Bolt for favourably reviewing Rabbit Proof Fence).

The Tracker, which has a plot similar to that of the notorious Journey Out of Darkness, was the first of three films made by De Heer with Gulpilil: the others, Ten Canoes (2006) and Charlie’s Country (2014) are equally impressive. As a result of this unofficial trilogy, Dutch-born De Heer can well claim to be a leading director of Indigenous films in this country.

Ivan Sen, whose mother was Indigenous and whose father was Croatian, followed Beneath Clouds with Toomelah (2011), which was filmed in the community on the NSW-Queensland border where his mother was born and raised. A vivid but desolate depiction of the life of an Aboriginal boy living in abject poverty, this is a deeply troubling work.

Two years later Sen successfully tackled an outback film noir with Mystery Road in which Aaron Pedersen played the cop investigating a series of killings. It was so successful that there was a sequel (Goldstone, 2016) and a TV series, episodes of which were directed by Rachel Perkins and Warwick Thornton.

When Thornton’s first feature, Samson and Delilah, screened in Cannes in 2009 it had an immediate impact. Told almost entirely without the use of dialogue, this masterly film about the desperate lives of a young Aboriginal couple won the coveted Camera d’Or for Best First Feature. Thornton followed it with The Darkside (2013) which, like Bedevil, is a collection of supernatural stories told in an unorthodox fashion. Equally unorthodox is We Don’t Need a Map (2017), Thornton’s film about right-wing racism, which he made the same year that Sweet Country, a film about white man’s justice in a remote part of Australia in the period after World War I, won the Jury Prize in Venice.

These are all serious, sometimes shocking, movies – but Indigenous directors are more than capable of being whimsical, as Rachel Perkins demonstrated with Bran Nue Dae (2009), an exuberant film version of the stage musical. Perkins subsequently made sobering stories both for television (Mabo, 2012) and cinema (Jasper Jones, 2016). Wayne Blair also chose a light approach with the very popular The Sapphires (2012), another screen version of a stage success, and Top End Wedding (2019).

White Australian directors who have successfully filmed Indigenous stories have recently included Stephen Johnson (Yolngu Boy, 2000 and High Ground, 2019), Imogen Thomas (Emu Runner, 2018) and Victoria Wharfe McIntyre (The Flood, 2020).

All of these stories, whether told by black or white directors, are vivid reminders of the lives lived by Indigenous Australians either in the past or the present. One of the images that stays with me constantly comes from Charlie’s Country. David Gulpilil’s Charlie has been sent to prison for what seems like a trifling offence. In a lingering close-up this noble old man’s white hair is cut and shaved in preparation for life in a jail cell. As a symbol of violation and degradation, the scene is made the more powerful by the actor’s dignified performance.

From Walkabout until now, Gulpilil has given us a series of great performances in films of all kinds. He’s a fine actor, a majestic presence, and a true national treasure.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout