Crime writers Robotham, Cavanaugh and Doyle on top of their dark game

Michael Robotham, Tony Cavanaugh and Peter Doyle live up to their reputation as fine Australian crime writers.

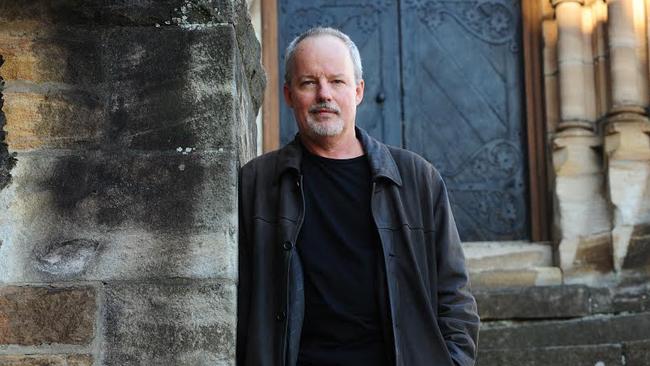

Sydney author Michael Robotham is now recognised as one of the international masters of the dense psychological thriller, having recently won the British Crime Writers Association Gold Dagger for the best crime novel of the year. It was for his stunning stand-alone thriller set in Texas, Life or Death, which was inspired by a cutting from The Sydney Morning Herald in 1995 about a double murderer, Anthony Lanigan, who escaped from jail the day before he was due to be released.

Few crime novelists research criminal psychology and forensic pathology more assiduously than this former journalist — he has a cadre of profilers and former policemen to call on — but he’s also a writer whose prose is a pleasure to read, unlike many of his contemporaries who type rather than write.

He’s back with another of his Joe O’Loughlin novels, Close Your Eyes (Sphere, 392pp, $29.99). His redoubtable hero is now well known in dozens of countries: the sad psychologist and reluctant criminal profiler battling the rigours of Parkinson’s disease. He calls his illness Mr Parkinson and in his dreams he’s a bent, crippled, skulking figure, “the Gollum of my nightmares, scuttling after me, pulling at my body, trying to make me play with him”. It’s not his only battle.

O’Loughlin’s has been a continuing story of estrangement and hopelessly misplaced optimism throughout this series as he clumsily tries to salvage his marriage to his not-quite-yet-ex-wife Julianne and understand his daughters Charlie and Emma. An instinctive observer of others — those almost imperceptible tics, gestures, shrugs and mannerisms — he’s not sure that his function in life might just be to soak up pain so others have happier, sweeter lives.

Early in this new novel his wife throws him what might be a lifeline when she invites him to spend the summer with her and the girls. He jumps at the chance even though he can hear a small alarm bell pinging in his head. But as he thinks of leaving behind a career that has almost destroyed him, along comes a phone call that throws him back into his former life of reading the motivations and impulses of killers.

A mother and her teenage daughter are found brutally murdered in a remote farmhouse, one defiled by multiple stab wounds and the other left lying in her bed, suffocated with a pillow. A reddish brown five-pointed star framed by a circle is smeared above the fireplace, seeping out of the plasterwork as if the wall is bleeding. Again written in the first person and presented in that now so distinctive grave, elegiac tone that cuts through the nightmarish crimes, this is another captivating novel from this accomplished author.

Tony Cavanaugh returns, too, with his equally distinctive hero Darian Richards in Kingdom of the Strong (Hachette, 358pp, $29.99), and again it’s an intense, brooding and disquieting experience.

Like Robotham, Cavanaugh has been discovered in Europe, celebrated for a style that is abrupt, mordant and pointed. There’s nothing extraneous, though he has a gift for writing seductively about place, especially the Noosa River in Queensland’s idyllic Tewantin, a land of sarongs and hammocks, where Richards, the former top Melbourne homicide cop known then as The Gun, lives in the sunshine.

In this new novel he’s tracked down by his old friend Copeland Walsh, the Victorian police commissioner nicknamed Copland because he’s a walking encyclopedia of the land of the cops. He asks Richards to help clear an old case: the death of 18-year-old Isobel Vine, found hanging by a man’s tie in a house in South Yarra. Twenty-five years earlier the coroner delivered an open verdict, balancing suicide, self-inflicted accident and murder — but a blemish stuck to the four young cops present the night she died.

Now one of them, Nick Racine, has been nominated to replace Copeland and the bureaucracy wants the stain removed. Cavanaugh says that with this book he is trying to fold themes of abandonment and betrayal into a whodunit. “Kingdom was a much-needed departure for me in that the first three books were essentially cat-and-mouse psychological games between Darian and a killer, who was revealed quite early on to the reader.”

And Cavanaugh skilfully explores the psychology of the various suspects, playing with the way memory messes with the truth, “polished and revised, shaded in this way and that, over time”, especially as it’s not immediately clear in the novel’s chronology that the girl was murdered.

“But,’’ the author says, “it was the area of Darian’s loss — his dad abandoning him at a young age — and the man who stepped into that role, Copeland, the elderly police commissioner, that kept me focused as I wrote.”

While Cavanaugh started in the thrall of hard-boiled American writers such as Robert Crais and Dennis Lehane — his prose as sharp and unpredictable as his villains — he’s since marked a dark space for himself alongside the British hard men like Derek Raymond, Ian Rankin and Ken Bruen, writers who refuse to let you sleep easily.

Nor does Peter Doyle, friends, so do yourself a favour and catch up with one of the finest and most entertaining writers this country has produced, his hipster crime novels having already won three Ned Kelly Awards. In 1996 his first novel, Get Rich Quick, Doyle gave us a brilliantly executed shadow history of Sydney in the 1950s, that good time of Tivoli showgirls, jive-dance entrepreneurs and mad reffos fighting for causes no one could remember. Amaze Your Friends (1998) continued the increasingly desperate adventures of Billy Glasheen, lurk merchant and low-life, as the past caught up with him in the form of Fred Slaney, Sydney’s meanest, crookedest cop.

The Devil’s Jump (2001) was more of a jive, reefer and zoot-suit affair, presenting with a tent show’s raucous flair the inside dope on Billy’s guttersnipe early days, chasing the big payday through the delirious confusion of postwar Sydney. In a permanent state of combined boredom and terror, Billy mooched through these novels, the stalled love affairs, plummeting expectations and shady detours, straight out of your 50s paperback private eye yarns.

Now he is back in The Big Whatever (Dark Passage, 308pp, $24.95), along with some of Doyle’s other recurring characters, including the frightening Slaney. It’s 1973 and Billy, older and maybe wiser, is pushing a cab on the night shift, moving hot transistor radios and deals of pot on the side. Mostly he’s brooding about bad luck and betrayal. Then he finds a beat-up paperback entitled “Lost Highway to Hell” along with a Carter Brown dime novel in the taxi. He starts reading. It seems to be about him: the cloak-and-dagger, the needless complications, the misdirections, the blurry divide between truth and fantasy.

He can’t think who could’ve written it other than Max Perkal, legendary Kerouacian hipster, long-time ivory tickler and string picker and his old partner in crime who doublecrossed him and left him in the mess he’s in. Only Max is dead. He went up in flames in a fiery Hume Highway inferno after a police shootout, part of the so-called Hippie Gang, along with lots of cash, following a bank heist. But if Max is alive, Billy has a score to settle.

“There’s a whole book-within-the-book thing. Kind of an alternative history to the alternative history,” Doyle says. “Lairy stuff, huh?” Indeed it is, created with the kind of energy taxi drivers such as Billy call “running hot”, when you don’t stop for a drink or a stretch for fear of breaking the thread of where you are going. This series is a wonderful example of what Stephen Knight in his superb study of local crime fiction Continents of Mystery called the modern version of “the criminal saga”, a form specific to this country, of the self-expressive aggression of the colonised underclass.

This is the most entertaining novel you’ll read all year, a thriller that, winking at the world, can only make you smile. Robert G. Barrett was a master of the form but Doyle is the king, his books steeped in a witty instinctive hostility to all authority, and to borrow a phrase from Knight, consistently lurid and leering, and completely original in voice.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout