Cressida Campbell’s frightening diagnosis

Just as Cressida Campbell’s star was soaring, she began suffering odd sensations and headaches. This is the story of how one of Australia’s most successful artists overcame the most terrifying experience of her life.

Two years ago, Cressida Campbell was in hospital in Sydney and the doctors didn’t know what was wrong with her. For several weeks, she’d been having odd sensations, headaches and occasional mishaps. Fearing the worst, she’d started self-diagnosis on the internet, looking up motor neurone disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke.

Now she was in hospital and confronting her deepest fear. Her neurologist had handed her a fountain pen and asked her to draw a star.

“At first I didn’t know what the pen was,” Campbell says. “It had affected your perception. I didn’t know how to pick it up or anything.”

She picked up the pen, and all she could manage was to draw a formless squiggle.

“That was the only time I burst into tears,” she says. “I wouldn’t have been able to paint again, because I’m right-handed. It was a terrible moment of realisation. I didn’t realise I was paralysed.”

The experience was devastating for Campbell, 62, whose work relies on incredibly fine motor skills. She is a singular artist. For more than four decades she has worked almost exclusively in the slightly arcane and time-consuming medium of woodblock printing. The term sounds crude or mechanical, but in practice the work is highly detailed and intricate, artistic decisions being made at every moment.

Collectors adore her, and demand frequently outstrips supply. A recent show with her commercial gallery, Philip Bacon Galleries in Brisbane, was fully sold. Next month, and for the benefit of her less moneyed admirers, Campbell’s work will be shown in a major retrospective at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. It is possibly the biggest honour of her career.

But for several weeks in 2020, she feared she may not paint again. Her specialists at St Vincent’s Hospital eventually diagnosed a brain abscess, a rare condition caused when an infection gets into the grey matter and forms something like a boil. Campbell says it was detected as being about the size of an olive, and that when it was removed, it had grown to the size of a lemon.

![“Most infections don’t get through the brain’s blood barrier,” she says. “[There’s] one in a million chance of getting it.” Picture: Jane Dempster/The Australian.](https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/59f7892311fdcc60cebf6266130947c4?width=650)

It’s typical of Campbell’s conversation that she’s able to relate the horror of this story with something approaching humour. I’ve arrived at her house in Sydney’s eastern suburbs on a Sunday afternoon. When she opens the door, she immediately apologises for being in her studio clothes – a comfortable green jumper and printed cotton pants. Her wavy auburn hair seems to have a life of its own. She’s trying to finish a painting for the NGA show, and would I mind if she works while we talk?

“They never found out why I got that brain abscess,” she continues. “Most infections don’t get through the brain’s blood barrier. One in a million chance of getting it. And consequently, they’re not easy to diagnose because not many people get them.”

Campbell’s studio is in a separate building behind the house. Dominating the room is an American-made easel – a towering structure with a counterweight that Campbell calls her guillotine. A table is strewn with half-squeezed watercolour tubes and spent sable brushes. There are three radios (one of them broken), a cordless telephone, a clock, and an airconditioner that has thankfully taken the chill off the air. While we talk, her cat, a handsome Russian blue called Minski, comes and settles on my lap.

Campbell has applied her woodblock technique to a variety of subjects, from early pictures of Sydney Harbour as a working port, to landscapes of the bush around the city, and still-life subjects such as plump persimmons, banksias and hydrangea blossoms. More recently she has focused on the interior of her own home, with its elegant display of framed pictures, carved chairs and ceramic bowls, along with more mundane items like the ironing board.

The woodblock she’s working on at present is called Night Studio (at least that’s how it’s listed in the exhibition catalogue, with the note “work in progress at time of printing”). It’s a scene of the studio in which we’re sitting.

The long vertical picture will show a set of louvre windows, whose individual panes and areas of overlap form a series of horizontal stripes. The windows allow a partial, darkened view of the plants outside, and also a fuzzy light which could be a street light or, more romantically, the moon. (“It’s a street light,” Campbell says.)

In the picture, the blackness of the glass will reflect the studio back to itself, including the clock and the scaffold-like structure of the easel. On the table is the air-pressurised burr that Campbell uses to carve her compositions into the woodblock. She remarks that her brain surgeon used a similar device – presumably one of medical grade – to drill into her skull and remove the abscess.

Campbell says her methods have so often been described that people will think it’s boring to read them again in print. Still, the painstaking process is one aspect of what makes her work unique.

She first draws her composition in pencil directly onto the woodblock – actually a thin piece of plywood – and then uses the burr to cut the outlines and textural details into the soft timber. She paints watercolour onto the plywood, staying within the incised lines. This is the stage she’s at on the Night Studio painting, and during the hour or so that we spend talking, she’ll complete an area of about 5sq cm, painting the dull-green colour of oleander leaves.

The next stage is the trickiest. Using a light water spray, she dampens the painted plywood surface, uses art paper to make an impression, and very gently peels the paper away. This is the process that produces the characteristically mottled or “fresco-y” texture. The print is always touched up in watercolour to produce a finished picture.

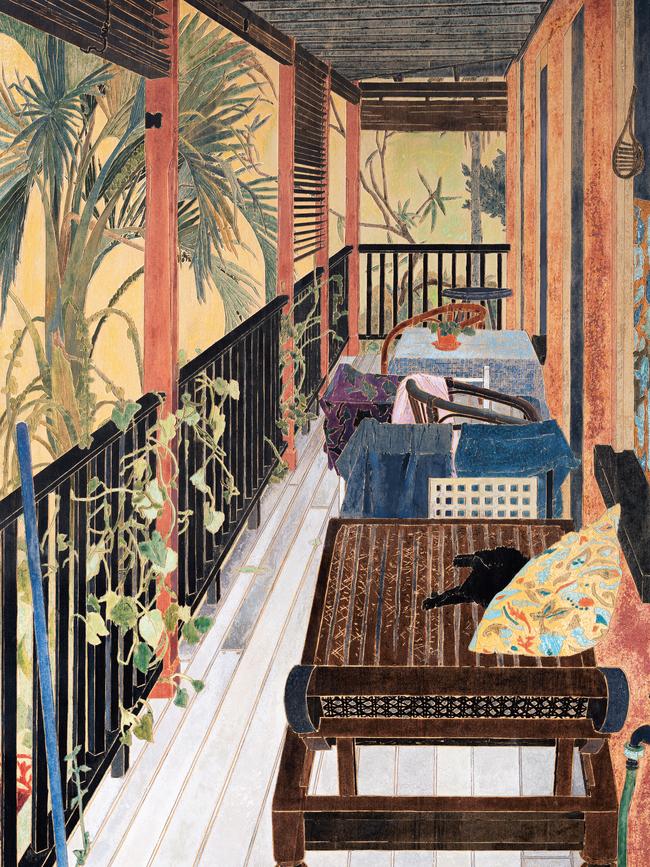

Both the original woodblock and the one-off print are individual works of art and are sold as such. In the Philip Bacon Galleries show, the larger pieces were selling for $420,000. An early work by Campbell called The Verandah, dated 1987, recently came up for auction and sold for $515,454 including buyer’s premium. Owned by a private collector, it will be in the NGA retrospective.

“Anyone could learn this technique, although no one wants to do it because it is so laborious,” Campbell says. “The printing is difficult, and also a lot of people would just prefer to paint straight onto canvas. But I like the progression – of drawing, carving. I like doing everything separately, whereas a lot of people want to do it all at once. It’s not a criticism, it’s just a different way of thinking.

“When I’m carving, I’m thinking about the picture, thinking about what colours I’m going to use, and how I’m going to bring it out. And then painting, I like the way you just concentrate on the colour. It’s a combination of a lot of different things.”

The NGA exhibition is comprehensive and large, with more than 130 of Campbell’s works. It includes some of her paintings from childhood and her early 20s – such as her striking self-portraits done in acrylic on canvas – but focuses on the four decades since her first main show of woodblocks in 1985.

Her early woodblocks have a stronger sense of graphic art than her later, more painterly work. She takes great care to compose her pictures, and while they may appear to be scenes from everyday life, the objects depicted are not randomly chosen but thoughtfully arranged. She’s always been attracted to the details of domestic life: a coffee percolator on the stove, the washed dishes on the rack, even the compost bin.

Curator Sarina Noordhuis-Fairfax has arranged the exhibition across six themes – still life, interiors, plants, studio, bushland and water views – so that a variety of subjects are explored across a career that is remarkable for its consistency and ever-deepening mastery of medium.

“Although there are obvious differences in my work as you go along, from being very young, it’s not as though it’s changed unbelievably,” Campbell says. “It’s not like I went from painting apples to total abstractions. But what is obvious is that I’ve gone back to different topics time and again.”

When she was starting out, Campbell often became friendly with people who bought her pictures, or at least she knew them. More recently, as her prices have pushed into the hundreds of thousands, she knows some of the buyers, but not all. The exhibition has relied on loans from other public galleries, but many have come from private collectors. She says Noordhuis-Fairfax and Lachlan Henderson, Philip Bacon’s gallery manager, have been tireless in tracking down works for the exhibition. Only a few that she would like to have included – such as a picture of paperbark trees in Sydney’s Centennial Park – couldn’t be found or the request for loan was declined.

The exhibition will include some works by other artists Campbell loves or has an affinity with. Margaret Preston’s woodblocks were a revelation to Campbell when they were shown at the Art Gallery of NSW in 1980. She also admires the delicate, white ochre paintings of Dhalwangu-Narrkala artist Djirrirra Wunungmurra from northeast Arnhem Land, and Melbourne modernist John Brack for his scenes of everyday life and quirky domestic details. The tradition of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock printing is represented with work by 18th-century artist Kitagawa Utamaro.

Several of Campbell’s paintings from the past few years are intimate depictions of rooms in her house. Indeed, visiting her feels like walking into a Cressida Campbell painting, where the living room is lined with prints and paintings, ceramic bowls are arranged on shelves, and there are vases of flowers and palm fronds.

A new piece from the Philip Bacon show that has been acquired by the NGA, called Bedroom Nocturne, is a tondo or circular painted woodblock of Campbell’s bedroom. Bedclothes are strewn on the bed. On the wall are a large painting by Wunungmurra, an ochre painting by Queenie McKenzie, a scene of smokestacks by Paul Ryan and other pictures. It’s dark outside, as can be seen through the half-open shutters, but the room is illuminated by a ricepaper lamp on the bedside table. In the exhibition catalogue, Campbell says the circular composition creates a kind of voyeuristic peephole. And the peeper may ask themselves: has someone got out of bed and left the room, or are they about to walk into it?

Earlier this year, Campbell married her partner of several years, photographer and printmaker Warren Macris. He had proposed to her in 2020, days before she started to become ill with the brain abscess. She has also suffered her share of sadness. Her first husband, film writer Peter Crayford, died from cancer in 2011. Her beloved mother Ruth died in 2018, at 95. Then her brother Patrick Campbell, a pioneer in solar energy research, died after being diagnosed with leukaemia in 2020. And her own health battles have not left her unscarred. The brain abscess, or the surgery, has caused her to have seizures, and she will be taking epilepsy medication for the rest of her life.

Campbell is reluctant to offer a commentary on her work, but the interior scenes of her home do offer a kind of autobiography, at least superficially – a picture of comfortable living, of the pleasure taken in fine art and furnishings. Anything else is speculation and suggestiveness, but Campbell offers an insight when she says that the interiors with darkened windows and reflections corresponded with her mourning after Crayford’s death. “I did spend a lot of time lying on the sofa, looking at the reflections, thinking how …” she begins. “I just like the look of it.”

Minski has chosen this moment, late in the afternoon, to get up from my lap, climb onto Campbell’s table, and take his place among the paint tubes and brushes. He has strikingly broad features, intense blue eyes and an enigmatic smile. It’s as good a time as any to ask Campbell what her pictures mean.

“That is a tricky question,” she begins. “I was talking to a friend yesterday, who I haven’t spoken to for ages. He said, ‘Darling, just do what Maria Callas did. She said listen to the music’. And if I wanted to be rather avoiding the question, I’d say just look at the pictures. And in many respects that is the best answer.

“To me they are abstract in a way that I’m trying to just make the colours and the design as powerful to the eye, and interesting to the eye, as you can get it. It’s about the colour, the design, the mood, everything. But at the same time, you can’t ignore the choice of a subject.”

Perhaps it’s best, after all, to accept Campbell’s advice and enjoy her pictures for what they are, a mystery wrapped in pure aesthetic pleasure.

Cressida Campbell is at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, September 24-February 19.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout