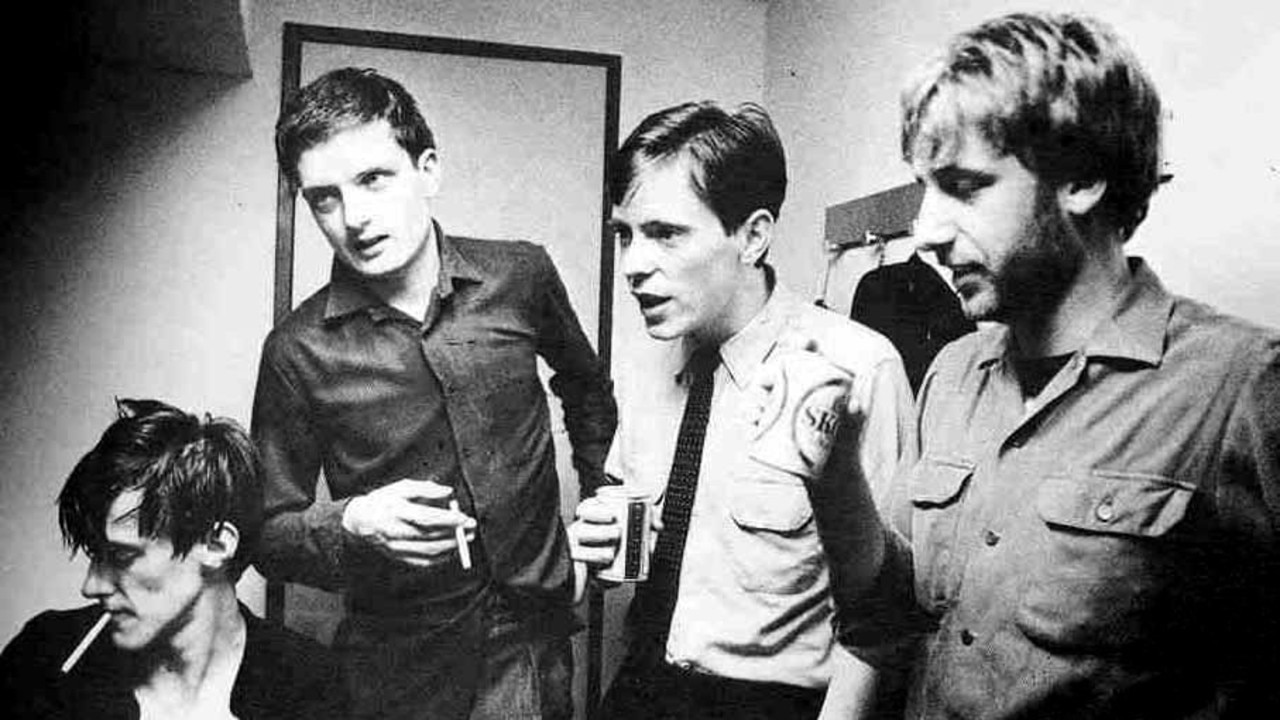

Creative partners

Deborah Conway and Willy Zygier were smitten the first time they met.

Willy Zygier

We spoke on the phone first. Deborah was looking for a guitar player for the String of Pearls album tour in 1991. I said, “Look, I can’t do the tour — I’ve got a gig I really want to do and it clashes.” This was a single show getting in the way of a six-month tour she was offering me. Deb got off the phone and went, “Who the f..k is this guy?”

She put off her tour, then rang me back a week later. I went to her place and it was one of those crazy things: she opened the door and I felt a bolt of electricity. That first meeting was extraordinary. It was a big surprise for me to have such a visceral response to a human being. I’d say it had never happened before, or since.

There was definitely a spark of attraction but also a spark of intrigue. I thought: “Wow, you’re one hell of an interesting person. I’ve never met anyone like you before.” Deborah’s a very forthright, no-holds-barred kind of person. She’s a great one for the truth, whether you want to hear it or not. The strength of her character was immediately apparent. Most people like to hold back and not say exactly what they think. Deborah is totally unlike that.

I knew she was a successful musician but I’d always been the sort of person not so interested in what was going on in the charts. Obviously I’d heard Man Overboard, which was part of the culture, but I didn’t know much about Deborah or [her earlier band] Do Re Mi. I’d always been involved in obscure arty music, little projects; mutual musician friends connected us.

The attraction was an annoyance in a way because I was in a relationship at the time. It was definitely not something I was looking for or wanted to feel. It was just one of those times in life where you’re not quite in control.

I do remember the first rehearsal, which we started by playing Release Me, the first song from String of Pearls, and it sounded amazing. It was like all the stars were in alignment; it just sounded incredible, which I could see in the look on everybody’s faces.

Deborah was at the height of her fame and popularity, and we were playing five or six nights a week for six months to sold-out crowds at a mixture of clubs and theatres. It was an extraordinary time. No one can play like that these days.

I’d started my relationship with Deborah and she was over one night. I said: “Look, I’ve got this bit of music, do you want to hear it?” I la-la’d through what became the song Now That We’re Apart, on Bitch Epic. Deborah said: “I really like it, and I’d like to write some lyrics” — which is what I was hoping she’d say.

As we came together the two other relationships were breaking up, so that’s why that song came about. It was an amazing time to be falling in love, but also a terrible time. Twenty-eight years, three children and 10 albums later, I still feel guilty.

I think she’s got a great instrument, although she worries about her voice as she’s gotten older. I think her instrument has gotten richer and more expressive and she’s able to have more dimensions in the music. I think when you’re young and you write a song, there’s this beautiful sense of having carved something out of nothing whereas now, getting older, I need to know that song has some intrinsic value for me as a piece of art, as something I feel is worth saying. There are millions of songs in the world; they’re a common form of art. It’s fine just to write another song for the world but it’s not something I particularly want to do any more unless I feel the need to do it.

In bringing up our children, Deborah almost had a more masculine role and I had a more feminine role: I was more the cautious one worrying about the children, whereas Deborah would say, “Come on, let them get out there and do it!” We probably slightly inverted the traditional roles, and still do to a certain extent. It still makes for a good team.

Both of us really respect each other and listen to each other, and even though we are different as human beings, we really complement each other. That tips over into most aspects of life. We have tiffs about things and shit each other sometimes — but as far as human couples go I think we’ve done a damn good job of it. We’re pretty lucky to have found each other.

-

Deborah Conway

When he came around to my St Kilda flat and I opened the door, and both of us took that step backward. He was a dark and fascinating man. He’d been talked up by these two friends of mine, who were both fine guitarists themselves. I was very curious. I hadn’t seen or heard him play but his reputation preceded him.

Willy and I stared at each other for that whole rehearsal period. The attraction and chemistry was very strong. There was something very clear about it, right at the very start. By the end of that tour, my memory is that we were in Queensland, and the last date was in Coolangatta. We both had a little dance in the regional airport lounge. We were proper adulterers at that point; terrible people.

We both realised that we wanted to be together, but there was trouble coming, and it was going to be awful for everyone and take a while to see it through, and for everybody to be OK. My partner was coming out from America on a visit, and (Willy) was going to have to deliver the news to his partner. None of it was nice. It was awful.

It was very tough for me, as my partner and I had been together for five years, but he was overseas, so we’d been separated by distance for quite some time. It was even harder for Willy. He and his then partner were living together in Melbourne. That first relationship is still based on love, loyalty and care. The last thing you want to do is tear that person up, but it’s dishonest not to. It’s ghastly. I would never wish it on my worst enemy.

The first song that we wrote together was a reflection on what we’d just put everybody through. It was a fairly dark piece. I thought it was a good tune, and it went to interesting places. We knew that we were going to do that: he was a songwriter and I was a songwriter. We wanted to put that together. He was happy to have his fortunes in with mine, and vice versa.

It took me a long time to put his name on the records, but we were together from Bitch Epic. There were still some songs I’d written alone, but with everything we did, it was becoming more obvious that it was a good partnership.

It’s a big thing to give someone criticism, as people don’t like to be criticised. Maybe it’s easier when you know you love someone and trust them, and you’re eating breakfast and going to bed together at night. But you don’t have to be a couple to do that; to have a strong bond together is perhaps the best way to be able to be brutal. It’s really the only way to make the best work.

Everything else is just fluff; it’s just blowing smoke up someone’s arse. If I tell you what I really think, you’re probably going to turn around and be furious. You have to be brave to tell someone what you really think, and then be open to experiment to take on someone else’s advice.

As someone being criticised, you need to understand it’s not you that’s being brutalised, it’s the work, and to pare that away from yourself. It’s really hard. I arc up too: “What do you mean you don’t like that! I’ve been working on it all morning!” But that’s the creative process. If you can not explode, but take a deep breath and think, “Wait a minute, maybe they’ve got something here …” If you cogitate on it for a day or two, then come back and do it better — god, that feels good.

He’s a beautiful father. Our three girls adore him because he’s endlessly patient and so much fun. We’ve been absolutely in lock-step all the way with how we parent. When I was going away and doing the Patsy Cline shows or working as the artistic director of the Queensland Music Festival, he stayed home looking after the babies. It was definitely a reversal of roles, with him changing the nappies and cleaning up midnight vomits, but he never lost his sense of humour through it all.

We thought, “They’ve got two musical parents, it’s in the house all the time — wouldn’t it be wonderful if they had a good basis to build on?” So we gave the girls piano lessons from the age of four, which meant we were sitting beside them for the first few years while they plonked out tunes and we sang along with the kids.

We had to push them to get them through the early years, but in the end they’ve made their own choices. They’ve all gone with performance careers at this point, and they’re very strong singers. I love performing with them, but it’s beautiful for us to watch them, too. It makes me very happy. Willy is a wonderful life partner. I couldn’t want for any more.

After our interview, Conway sends this text message:

Willy Zygier is a constantly inventive musician. His jazz roots ground him in the vernacular of real-time composition which makes every show we’ve ever played a little bit different from the last. He’s always surprising, and 99.9 per cent of the time it’s a really good surprise.

Deborah Conway and Willy Zygier will perform their newest album, The Words of Men, and their first collaboration, Bitch Epic, on a national tour that begins in Perth on May 23 and ends in Mackay on June 30.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout