Coronavirus will cause ‘irreparable damage to arts industry’: expert

As star Tom Hanks is added to the growing list of cultural casualties, the industry is reeling from a wave of cancellations.

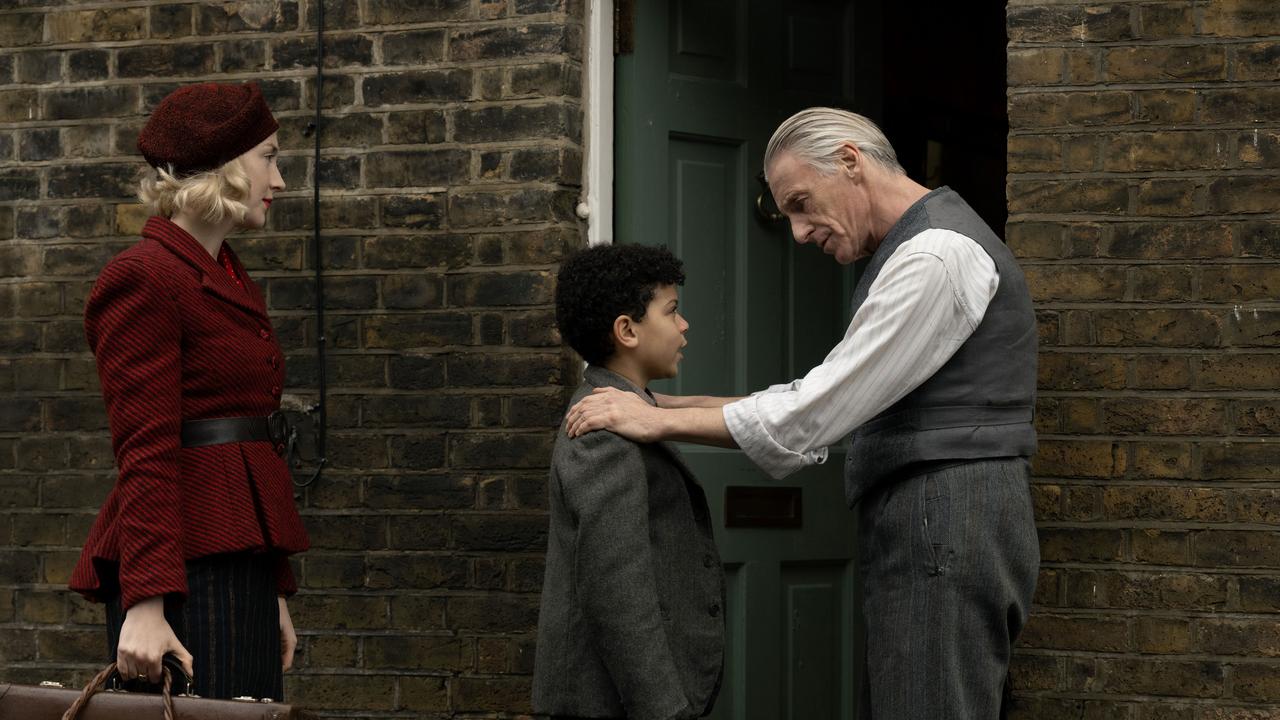

Australian theatre producers the Michael Cassel Group were always going to be on to a winner with their Melbourne production of the musical, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, given the built-in, ardent fan base for JK Rowling’s novels.

The Victorian capital was only the third city in the world, after London and New York, to host the show, and the Melbourne production celebrated its first birthday this month, having played to more than 300,000 Potter tragics and their kids. The two-part show, which picks up the narrative thread 19 years after the last Potter novel, is taking bookings through to September, and Cassel Group’s Remy Chancerel says: “Harry’s going very well.’’

There is no hint of self-congratulation or triumphalism in Chancerel’s voice, however. For while Harry, Hermione, Ron and their fictional offspring are providing box-office magic, the coronavirus has cast a pall over another big-budget, family-friendly show produced by the Cassel company — the international touring production of Disney’s The Lion King. The Australian company has successfully co-produced and toured this blockbuster to Manila, Singapore, Korea, Bangkok and Hong Kong.

It was due to premiere — ominously, as it turns out — in Wuhan, China, in February, before transferring to Beijing. As most readers know, the coronavirus epidemic is thought to have started in Wuhan and that city has been locked down for weeks, so The Lion King has been “indefinitely postponed”, says Chancerel. “As the nature of the tour evolves, and so does the coronavirus, we don’t know when we can come back,” he says. The Beijing season is due to start in May, but its future is uncertain, too. Chancerel tells Review the company’s founder, Michael Cassel, is in talks with his Chinese partners and that Beijing “is part of the conversation”.

The grave doubts about The Lion King’s China season are part of a bigger, accelerating trend of virus-related cancellations and postponements that is roiling the performing arts, film and music sector here and overseas. On Friday, the world’s biggest art gallery, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, temporarily closed its three venues in the city, while Broadway theatres and the Metropolitan Opera were effectively shut down by a ban on gatherings of more than 500 people across New York State, which was introduced in an attempt to slow the spread of the virus.

Disneyland in California is to close its doors from this weekend, following a surge of coronavirus cases in that state, while the Smithsonian museums in Washington, and Amsterdam’s Van Gogh museum and Rijksmuseum have closed until the end of this month.

Amid predictions that Hollywood studios are facing potential billion-dollar losses and that the economic fallout from virus-related hits to local culture events could be “massive”, a sense of anxiety and uncertainty pervades the industry. This only intensified on Thursday, when Hollywood star Tom Hanks revealed he and his wife, singer Rita Wilson, had tested positive for coronavirus while in Australia.

The 63-year-old dual Academy Award winner had been working on an as-yet untitled Elvis Presley biopic with director Baz Luhrmann on the Gold Coast. Wilson had recently performed concerts at Brisbane’s South Bank and at the Sydney Opera House, and Channel 9 staff who were involved in an interview with her on Monday have self-isolated. Hanks said on social media: “We Hanks will be tested, observed and isolated for as long as public health and safety requires.”

The star’s revelation ricocheted around the world’s media outlets and websites within minutes, and added to the growing list of cultural casualties as the performing arts, music and film businesses grapple with this unprecedented pandemic. Over the past eight days alone, composer Brett Dean pulled out of an Adelaide Festival concert after he contracted the virus; UK comedian Russell Brand cancelled his Perth show; and US pop star Miley Cyrus withdrew from her headlining gig at a bushfire charity concert in Melbourne, which was then cancelled.

On Wednesday, the world’s biggest-grossing music festival, Coachella, due to open in California in April, was postponed for six months; this followed the cancellation of Austin’s South by Southwest Festival of music, technology and film, a move which is predicted to cost the Texas economy about $US300m ($466m). On Thursday, US alternative rock band Pixies postponed the remaining Brisbane, Sydney and Perth shows on their Australian tour, “out of caution for current public health concerns”. They promised fans’ tickets would be “honoured” at rescheduled concerts later this year.

In a further postponement, the Australian release date for Sony Pictures film Peter Rabbit, starring Rose Byrne and Margot Robbie, was pushed out from March 22 to September. This delay followed last week’s announcement that one of 2020’s biggest movie releases, Daniel Craig’s last James Bond film, No Time to Die, has been punted from April to November, reflecting how the coronavirus has closed cinemas or cruelled attendances in several of Hollywood’s key international markets.

Also making headlines this week was the decision by David Walsh, the mercurial professional gambler behind Tasmania’s Museum of Old and New Art, to cancel Hobart’s closely aligned, midwinter festival, Dark Mofo, because he feared the hefty financial losses that could flow from any last-minute cancellation: “The (Tasmanian) government and MONA are each on the hook for $2m to run Dark Mofo,” Walsh said in a statement. “That’s bad. What’s worse, as far as I’m concerned, is that if we ran Dark and nobody came, I’d lose $5m or more.” Walsh said colleague Leigh Carmichael, who oversees Dark Mofo, predicted the losses from a virus-related cancellation could reach $8m. In his inimitable style, Walsh said “that kind of blowout would affect MONA’s program, and I’d be back to subsisting on the diet I had when I was 18 — pineapples and mint slice biscuits”.

Walsh, MONA and Dark Mofo have spurred a tourism revival in Tasmania, so the decision to cancel — even though there are just three diagnosed cases of coronavirus in Tasmania — will be a blow to that industry. Walsh admitted: “We’re killing Dark Mofo for the year. I know that will murder an already massacred tourism environment.’’

Meanwhile, on Thursday, Sydney Writers’ Festival artistic director Michaela McGuire and CEO Chrissy Sharp found themselves launching their 2020 program “on the same day that the World Health Organisation has declared the novel coronavirus (a global pandemic)”. The festival, held in May, is one of the biggest events of its type in the world. It sold more than 52,000 tickets to its paid sessions last year, and its leaders stressed in a joint statement that the “health and safety of authors, publishers, audiences, staff, volunteers and all attendees is Sydney Writers’ Festival’s first and foremost priority. We have noted the cancellation of a number of international literary and public events over the last few weeks”.

They said the virus situation was “developing rapidly”, and that they were following official health advice, adding: “As the festival is still more than six weeks away, we are cautiously proceeding, but recognise that it’s a concerning time for everyone, and that we need to adapt accordingly.”

Booker Prize co-winner Bernardine Evaristo headlines the festival’s line-up, which features hundreds of local and overseas authors and explores the theme, Almost Midnight, a reference to the Doomsday Clock and the threats posed by climate change, nuclear weapons and cyber misinformation campaigns.

However, as the McGuire-Sharp statement suggests, it may be a different kind of threat — the viral pandemic — that could see this year’s event unravel. Review understands the festival’s board is working on a contingency plan that could involve cancellation, should the public health threat intensify.

Despite the string of cancellations and postponements, as Review went to press, most Australian festivals, performing arts companies, museums and galleries were open for business — albeit with many providing patrons with hand sanitiser and conducting extra cleaning of venues. However, Evelyn Richardson, chief executive of industry group Live Performance Australia, says the rising number of delays, cancellations and possible venue closures “will cause irreparable damage to our industry … We think the flow-on effects could be massive, both for our industry and the broader context of the economy.”

Asked whether any arts companies are likely to go under, she says: “We are very concerned there is fragility in the sector.” This financial fragility, says Richardson, applies to the subsidised and commercial sectors and to large and small companies, which are all grappling with multiple challenges: the spectre of cancellations and closures, hits to box-office takings and the need to meet already contracted costs. Some subsidised companies were also facing uncertainty over whether their Australia Council funding would be renewed, while others were still dealing with fallout from the summer’s devastating bushfires.

Richardson points out the Australian live performance industry is a $2.5bn-a-year sector that employs 34,000 people, supports more than 500 performing arts companies and hundreds more venues, producers, music promoters and festivals. “We will need government assistance to keep these businesses operating,” she says, adding that “there are a lot of businesses around our companies that are impacted as well”. These include restaurants, cafes, hotels and regional tourism businesses.

LPA has written to federal Arts Minister Paul Fletcher “urging the government to consider measures which would underpin short- and longer-term confidence for the industry and minimise the loss of income, jobs and investment”. She says the live performance sector is operating “in an environment that is volatile and changing daily”. She adds: “We are watching the situation very closely. We are very much being guided by the advice from the state and federal health authorities, which at this stage continues to be a ‘business as usual’ approach for events and public gatherings.” However, she says “our industry is very mindful that the spread of coronavirus … could lead to new restrictions being put in place”.

As the virus rampages around the world, there are predictions Hollywood studios could lose millions, even billions of dollars if their big-budget “event” films cannot be shown in coming months in locked-down markets such as China, as such movies earn up to two-thirds of their box-office revenue outside the US. In January, China — the world’s second-biggest box-office market — closed down its 70,000 cinema screens.

According to the Vulture website, “Hollywood is facing a doomsday scenario of its own: the cancellation of blockbuster-movie season” in the northern spring and summer, as viral panic spreads. The shuttering of cinemas in China and dwindling cinema attendances in other virus-hit nations such as Japan, Korea and Italy has already seen big-budget film F9 (from the Fast & Furious franchise) delayed, along with No Time to Die and the dystopian thriller A Quiet Place 2. “Some analysts,” said Vulture, “believe coronavirus could result in a loss of at least $US5bn from diminished box-office returns and impacted production across the film industry.”

Back home, the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra is still reeling from the effects of the summer bushfires and must now overcome another setback, as viral cases and concerns grow. In January and February, interstate tourists stayed away from the National Gallery of Australia’s $5m Matisse and Picasso blockbuster, because of the bushfire crisis and the thick smoke that wreathed Canberra — visitor numbers for those months were a whopping 60 per cent below expectations.

The blockbuster was five years in the making, and explores the rivalry between the two European painting masters. In a candid interview, NGA director Nick Mitzevich tells Review that “our January and February tickets (for Matisse and Picasso) were 60 per cent below where they needed to be, but the last two weeks we’ve seen an improvement”. Still, he says, visitor numbers would “probably need to be doubled” in coming weeks, if they were to make up for those earlier “hits”. He says: “We had quite a horror summer with the smoke in Canberra, so our (corporate) event bookings took a bit of a beating there, as well as our tickets to Matisse and Picasso. In the last couple of weeks there’s been a recovery in our ticket sales to Matisse and Picasso, but we haven’t seen a recovery in our event bookings and I think the effect of corona has yet to be seen on our tickets, so we’re very cautious about March and April.”

The clearly worried gallery director says the summer of fire and smoke, combined with the coronavirus threat, has “really rocked people’s confidence in travelling”. This negatively impacts the NGA, “because nearly 80 per cent of our visitors come from interstate”.

The Matisse/Picasso show runs until April 13, “and the jury’s really out on where it (the virus contagion and visitor trends) will go”, Mitzevich says. “We’re really hoping to get a great boost in the last couple of weeks of Easter and the school holidays. It’s an extraordinary show,” he says.

He also explains that for the NGA, “the ramifications (of the virus) are much broader than people just walking through the door”. So far, the institution has cancelled international travel for research staff, and suspended visits to its archival library by overseas researchers. Even with these precautions, Mitzevich says the unfurling corona crisis “is a waiting game and we’re just poised to respond as things change”.

Overseas galleries and theatres have also been caught up in the global pandemic. According to the ARTnews website, the National Art Museum of China in Beijing and the Union Art Museum in Wuhan are closed indefinitely, while some of Japan’s most popular museums are to remain closed until mid-March, among them Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum and the Kyoto National Museum.

In Paris, the Louvre, the world’s most visited museum, is restricting entry to online ticket buyers and people who are entitled to free admission, after closing for two days last week due to staff concerns about the virus. France and Switzerland have banned gatherings of more than 1000 people and, overwhelmed by the biggest virus death toll outside China, Italy’s entire population is locked down. The Zurich Opera House seats more than 1100 people, and its management has manoeuvred around the new restrictions by limiting audiences to 900 patrons.

Interestingly, organisers of the Cannes Festival, the world’s most prestigious film showcase, were still pushing this week towards their May 12 opening date.

British comedian Brand was scheduled to perform his sold-out show on Monday night at the Perth Concert Hall — the same venue visited by a coronavirus sufferer two nights earlier. Just hours before curtain up, Brand tweeted that the show would be cancelled, as he was “not happy with the risk for me or for any of you (fans)” at the venue.

Brand’s fans were divided: Some said the cancellation was sensible, while others saw it as an overreaction — West Australian health authorities had not asked for the concert hall to be closed. (The coronavirus carrier had been overseas and attended a Western Australian Symphony Orchestra concert last Saturday night — testing positive to the virus that same night.)

Despite Brand’s refusal to perform in Perth, an orchestra spokeswoman tells Review: “Ticket sales (for WASO) have not been affected since the announcement of the COVID-19 case … Perth Concert Hall is open for business as usual. The venue has been fully cleaned in line with government guidelines, and all performances are proceeding as scheduled.”

Three days before Brand cancelled, it was announced Australian composer Dean had contracted the virus and would be unable to conduct a Beethoven concert featuring the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra at the Adelaide Festival. A video of Dean, who recently travelled through Taiwan and was being treated in hospital, was played at the start of Saturday night’s concert and a festival spokeswoman says it “was really well received”.

Fans of that festival and world music festival Womadelaide were not deterred by virus concerns: As artists, singers and bands from around the world took to stages small and large in the City of Churches, the festival exceeded its box-office target, while Womadelaide attracted almost 100,000 people.

Although it is less exposed to the pandemic than live performance companies, the literary scene has not been immune. Publishers reported supply chain disruptions in January and early February while Chinese printing factories were closed, though many have since reopened. Last week, one of the world’s biggest commercial literary events, the London Book Fair, which attracts about 25,000 publishers, authors and agents, was cancelled.

Denny Neave, managing director of independent publisher Big Sky, says printing delays in China in January and February delayed the release of about 10 of his press’s titles by one month. “It does have a knock-on effect for us financially (but) more worrying for us is the downturn in foot traffic through the trade (book shops) here,” says Neave. A spokeswoman for Hachette, one of the majors, concurs that “booksellers are really doing it tough right now”, but is hopeful readers who are avoiding shopping centres will buy books online.

Opera Australia has a lot riding on its blockbuster, La Traviata on Sydney Harbour, which opens later this month. In recent years, the multimillion-dollar Handa operas on the harbour have become a tourism and cultural fixture in the NSW capital, with performers arriving by speedboat, finale fireworks and a stunning city skyline backdrop.

An OA spokeswoman says the company has drawn up “a risk management plan” for the Handa opera and the company’s Sydney Opera House performances. She says: “Along with our partners, we are monitoring the situation closely. This plan is being constantly reassessed in accordance with government advice and health authority guidelines.”

Elsewhere, leading arts companies are taking precautionary steps, including extra cleaning of venues. Sydney Theatre Company says it has “taken active steps to brief our staff on this matter, to increase venue cleaning frequency … and have made hospital-grade hand sanitiser accessible to all staff and visitors. Sydney Opera House have taken similar precautionary measures”.

So far, STC has not seen any slowdown in ticket sales because of the virus, though in a statement it spelled out its policy on ticket refunds, making clear that “refunds will not be issued for discretionary non-attendance”. However, refund or ticket exchange requests backed by written medical advice would be approved.

The Sydney Opera House says its “performances are proceeding as scheduled unless otherwise advised” and the three-month-long contemporary art extravaganza, the Sydney Biennale, is still opening this weekend, though organisers are closely monitoring the virus situation.

LPA’s Richardson points out that more than 26 million tickets were sold for live performances here in 2018, “generating more than $2bn in revenue, more than all of Australia’s major sporting codes combined”.

She argues that so long as health authorities say it is safe to do so, “it’s essential we keep the doors open and lights on for live performance as much as we can, given our economic and social contribution — including in regional communities which are trying to recover from recent bushfires”.

This article was published shortly before the Federal Government announced its ban on gatherings of more than 500 people, from Monday March 16, 2020. Since the announcement, the 2020 Melbourne International Comedy Festival has been cancelled, while the Sydney Writers Festival suspended ticket sales, and is to make a more detailed response on Monday. The Sydney Biennale is going ahead as planned but “will be monitoring the situation on a daily basis’’, while the National Gallery of Australia said it was seeking advice about the “recent Commonwealth guidance’’ and would be open on Saturday. Live Performance Australia warned that “the flow-on effects of this (ban) on our industry are huge’’.

READ MORE: Coronavirus live, updates