Contemporary Australian Poetry: a mixed bag of delights and dross

There are hits and misses in an ambitious new anthology of contemporary Australian poetry.

Poets used to be like rock stars. Their verse was recited, remembered and regarded as the pinnacle of a writer’s achievement. Now a real rock star in Bob Dylan has won the Nobel Prize in Literature with lyrics that are to poetry as a clay pot is to a golden bowl. Poets now seek succour in the dubious sanctuary of academia and struggle for a dwindling reading audience, like beggars fighting over the contents of a dumpster.

There are a few intrepid small presses that continue to publish Australian poetry, such as Puncher & Wattmann, which has now published a hefty anthology of contemporary Australian poetry edited by four poets, Martin Langford, Judith Beveridge, Judy Johnson and David Musgrave.

The anthology covers the past 25 years. The editors’ stated aim is to prove the past quarter-century has been an exciting period for our poetry. They also speculate that prose written during this time has not been as good.

All poetry anthologies these days are a political act. Geoffrey Lehmann and Robert Gray’s Australian Poetry Since 1788 (2011) was attacked because it didn’t include enough indigenous, female and ethnic writers. It was even savaged because Lehmann had the nerve to be poetry editor of the conservative magazine Quadrant.

The editors of Contemporary Australian Poetry are keenly aware of this and, given the fact academics can put an anthology on a university syllabus, are suitably anxious to appear ideologically correct. They have incorporated ‘‘marginalised voices’’, a ‘‘full range of sexualities’’, migrant voices and ‘‘poets of diverse ethnic heritage’’ who try ‘‘to perceive and articulate the land as an entity in its own right’’ (whatever that means).

Some of the strongest anthologies over the years have generally had one or two editors. This provides an opinionated perspective, one that invites the reader to engage with or dispute choices, knowing the individual tastes of the editor. Four editors seem less a personal approach than that of a committee that has cast its net wide to include 240 poets and more than 500 poems.

There’s a tradition that editors refuse to include their own poetry in an anthology, but the gang of four make a brave choice in deciding to include five pages each of their own poems, which for two of them is overly generous, given that better poets have sometimes only two pages to impress.

And there is a real snag with the 25-year time frame. Older poets, some now dead, are allowed one or two poems, but the problem is these pieces are from the end of their careers and are not their best. So for Bruce Beaver, Vivian Smith, and the great Gwen Harwood, the reader has to make do with some lesser works that don’t hint at their real achievements, though the confronting Bruce Dawe poems dealing with his beloved wife’s death are an anomaly in this respect.

Of course any anthology involves aesthetic choices that can be questioned, but I wonder if the editors’ selections of verse by MTC Cronin and John Tranter are their best ones, especially the latter, whose work can sometimes seem like a toss-off but has remarkable depths.

Then there are those decisions about poets who have been given much too much space. Martin Harrison’s poetry, for example, can be listless and so dull at times as to be soporific. Dorothy Porter’s work seems more humdrum than when it was originally published, and Alan Wearne’s garrulous satires have worn badly (bland extracts don’t help his cause).

A number of pages are devoted to John Kinsella, a poet whose work divides readers. Many of his poems have a sketchy quality, as if he hasn’t thought them through closely enough. This can result in untidy endings, as if he is trying to crassly sum up the poem’s meaning.

But when the editors get it right, the anthology sparkles. The volume begins with Robert Adamson and the opening lines of Creon’s Dream: ‘‘The old hull’s spine shoots out of the mud-flat, / a black crooked finger pointing back to the house.’’ Here in a nutshell is Adamson’s use of precise description, original way of looking at the world and a brooding sense of drama unfolding in nature. He has the enviable ability of combining detail in a seeming discursive narrative that at times achieves a sense of the transcendental.

Some selections reconfirm the significance of poets such Philip Salom and Anthony Lawrence, their poetry having gained in depth and technical confidence. Gig Ryan’s selection shows off her characteristic mix of caustic flippancy that tries to veil intense emotional pain. The choice of Les Murray’s verse is particularly acute. Corniche, The Tin Wash Dish, The Last Hellos: all have a sense of unspeakable dread, whether of poverty, of death or the daily rigours of life. It’s no wonder Murray has to believe in a God, or else he would drown in an existential darkness.

Part of the pleasure of the collection is to come upon poems that engage the reader with their vitality and vividness. Samuel Wagan Watson’s delightful Carefree is one, with its young boys playing around a jetty, ‘‘and us in bare feet all the time / three kids in stonefish-infested mud / playing russian roulette — /one good pair of running shoes between us.’’

Chris Wallace-Crabbe has been an underrated poet for a long time. His persona can sometimes hide behind a bemused attitude, but at his best he’s capable of delightful and evocative lines such as, ‘‘my mother came in on tiptoe / to give me a goodnight kiss / between sandman and nightmare’’.

Meredith Wattison’s verse occasionally loses focus, but when it’s tight she’s a fine writer whose exquisite image ‘‘Garrulous as water running over my hands’’ is exactly right. Jean Kent’s Escaping Domestic Science impresses with its complex and emotional narrative, and Judith Rodriguez’s casually interlocked poems Sayings of my Mother, The Sisters and Mother-in-Law (‘‘Becoming a mother-in-law, / to put on all at once the halo / of a Queen Mother flower-border hat, / a competitive smile and deferential / back-seat tasters in music’’) have a ruefulness that comes only with age.

Some poets have one poem that one wishes was the source for more. Kevin Hart is a frustrating poet. His ‘‘voice’’ can be muted and dense, as if he’s keeping intimacy at bay. Therefore The Dressmaker comes as an attractive revelation. In it he remembers how one sultry Brisbane day he stayed at home from school, supposedly sick, watching his mother sewing, ‘‘… pins in mother’s mouth, her neck / Bent to the Singer’s needle, hands feeding / Bright cloth to the machine’’. One wishes he’d write more personal stuff like this.

The editors acknowledge that almost all of these poems are free verse. It’s obvious some poets can be technically accomplished using it, but there are some poems that are little better than minced prose, and others are crippled by jerky rhythms, clumsy vocabulary and a tin ear.

So it’s no surprise — and a relief — when the poetry of Stephen Edgar leaps out at the reader. His elegant verses have a technical brilliance, matched by the way he masterfully juggles rhyme, rhythm, metre and meaning. There’s a touch of the smart alec to him with his knowing references to literary classics (who’d want to read Daniel Deronda just to understand the reference?), but he so often hits the right note, as in Inarticulate:

But still among your clothes for a little while

In some few fully human scents will issue

The scent of you in the scent you would apply,

And in your purse, imprinted on a tissue,

Your red lips waiting in a folded smile.

The folded smile is a triumph. Edgar is like a suave dude who arrives at a party wearing a tuxedo and carrying an expensive bottle of claret, only to discover the other guests are bogans in board shorts and thongs, sucking on tinnies.

Free verse is not the only thing that defines this collection. Nature poems dominate to a degree that made me feel I was reading an anthology from the 19th century. There are countless generic moons, seas, trees, flowers, shadows, night, fruit, clouds and, of course, angels. One of the most fascinating tropes that defines these selections is that of birds. There are hundreds of mentions of generic birds and bird song, and so many references to specific species that I gave up counting after 40 (magpies, pigeons, pelicans, ibis, eagles, swans, corellas, plovers, ravens right through to wrens). It’s like an avian spotter’s wet dream. Is this obsession with birds something typically Australian?

What truly astonishes me is that most of these poets live and work in the city, many of them as creative writing teachers (who, in turn, perpetuate the cycle of poets who can only make a living working in academia). It’s as if they perversely turn their back on their urban environment, pretending it doesn’t exist in their daily lives, yet it’s been 90 years since the brilliant Kenneth Slessor wrote his marvellous poems about the city.

Thank goodness for Pam Brown. Her poems have a robust energy that the majority of the nature poems lack. It’s as if the city is in thrall to a different rhythm and her short lines have a bounce to them. Wordless is a wry and intriguing description of her taking a train from Sydney Central Station and then a bus home. It’s a series of sharp observations, with the journey itself taking on an epic quality, ending with the lines: ‘‘enter the house / hug you, / my synthetic coat/ squeaks.’’ It’s as if Odysseus has arrived back in Ithaca.

There’s no surprise Australian poets seem afraid or wary of the subject of love and sex. It’s a given in all our art. Maybe it’s a sign of our emotional immaturity, like schoolkids sniggering about sex. Cronin’s The Specifics of Love is one of three poems concerning love, and Michael Farrell’s Making Love (to A Man) is the only one about lust, and is a somewhat funny, disturbing and sexy account of a gay encounter (‘‘I could / be the 400th man in his bed’’). There seems to be no answer to why we continue to avoid such a topic.

The subject that emerges over the length of the anthology as the most significant is the death of fathers. Kim Cheng Boey’s Ahead My Father Moves is an engaging tribute to his emotionally distant father. For Judy Johnson the talisman of her dad’s railway watch is the catalyst for her poignant memories of him. Alan Gould’s One Sunday, David Musgrave’s The Dead (‘For my Father’), Felicity Plunkett’s Learning the Bones, Peter Porter’s My father was a businessman and Kevin Hart’s poem with its cry of ‘‘My father’s dying now, dark bird, you know’’ are moving, even haunting works.

The pick of them all are Anthony Lawrence’s The Language of Bleak Averages (‘‘ … I remembered stories of light- / bulbs dimming, of wind bending glass when people died. / The light held on. The window glass moved / with a copy of my face when I looked at it’’) and Philip Salom’s father dying with dementia, remembering the war (‘‘… ’of Syria, men now dead / walking through the sunlight like an extra line of heartbeats’’).

For all these poets it’s as if their father’s death has brought an urgency to their work, a potent realisation that their world has been irrevocably transformed. Why not mums? Perhaps it’s because fathers are more unknowable than mothers, their relationships with their children more complex, so that their deaths become a puzzle of conflicting emotions to solve.

This anthology seems at war with itself. It sets out to prove that the past quarter of a century has resulted in a rich period of poetry, but the thesis has been undermined by the inclusion of much dross. A more ruthless editor could have given more weight to the editors’ hypothesis by pruning the number of poets to about 40.

Overall this is a comprehensive survey, but it is a safe and inoffensive selection and, as such, is probably a true reflection of the state of contemporary Australian poetry.

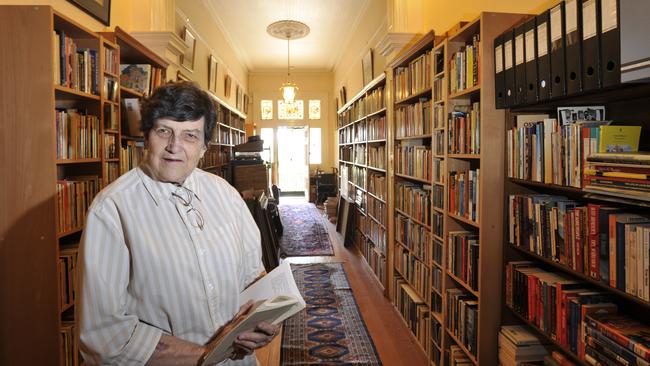

Louis Nowra is a novelist, playwright and poet. His new book, Woolloomooloo: A Biography, has just been published.

***

POETIC INSIGHT INTO OUR INTERIOR LIVES

Martin Langford, one of the editors of the anthology, believes the quality of Australian poetry is at an all-time high — but we need to take notice.

Australia has not always given a receptive ear to poetry, with the exception perhaps of the ballad writers, who it was felt at the time did say things Australians wanted to hear, in a way we wanted to hear them. In our earlier history, this indifference was understandable: for the pioneers, the task was survival. Art and science were luxuries that could come later.

Besides, it takes time to develop a tradition. Poetry, for some reason, is one of the slower arts to become established.

The US had been settled for hundreds of years before its poetry got off the ground. A young country, anxious about its self-esteem, measures itself against more established lands with suits that will be competitive: sport, agriculture, military prowess.

If, as in our case, the parent happens to have a rich literary tradition, then the ex-colony is likely to set that hand aside when it comes to constructing its identity. At least, that is, until it is in a better position to claim it as an asset.

The parent can reinforce this, with the disingenuous part it plays in maintaining the status quo. As long as its editors compile the anthologies and its critics award the praise, then the relative positions of the two cultures will be an unacknowledged element in their judgments.

This is essentially the situation that has pertained so far.

Eventually, however, as a society matures, it will have to consider its relationship with its more thoughtful attainments as well. It doesn’t have much choice about this: they are essential components of a culture.

Any culture that actually produces anything has to be restless and unpredictable — and strong enough to be permanently wary about its conclusions. We accept this in science or in history. Over the past century or so, it has become a key aspect of poetry as well.

The exploratory element in poetry — as in all literature — has always been there, but its more typical functions, in say 1900, were either to tell a story, or to feed our prejudices in a way we found pleasing because of its rhymes, or its vehemence, or perhaps the clumsy but triumphant joke at the end.

Newspapers of the time might print half-a-dozen poems in every issue, but only a minuscule number would still be of interest. Many of the functions of such poems have been usurped by other media. We have talkback radio for our prejudices, and — though poets do experiment with narrative from time to time — novels and movies and podcasts for our stories.

One thing poetry still does uniquely well, however, is to explore our understandings: to ask the questions that are left hanging when the story ends. If science tries to understand the world in terms that are as ‘‘objective’’ as possible — cross-referenced against experiment and other established findings — then poetry increasingly applies those findings to our lives by giving them their emotional weight.

These responses may be shaped by our imaginative lives, but evidence-based conclusions are ubiquitous in contemporary verse. To take a few examples from the anthology: how the ‘‘atomic’’ view of the world invests David Brooks’s Dust; how a psychologist’s finding about the formation of mental images informs Bronwyn Lea’s thinking about the conceptualisation of love in Driving into Distances; how Maria Takolander’s meditation on the movements of her unborn baby (in Foetal Movement) is inconceivable without modern technology.

Australian poets are very good at exploring our shifting understandings, and at registering their impact on our interior lives. They are as good, at least, as our prose writers. Having recently had to read pretty much everything we have produced over the past 25 years, I and my co-editors came to the conclusion there were perhaps 30 poets writing with a seriously high level of skill and insight: with both distinctive and individual perspectives, and the craftsmanship to realise them. We have never had so many poets writing at this level before. If this is a story the media has missed, it is not alone. The universities have not got hold of it either. It is a big story, and will play out over the coming decades.

The point here, however, is that the poets have been fulfilling the role we would expect them to in a creative culture. They are one of its cutting edges — the edge that weighs its understandings verbally.

Now it is the society’s turn. Somehow, we remain trapped in a view of poetry that is more suited to a pioneering age — to an age of unforgiving necessities. In some ways, that is easier: we never like to be disrupted into the present. But we can’t seriously lay claim to being a mature and creative culture unless we are prepared to engage with the understandings that the most thoughtful minds in that culture produce.

In many areas, we are enthusiastic about the new. With poetry, however, our responses seem frozen: an inappropriate reflex left over from some earlier cultural need. Creative cultures explore all the possibilities — even their blind spots.

It is time Australia stopped repeating itself and looked around — particularly when the work is already there.

Contemporary Australian Poetry

Edited by Martin Langford, Judith Beveridge, Judy Johnson and David Musgrave

Puncher & Wattman, 690pp, $49.95 (HB)