Surfing with Tognetti: only a violinist knows the feeling

Review paddles out with Richard Tognetti at the musician’s old stomping ground — the surf off Wollongong — to reflect on 30 years at the Australian Chamber Orchestra.

Richard Tognetti has one hand on his hip and the other shielding his eyes from the bright morning sun as we stand on a hill overlooking a string of surfers taking turns catching two-foot waves.

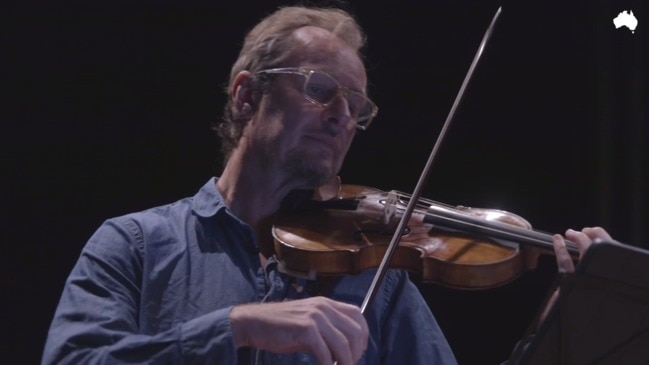

Tognetti, 54, is better known as the artistic director and lead violin of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, but on this hot spring day he has agreed to show me his other passion, surfing, which is why we have come to East Corrimal, a surf beach not far from where he grew up in Wollongong, south of Sydney. The ACO is also performing that night at the Wollongong Town Hall, where Tognetti attended his first concerts as a six-year-old.

“There might be a wave down there,” Tognetti says, nodding down the beach, pondering for a moment before making up his mind. “I’m taking Old Fatty.” The next moment I am trailing behind him, as he sprints down a sand path through the bush to the beach with his curiously named surfboard, under his arm. “That’s the rules,” he shouts. “You always have to run to the surf!”

I might not be so out of breath had we not already surfed that morning for 1½ hours at Sandon Point, a rocky point break up the road, before Tognetti decided we should take our chances on the wind and drive in search of bigger waves. I shouldn’t be surprised: people are always trying to keep up with Richard Tognetti.

■ ■ ■

“Everyone bangs on about the relationship in my life between surfing and music,” Tognetti says with a wry smile. “For me, it is about the posture. Of course the way the sea swells and recedes is like a musical phrase. But some people don’t feel it like that. They don’t feel the music in the sea. Or they don’t feel the sea in the music.”

Our conversation recalls the smug slogan on 1990s Billabong T-shirts, “only a surfer knows the feeling”; any surfer will tell you the joy of catching a wave is hard to articulate because little can compare to the act itself. But that hasn’t stopped Tognetti from giving it a shot. In 2008 there was Musica Surfica, his documentary that explored the connections between classical music and finless surfing, shot on King Island with friend and fellow surfer Derek Hynd and cinematographer Jon Frank, which spawned a concert tour up the east coast of Australia. Then there was 2009’s The Glide, a multimedia concert featuring Frank’s surf footage from around the world with live music from the ACO. Tognetti and Frank continued the collaboration in 2012 with The Reef, another multimedia performance that combined astonishing surf and ocean cinematography filmed around Gnaraloo Station and Ningaloo Reef in WA with music by the likes of Bach, Rameau and grunge band Alice in Chains.

‘Of course the way the sea swells and recedes is like a musical phrase. But some people don’t feel it like that’

Salt is as integral to his being as steel is to Wollongong, and is one of the reasons Australia has been able to hold on to one of its most talented violinists. For years people in the music community have wondered at how long his tenure will endure. Yet here he is, celebrating 30 years at the helm of the ACO.

Tognetti will open his 2020 season with Beethoven’s first three symphonies, a program that will see the 17-piece ensemble swell to more than 50 players to celebrate the composer’s 250th anniversary.

Other highlights include the Australian premiere of The Four Seasons and Beyond, a new take on Vivaldi’s most renowned work by British electronica composer Anna Meredith, Australian heldentenor Stuart Skelton in Mahler’s Song of the Earth symphony and a new electric violin concerto written for Tognetti by Samuel Adams, son of renowned American composer John Adams. In October, the ACO will return to Tokyo to perform at Kioi Hall and to London for its third and final residency at the Barbican Centre. And a tradition will continue when Tognetti leads two of three performances in Wollongong, washing off the salt from Old Fatty and pulling out his his 1743 Guarneri del Gesu violin.

■ ■ ■

We have been in the ocean at East Corrimal for less than five minutes when Tognetti springs to his feet and glides along the face of the wave, moving with its sensuous rhythm. The way the musician surfs is stylish and effortless and at the performance that night I can’t help but notice a similar agility in the way he plays his violin.

The ocean inhales and a line rolls towards us. Tognetti tells me to paddle; he’s paddling too. I think: he’ll take the left-hand side of the wave and I’ll take the right. I point my board back towards Sandon Point and take deep paddles forward. The wave picks me up and I make a bottom turn, only to sense another figure behind me. Oops. I just dropped in on Tognetti. I wonder what he thinks about my accidental failure to observe surf etiquette; the person on the inside has right of way. But the violinist is grinning as he paddles back out then sits on his board and drinks in the sunshine.

“I learned to surf all around here,” he says, gesturing at the coastline, the Wollongong city skyline visible behind him. “There is something about the natural beauty that we all bang on about. It’s where the escarpment meets the sea. And that’s what makes it dramatic. And that’s what makes it dark, in a good way, too.

“That’s why [artist] Paul Ryan’s paintings resonate,” he says, referring to his friend who lives in nearby suburb Thirroul. “They just built the steelworks bang in the middle of one of the most beautiful coastal areas in the world.

“And so it had this great tough working-class environment that is very much a part of my spirit. You can take the boy out of Wollongong but you can’t take Wollongong out of the boy. That’s why I think it is important to come back (to perform) here.”

■ ■ ■

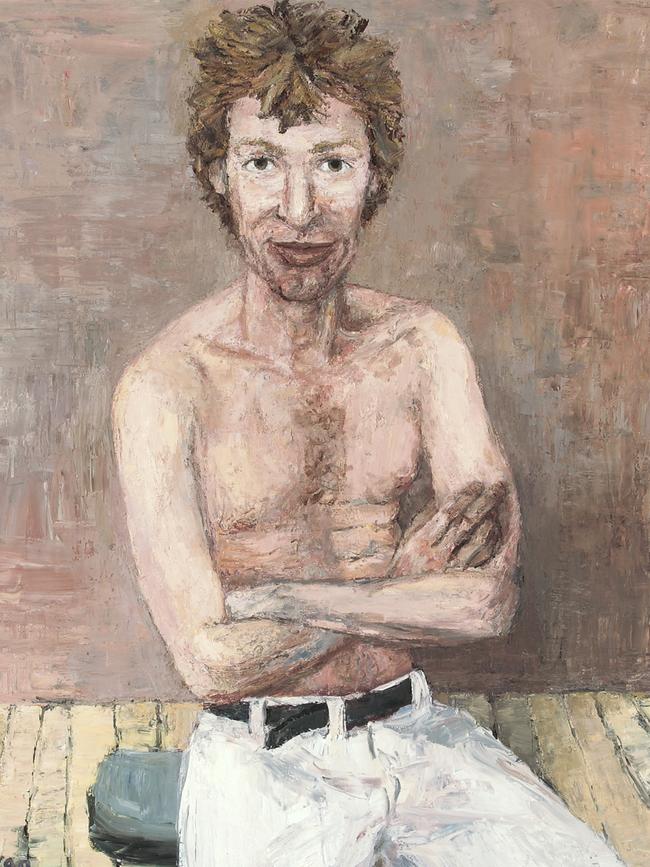

The next day is hotter. Dark clouds furrow over the escarpment and a sprinkle of rain kneads the smell of petrichor from the earth. I make my way up a driveway to a studio tucked behind a house in Thirroul. Two surfboards are propped on the deck and inside there is a freshly painted canvas; a swirl of pine trees, sand and ocean in thick brushstrokes. I immediately recognise it as my favourite surf spot on this strip of coast, Sharkies Beach. This is where Ryan painted Richard, Arms Folded, a finalist in the 2002 Archibald Prize, featuring a shirtless Tognetti sitting on an old barber’s chair.

Ryan met Richard’s older brother, Simon, when they started at the same school aged 15. They lived in walking distance of each other and quickly bonded over art and surfing, paddling out at local breaks including Sandon Point, which in the 1970s and 80s was legendary for its fierce localism.

“There’s stories of Point boys pushing people’s cars over the cliff,” says Ryan, pulling up a chair next to a table buried in empty tubes of oil paint. “Letting tyres down and pissing on people’s towels and stuff was commonplace. Threatening people with violence and actually punching them up. It was really hardcore.”

After surfing, the boys would sometimes go back to the Tognetti house. “It was architecturally designed and there was art, sculpture and ceramics everywhere, and classical music playing. Their mum was an incredible cook and I was like, ‘what is this world?’.”

Irene Tognetti was working as a caterer at the time and father Keith was a mathematician and academic. Richard started learning violin aged six and took group classes in the Suzuki method, which was introduced to Australia by violinists Harold and Nada Brissenden, who also lived in the area. At 11 he attended the Conservatorium High School in Sydney but returned home again when he was 16 to attend Year 10 at Wollongong High School.

“You could hear this violin coming from a room,” says Ryan. “I actually didn’t see him much in those days because he was always in his room practising.”

■ ■ ■

Tognetti is sitting in a dressing room at Wollongong Town Hall as the orchestra warms up on stage. This is the venue he helped save from demolition when in 2008 he gave a free lunchtime performance at a council rally to demonstrate the acoustic value.

“Wollongong has changed,” he says. “I used to care much more about Wollongong than Wollongong cared about me.

“But they’re all my memories. No matter where you grow up, this is where you get your memories for the rest of your life. They’re the memories you’ll have on your deathbed. When I went to Europe to study I had memories of Wollongong growing up.”

Wollongong was a tough place for an aspiring professional musician in the 80s. “It was the f..king peer-group pressure,” Tognetti says, raising his voice over the sublime sounds of the ACO rehearsing. “Here I am with a violin, but there were other kids who stopped playing and they might have kept playing. They might have learned languages, they might have learned the language of music, they might have had more open vistas but they were too embarrassed to walk down the street with a violin.

“I didn’t let it touch the sides and just couldn’t wait to hitchhike out of here — which I did.”

Tognetti says he had “good parents in that they gave us opportunity and exposed us to all sorts of interesting things, the grand life outside Wollongong”. But he hated going to Wollongong High. When he was 16, he told his parents he was going in his room to practise then hit play on a cassette recording he had made of himself and jumped out the window. Some guys “listening to Bob Dylan and smoking weed” picked him up in what he says was “probably an old Holden or something”, not letting memory get in the way of a good story. “It was sort of symbolic. I went to Newtown, Erskineville [in Sydney’s inner west] and felt free.”

He went on to study at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. Then it was Berne in Switzerland to study with renowned teacher Igor Ozim.

Coming from a town that gave aspiring musicians little encouragement tinted his view of the world; if a Wollongong boy can crack Sydney, then an Australian chamber music ensemble can make it in Europe.

“Classical music from Australia, we’ve had incredible racism. I don’t know what you call it, cultural imperialism from people in the UK. That’s not happening these days as they go through their big existential crisis with Brexit.”

When the ACO performed at the Barbican last year, a reviewer for The Times wrote: “Nothing about this orchestra, however, is ever routine … And Richard Tognetti, leading from the front in every sense, embodies everything that makes his band special.”

Its US tour was also positively received: “It’s not easy getting a bead on the particular strengths of the Australian Chamber Orchestra. That’s because this terrific string ensemble seems to shine at anything it undertakes,” said the San Francisco Chronicle.

Tognetti says the standard of playing of classical musicians from Australia today, particularly those coming from ANAM, has given the sector an earned confidence — “I don’t mean an empty nationalistic right, that’s quite different”. For the ACO, this confidence arrived in about 1999 after a period in the mid-90s of having to “fight like hell” for recognition when there was less political appreciation for the broader cultural ecology.

“(Paul) Keating engendered a great argument about cultural significance through Creative Nation but unfortunately the specificity of his own passions drove that argument and drew with it condemnation and he, and therefore we, became an easy target,” Tognetti says of the then prime minister. “Instead of talking about the ecology of the cultural fabric of the country it became about certain individuals and certain repertoire that were his tastes.”

Could it be that the ACO was before its time? Tognetti nods. “We were a hybrid group. We were playing on gut strings, we were playing early music one concert and the next concert playing on modern instruments. We were playing electro-acoustic instruments, we were collaborating with rock ’n’ rollers and Neil Finn and electronic artists in an artistic way, not in a gratuitous way.”

Today, audiences trust the ACO, they know the ensemble can be “quirky”, he says, while maintaining the highest level of playing.

‘I want to be part of the cultural fabric of Australia ... I want to shout and argue for it’

Yet the realisation of any project in an artistic organisation often requires the moving parts on the inside to also come together. He says people wanted to get rid of him when he first decided to combine music with surfing.

“People thought I was nuts with our big multimedia projects because we weren’t playing Star Wars, we were making the films ourselves. [They said] ‘the ACO are making a surf film?’ I had a screaming argument,” he corrects himself, “Or, the other person was screaming at me. Not in the ensemble, but in the management because they had to raise money. [They said] ‘No, I’m refusing to do it’. I said: ‘I’m telling you, you have to do it’. So we made Musica Surfica and it inspired The Reef, which in turn inspired [another project called] Mountain.”

Before he goes on stage to join the orchestra in rehearsal, I can’t help but ask, after 30 years, is there anything that would lure him away from the ACO?

“I can’t think of anything better to do,” he says. “And here’s the thing: surfing really is an integral part of my life. I want to do more surfing. So where would I go? The only place in Europe is south of France but it’s only good September to October, then it gets cold and windy, and I’d hate to be there in summer.

“And I want to be part of the cultural fabric of Australia. I want to push and I want to scream and I want to shout and argue for it.”

The Australian Chamber Orchestra opens its Beethoven 1,2,3 program at Canberra’s Llewellyn Hall on February 8. then tours to Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout