Colm Toibin brings up the bodies in Greek mythology

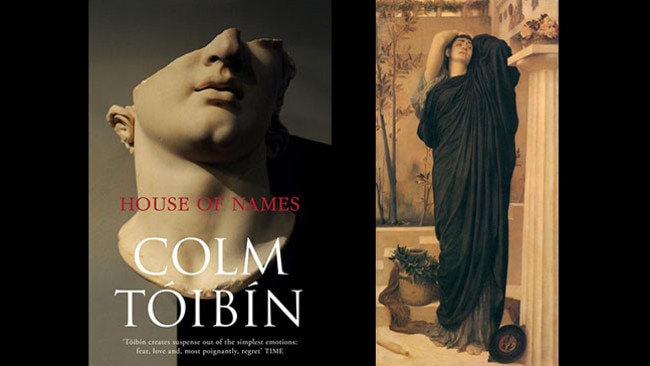

Colm Toibin’s new novel delves into the most infamous dynasty in Greek mythology.

Offsetting the many valiant exploits and fantastical adventures in Homer’s Odyssey are scattered accounts of the mad acts and foul deeds of the House of Atreus, the most infamous dynasty in Greek mythology.

Odysseus refers to one notorious family member when — in Robert Fagles’s evergreen translation — he tells his genial host King Alcinous that his own misfortunes are nothing compared with “the griefs of my comrades”, men who survived the Trojan War “only to die in blood at journey’s end — thanks to a vicious woman’s will”.

That vicious woman is given a name as the ghost of Agamemnon appears and recounts how he and his spoil of war, Cassandra, were murdered by his “accursed” wife: “My treacherous queen, Clytemnestra”.

Colm Toibin’s latest novel begins with a section called Clytemnestra comprising the character’s viewpoint as she makes the steady transition from mourning mother to murderous spouse. We assume Toibin has written another work of fiction that offers an acute psychological study of a famed figure, following on from his 2004 novel, The Master, about Henry James, or his 2012 novella, The Testament of Mary, about the mother of Jesus.

However, House of Names has more than one resident, and contains many angles, various levels and diverse prospects. Toibin gives us Clytemnestra’s testimony, then moves on to bring in the individual trials and sufferings, manoeuvres and machinations of Orestes and Electra, her vengeful offspring. Each portrait proves mesmerising, but the full-length picture is a taut, terrifying and magnificently bold depiction of betrayal, allegiance and misused power.

“I have been acquainted with the smell of death,” runs the novel’s memorable opening line. “The sickly, sugary smell that wafts in the wind towards the rooms in this palace.” Bodies pile up throughout the book, with one atrocity begetting another — “death is ravenous for more death” — and the palace becoming polluted by that smell.

But the book begins with the queasy build-up to the one death that unleashed all others and convulsed and dissolved a family. Clytemnestra relates how Agamemnon duped her into thinking he had arranged the wedding of their eldest daughter, Iphigenia. Slowly the truth dawns on her: Iphigenia was not to have Achilles as her husband, “she was rather to have her throat bloodied by a sharp, thin knife in the open air as many spectators, including her own father, gaped at her, and figures appointed for this purpose chanted supplications to the gods”.

Iphigenia’s death transforms Clytemnestra. From this moment on she ignores gods and oracles, and determines her own fate. She makes palace prisoner Aegisthus her paramour and, most important, she vows to kill her husband — no brave warrior but “a weasel among men”. She plots an elaborate murder and when she finally pounces, knife in hand, the result is, quite literally, a bloodbath.

If Toibin’s opening section takes the form of foreshadowing — a kind of chronicle of a death foretold — then his next part unfolds as a fraught journey into uncharted territory. A “kidnapped” and exiled Orestes breaks free of his prison camp and heads for home across the desolate landscape with two other escapees. Along the way, and through the years, they battle thirst, hunger, vicious dogs, circling vultures and men sent to recapture them.

In time, Toibin rotates his viewpoints again and centres on Electra. We follow her flitting between Agamemnon’s grave and her room, “an outpost of the underworld”, where she observes the ghosts of her father and sister.

Electra considers her mother a woman “filled with a scheming hunger for murder”; Aegisthus is a man “filled with strategies”. When Orestes returns she develops a hunger for murder and a strategy of her own. “You are the only one who can do it,” she tells her brother, working on him until he has an oedipal complex with a difference. The siblings watch their mother, choose a weapon, then put their plan into action.

House of Names is not the first novelistic treatment of Greek myth by a major author this year: David Vann’s Bright Air Black is an equally powerful retelling of the story of Medea. But unlike Vann, Toibin allows himself considerably more creative licence. His tale draws on the fundamental episodes and issues of the main source material (specifically the first two plays of Aeschylus’s Oresteia), in and around which he makes all manner of alterations and embellishments, such as padded-out backstory or extended scenes, fleshed-out protagonists or newly minted secondary characters.

Toibin’s version — more a subtle restyling than a drastic retooling — gives added depth and alternative perspective. We certainly don’t fault his dramatis personae. In Sophocles’s Electra, we get an extra, redundant sister; in Euripides’s Electra, the catastrophic impact is lessened, not increased, when both Electra and Orestes wield the matricidal sword.

In contrast, Toibin’s cast is well-formed and fully functional, with each member an independent force in thrall to their own impulses. Iphigenia arouses pity, Aegisthus instils fear and loathing, Electra is adept at coaxing and Orestes is primed to kill. Toibin’s Clytemnestra is capable of all this and more, and sears each page with her presence.

It is a pity, then, that Toibin doesn’t opt for a fade-out after Clytemnestra’s death. His last section feels tacked on, a weak comedown after a climactic and cathartic killing. When Orestes complains about being trapped in “a pale aftermath”, we sympathise with him. Had Toibin stuck closer to Aeschylus there would have been additional drama in the form of Orestes being driven mad by his mother’s Furies.

Yet what Toibin gives us for the bulk of his book — from that initial scent of death to death itself as a final reckoning — is nothing less than a tour de force. House of Names takes the reader back in time and into both a house of horrors and a “house of whispers”, a place filled with brazen cruelty but also furtive conspiracies to settle scores. It is a brutal read, but like ancient audiences before us we are expertly led from savagery to civilisation, and emerge from dense darkness into brilliant light.

Malcolm Forbes is an Edinburgh-based critic.

House of Names

By Colm Toibin

Picador, 272pp, $29.99 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout