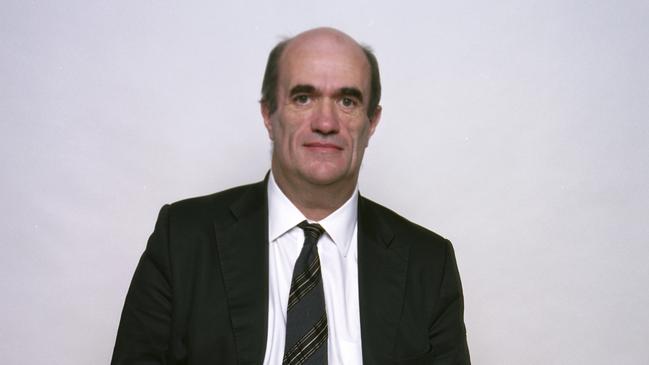

Colm Tóibín’s Long Island: a dazzling sequel to Brooklyn

What to do when an angry Irishman turns up on your doorstep, insisting that your husband has impregnated his wife?

It’s a long time now since Colm Tóibín riveted the world’s attention with The Heather Blazing – a novel about the earlier phase of the Irish troubles, executed in a style of high classical realism. Tóibín has written with a moody variegation ever since. A decade and a half ago he produced Brooklyn, which looked like the first book in an Irish-American saga with its heroine Eilis, and the Italians she falls in with, in the battered borough of New York.

Now we have its successor, Long Island – some kind of step up socially, perhaps – and it has a dazzling verbal authority as well as a vertiginous plot which allows for wild melodrama, wacko narrative loops and turns, and an extraordinary latitude on the characters’ parts to procrastinate about the heart, and to imagine what their potential lovers might be imagining.

In one way it’s a very Celtic shaggy dog story but Tóibín also has mesmerising narrative powers which allow him to tell any given story every which way.

The opening presents our heroine confronting an angry Irishman who tells her that her husband has got his wife pregnant and that when the baby is born he will not tolerate it but will dump the newborn on the doorstop. The one thing she is sure of is that she will not abide having her husband’s infant in her house or under her care.

This last proposition is relevant because the Italians – her in-laws – think that one way or another they have to bring up the offspring rather than have it put into an orphanage.

All of this mafia-like drawing up of bridges is done with a massive satirical brio, as the in-laws swear fealty to each other and insist that what they have said to each other (in gross defiance of their sister-in-law) must under no circumstances be repeated. There’s even a gay lawyer brother, who’s made it to Manhattan, who not only pays the college fees (at Fordham) of Eilis’ daughter – endearingly named Rosella after her bestie Rose – but who also plays a Cyrano-like role writing everybody’s letters in proper English.

The Italian-American scheming is done with an exuberance and wildness that is at the edge of absurdism but Toibin’s sense of human emotion is consistently speculative and shrouded in doubt. When Eilis sees she could never win, she heads for Ireland, uncertain of whether she’ll stay with her nerve-racked husband who is terrified that she won’t come back. Not only is she heading for the rural Ireland of her childhood she is also going to be joined in a matter of weeks by her adolescent children – the bright as a button girl and her facetious younger brother.

She is also forced to confront the man who fell in love with her 20 years earlier (on her last visit) not realising she had a husband in America. There is also an old friend who runs an especially horrible sounding fish and chips shop whose patrons try to beat down the doors and throw up everywhere. Life is not made easier for anyone by the fact that the man who once loved her has agreed to marry the chippy woman but has to keep this secret, even as he falls all over again for the now middle-aged colleen from Long Island.

For great tracts of time you gape at the kind of narrative licence Tóibín allows himself. He deliberately indulges a semi-farcical level of improbability but then invests it with a vast armoury of introspection and reverie where the characters are constantly saying things and not saying them because of the reactions they anticipate or fear.

You can say this works like a nervous tick if you like but that is to underestimate Tóibín’s massive dramatic powers. He brings his characters alive even when they’re acting preposterously (in fact, especially then) and this has a vivacity that captures at a level of comedy and psychosexual frailty just how mad more or less credible human beings can be.

The hotel owner who has to choose between women without having much of a will of his own is beautifully observed and we’re full of sympathy for his taciturn self-possession even when he’s being a hopeless git.

This is a novelist who loves the comedy of competence and the craziness of what follows when lunatic propositions are carried to their logical conclusion by very recognisable people who don’t in practice know their arses from a hole in the ground.

Tóibín has the great power of conjuring visualisation and it’s hard not to be swept away by characters you can see – effortlessly – even when they’re behaving madly. He’s also very good at digression: there’s a beautifully done account of a woman – the chippy – buying clothes for her daughter’s wedding while also being persuaded by a canny saleswoman of the outfit she will need later for her own projected wedding in Rome.

You may find yourself with Long Island taking in the first two thirds of the book lingeringly, only to discover at the 200-page mark that you’re going to finish it rapidly. It’s also worth remarking that the ending is a cliffhanger and we don’t get (as we think we might) some resolution to the unwanted baby or the chorus of Italian manipulators. But this is probably good news for Tóibín’s fans because it suggests that the successor to Long Island is underway.

Colm Tóibín is a writer with the highest level of gift, whatever you make of his achievement.

As it happens this makes him a master entertainer who can make the novel into his chosen circus. A fair fraction of readers are going to be kept up past the dawn by this one.

Peter Craven is a culture critic

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout