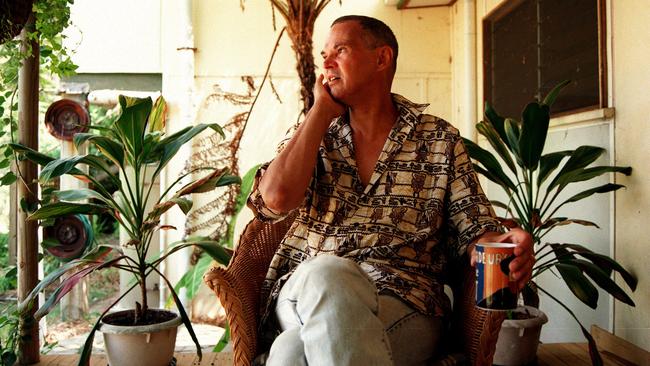

Colin Johnson aka Mudrooroo: the outcast

As a writer, Colin Johnson aka Mudrooroo deserves our respect.

Our first pandemics were the deadliest. When Europeans arrived in 1788, the Aboriginal population of the Australian continent was estimated at more than 300,000. Within three years, smallpox had struck. Peoples who had never before been exposed to European diseases soon had their numbers decimated by the ‘‘pox’’, followed by influenza, measles and tuberculosis.

We tend to concentrate on ‘‘guns and steel’’ when discussing the tragic and destructive encounter of white and black worlds in Australia. Human agency can be inferred from instances of frontier violence, after all: contemporaneous intentions may be clarified, blame apportioned. Yet the cataclysm experienced by pre-contact indigenous Australian society came from germs as much as any other source.

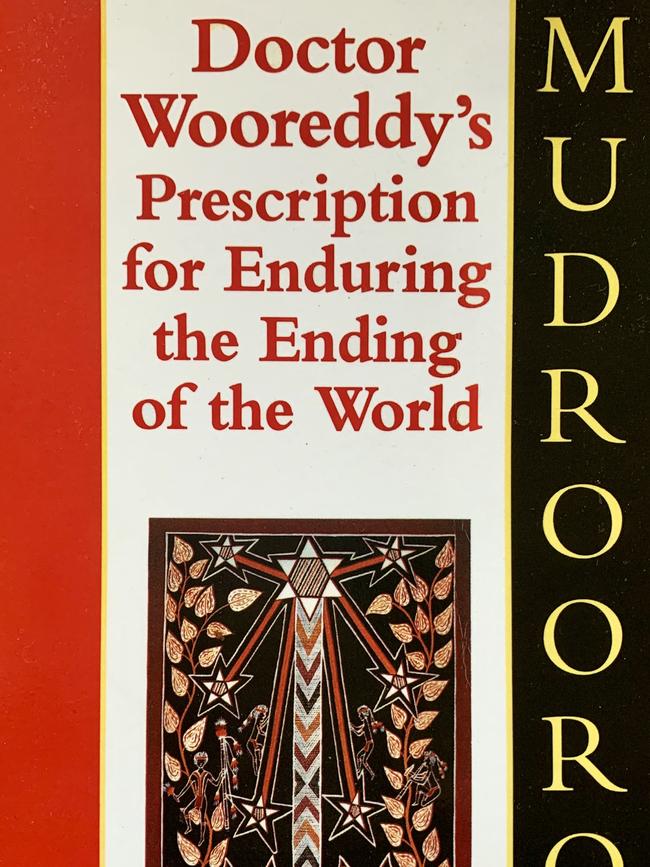

In his 1983 novel, Doctor Wooreddy’s Prescription for Enduring the Ending of the World, recently reissued by tiny publishing outfit ETT Imprint, Mudrooroo (the name Colin Johnson adopted in the early 80s) calls it ‘‘the coughing sickness’’.

Whatever specific disease he refers to, it makes its way through Tasmania’s Aboriginal population like a swung scythe. Indeed, Mudrooroo’s novel, with its clinical title and fatalistic tone, turns out to be the journal of a plague: a pestilence visited on mortals by a higher power.

Its indigenous characters decline to ascribe the unfolding disaster to those white invaders who landed in Van Diemen’s Land in 1804. Described as ‘‘ghosts’’ or ‘‘num’’ in its pages, these people are regarded by the locals as neither smart nor organised enough to be fully responsible for their actions. They are merely vectors for the transmission of otherworldly forces: a symptom of some spiritual malady.

This approach results in a startlingly different retelling of the story of Tasmania’s ‘‘last’’ Aborigines. In Mudrooroo’s hands, they are not childlike innocents but members of a knowledgeable and sophisticated culture who understand white arrival in theological terms.

They know the invaders have disrupted an immemorial order by their presence; their animals and agricultural practices have changed the island’s ecology in damaging ways.

Likewise, the murder and violence that attends their appropriation of land has thinned the ranks of elders who carry the law and maintain social cohesion.

But for Wooreddy, a real historical figure — a boatbuilder and clan chieftain of the Nuenonne of Bruny Island, who spoke five dialects and maintained a proud adherence to local customs and dress during decades of upheaval for his people — knowledge of the end times precedes European arrival.

As a boy, he inadvertently touches a sea creature lying on the island’s shore. He feels it is an evil omen, since the men of his people were forbidden to enter the sea or even to gaze upon fish, which were taboo (the sea was women’s realm; they were permitted to swim and to collect crabs and crustaceans).

That this moment should correspond with the arrival of one of the first ‘‘floating islands’’ of the num — a ship making its way to the future site of Hobart on the Derwent River — merges in his mind with a curse he understands to have been directed by the spirit, Ria Warrawah, a devilish essence that comes from the sea.

‘‘Nothing from this time on could ever be the same,’’ he thinks. ‘‘And why? Because the world was ending!’’

The boy stood in a trance and learnt that he would live on to witness the end. He had been chosen and would endure through the power of his Truth. It was a charm of awful power. He received it as his initiation and then it retreated to live on in a corner of his mind.

Doctor Wooreddy’s Prescription is the account of his life, with some liberal fictional embellishment, as it unfolds in the light of this knowledge. Moodrooroo tells the story in large part from the Nuenonne man’s perspective. He grants Wooreddy intelligence and guile, and also a tragic sense of the life to come.

Wooreddy grows up and marries, only to lose his wife and children to disease. He watches as his people succumb to illness and despair, and notes that the remaining women of the island spend increasing time with white whalers based at Bruny Island’s Adventure Bay.

One of these, Trugernanna (best known to us as Truganini, the most significant indigenous figure to have emerged from Tasmania’s 19th century), catches Wooreddy’s eye. She, too, has lived through awful events, having lost her fiance and sisters to white violence, and having been subjected to rape by white men.

But she is strong and quick-witted; and while she shares Wooreddy’s sense that culture must be maintained, she also appreciates that adaptation is her best chance for survival.

The pair find that opportunity in the figure of George Augustus Robinson, who in reality became the Chief Protector (the title is deployed with savage irony here) of Tasmania’s Aborigines. Moodrooroo has plenty of sport with Robinson, painting him as a risen working-class man, deeply ambitious but with a sincere if misdirected Christian belief, and yet he gives some credence to Robinson’s more decent impulses.

Much of the novel is given over to Wooreddy and Trugernanna’s travels with this man, whom they call ‘‘Fader’’ (the patriarchal moniker pleases him): first to the state’s west coast, where they guide him in search of remnant tribes — who he hopes to gather and take to some site where they will be free of settler violence and inculcated with his imported faith — and then on to the indigenous settlement on Flinders Island.

Readers know how this story ended: Robinson’s protected isle turned out to be one more pestilential prison, and his efforts only hastened the demise of many of Tasmania’s remaining indigenous peoples. But since we watch this through Wooreddy’s eyes, the impetus is shifted.

Yes, Robinson’s efforts were ultimately disastrous. For those Tasmanian Aborigines who cleaved to his plan, however, the project was the best option available. Mudrooroo shows Trugernanna and Wooreddy as active agents during this period: chivvying the white man, smoothing his passage among the tribes of the northwest, arguing on his behalf.

That recasting of agency feels oddly modern.

It has the effect of placing indigenous voices and indigenous views at the centre of an experience that, too often, has been written from white perspectives.

Doctor Wooreddy’s Prescription looks forward, to the more complex and expansive fictions of Kim Scott and Alexis Wright, and is told in a Latinate prose whose dispassionate poise generates more emotion than readers might expect — the mounting sadness it narrates paradoxically increased by the author’s formal remove.

The mystery of this novel’s long absence from discussions of indigenous literature in Australia can only be explained by recourse to Colin Johnson’s larger effacement.

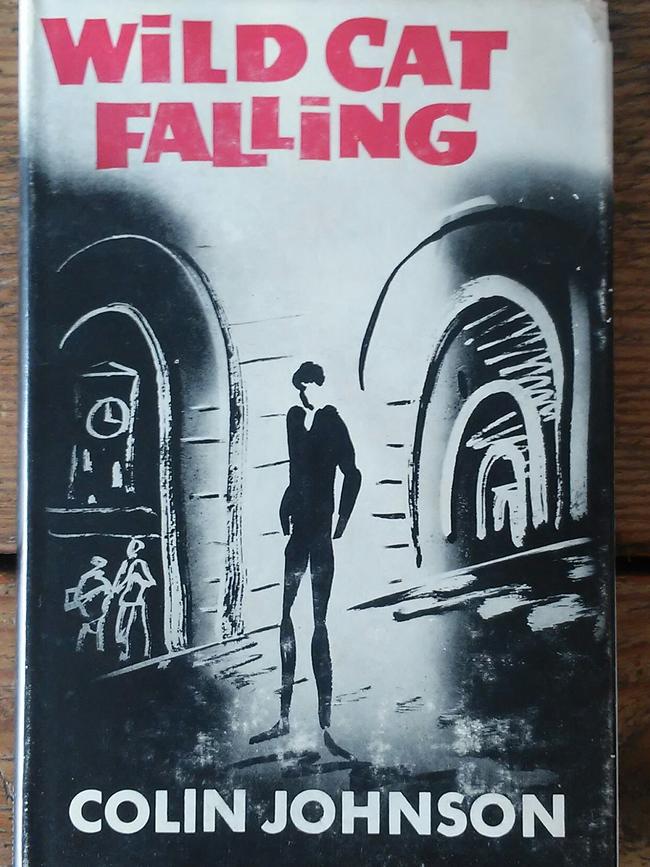

Here was the man who, in his 20s, wrote what is regarded as the first indigenous Australian novel (the Kerouac-esqe Wild Cat Falling from 1965), and who went on to establish a series of indigenous studies departments at Australian universities.

And yet. The author and scholar who published the first full-length study of indigenous literature in this country (Writing from the Fringe in 1990) is not to be found in the pages of the PEN Macquarie Anthology of Indigenous Literature.

His novels, plays, poetry and nonfiction languish out of print, or else are overlooked when published by modest outfits such as ETT. Many will recall that, in 1996, Colin Johnson’s sister, who had lived as a white woman for 50 years, claimed that her brother’s claim to indigenous affiliation was fraudulent: at most, he had an African-American forebear. It didn’t help that Johnson had recently accused Sally Morgan of a similar imposture for her hugely successful memoir, My Place.

Whether it hit a literary community still smarting from the Helen Demidenko affair, or an indigenous community growing more determined to protect its stories from further whitefella annexation, Johnson’s career was finished, his achievement annulled.

He went to India and Nepal for a number of years, only returning to Australia for the final decade of his life.

When he died in January 2019, only a scattering of notices recorded his passing.

Doctor Wooreddy’s Prescription makes such willed forgetting painful. It is a fine, lucid novel, elegiac in spirit, bleakly humorous, tough-minded yet tender towards its subjects. It should fairly be viewed as a significant event in both black and white literature in Australia.

There is an understandable sense that those who muscle in on indigenous communities without true kinship are just one more instance of colonial appropriation, to be resisted and called out.

But the life of Mudrooroo complicates matters. Ten of his siblings were taken by West Australian government authorities when his father died, shortly before his own birth, in 1938. Aged nine, Johnson himself was institutionalised, sent to the notorious Clontarf Boys Home. Years of petty crime and prison followed.

When, afterwards, he joined a release program to put his life back on the rails, it was one designed for indigenous youth.

His life mirrored in all the worst respects that faced by indigenous Australians during the latter decades of the past century. Yet he devoted his career to writing, studying and celebrating indigenous literature — a field that he, among others, helped to bring into existence.

It is not for me to argue Johnson/Mudrooroo’s claims to indigeneity; that judgment rightly belongs to those with the cultural background to adjudicate. What can be said, though, is that the author’s life, in its tribulations and triumphs, comported with Aboriginal experience. He lived in energetic sympathy with those who had suffered, survived, and sought to overcome their situation. For this, at least, he deserves our attention and respect.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

Doctor Wooreddy’s Prescription for Enduring the End of the World

By Mudrooroo Narogin. ETT Imprint, 220pp, $29.95

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout