Clive James’s The River in the Sky: epic poem as the force is fading

Clive James’s epic poem shows the power that can be found even when a force is fading.

There was a time when readers regarded Clive James’s poetry in much the same way art lovers regarded Winston Churchill’s oil paintings: as ancillary matter to the main event, amateur recreation earned from professional triumph elsewhere.

The James of my youth and young adulthood governed in prose: first with those firecracker critical essays and television reviews, showering audiences with glowing filaments of insight and appreciation (as he once observed of Randall Jarrell, James is one of those rare figures as interesting in affirmation as critique); then with a trio of candidly self-lacerating memoirs, recalling those pre-fame years when his unfocused ambition and temperamental conceit were dashed against the reef of adult experience.

The travelogues and novels, broader cultural criticism and coffee table monographs came with such Taylorised efficiency over the following decades, were so full of fluency and dash, and so evidently of a piece with James’s broadcasting persona, that they obscured the degree to which his larger, more enduring ambitions lay increasingly with poetry.

Recent years have put paid to that view. Long gone is the metronomic ribaldry of his early narrative satires, versions in heroic couplets of his TV monologues. Now we have valedictory monuments, funeral songs: the autumnal translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy from 2013; the 600 pages of his Collected Poems, appearing in 2015 and covering more than five decades of verse; the Poetry Notebooks in 2014 and two sundry volumes, including last year’s Injury Time. It is as though James used the sheer weight of paper publication to shift the scales of his reputation. Whatever his motivation, the tonal swing that accompanies it is definitively towards the elegiac.

The River in the Sky is the final expression of this evolution: a 122-page poem written in free verse with varied line lengths that chop sentences into syntactical splinters or expand them with a grave flourish across the page. Those who admire James’s aphoristic verve but dislike the carpentry of his rhymed couplets will find only some sly assonance and half-rhymes here. This is a verse epic that lies closer to James’s vers libre Dante translation than his own more formally conservative poetry.

The lovely title refers to the Japanese term for the Milky Way. It was first chosen more than a decade ago for a multi-volume work of fiction envisaged by James, based on World War II in the Pacific theatre, the conflict that swallowed his prisoner-of-war father and left his mother a widow. That period and the long shadow it cast over his life are present here but treated glancingly, a formative grief marbled through the narrative.

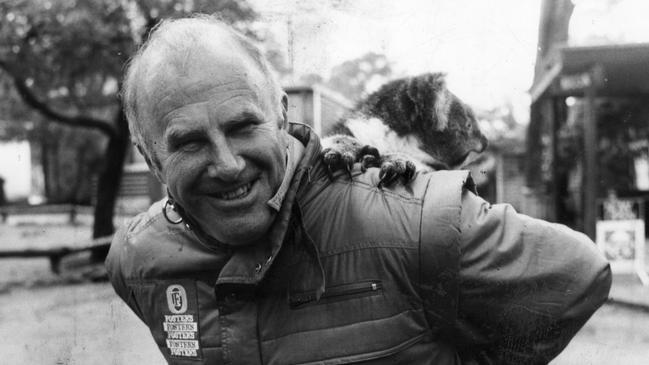

It is old news now that James fell ill and, instead of pursuing the larger project, spent the intervening years battling leukaemia, emphysema and kidney failure: a trinity of maladies that would have killed him far sooner had he not been the beneficiary of an experimental drug treatment. While even James has admitted ruefully that rumours of his demise have been premature, this book has the look and feel of a final testament, dedicated to his wife, Dante scholar Prue Shaw.

As with many wills, James, though reduced in body and mental energy, has used his remaining strength to divvy up his worldly goods. And since he is a writer first and foremost, his wealth is tied up in memories: of people, places, concerts, paintings and books. “Now, one last time,” he begins, “my fragile treasures link / Together in review.”

The poem proceeds in a manner in keeping with its creator’s state of mind: fragile and unstable — “a kitten on a treadmill” — yet still stuffed with stray material.

Restricted to his home in Cambridge and his place of treatment at the nearby Addenbrooke’s Hospital, James finds himself prisoner in a benign cell. He’s wheelchair-bound but retains access to a winnowed library, his family and a storehouse of accumulated knowledge and recollection. What follows is a work of dashcam mortality, its pages a mental screen on which the poet’s memories flow in out of sight, each image linked by association with the next:

All is not lost, despite the quietness

That comes like nightfall now as the last strength

Ebbs from my limbs, and feebleness of breath

Makes even focusing my eyes a task —

As when, before the merciful excision

Of my mist-generating cataracts,

The money spiders dwindled in their webs

Between one iron spandrel and the next

On my flagstone verandah, each frail web

The intermittent image of a disc

That glittered like the Facel Vega’s wheel

Still spinning when Camus gave up his life,

Out past the journey’s edge.

The French existentialist’s fatal car crash segues into an image of the plain white headstone that marks James’s father’s burial place in Hong Kong: utterly distinct individuals, lost thousands of kilometres from one another, yet joined in James’s mind via a third memory.

It all seems random, but is not: the image of death as colour evacuated to pure whiteness that recurs throughout refers to that vision of secular extinction presented by Philip Larkin, a touchstone poet for James across more than 40 years, in his late masterpiece Aubade:

Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can’t escape,

Yet can’t accept. One side will have to go.

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

The sky is white as clay, with no sun.

Work has to be done.

Postmen like doctors go from house to house.

This strategy is a rich one, since through the years James has accumulated an astonishing cache of remembrances to project. But since this particular poem plays out under southern skies, or at least the thought of them, the jewel box clusters of image and memory shift continuously between the Australia of the poet’s childhood and youth, and the northern hemisphere of his maturity.

The Kogarah of James’s beginnings merges seamlessly with the European culture he continues to inhabit, as an idea and a geographic designation. The advantage of this tacking between hemispheres and cultures is that the more baroque memories James summons — being shown original Degas pastels by a Hapsburg princess or chatting with Georg Solti at Buckingham Palace — are halted and undercut by a swift return to thoughts of plane-spotting as a child at Kingsford Smith Airport or the surf at Curl Curl. Australia’s honest vulgarity has a bathetic effect; it pricks the bubble of pomposity that lurks in James’s public fame.

But it also has the effect of ennobling and giving a mythic sheen to the great Australian ordinary:

When I tell Australians now

That I saw Keith Miller play

They realise how old I am:

Like having been there for Troy,

Like having seen

The flare-path for great Hector

Guiding him home.

Fine as lines such as these are, it seems a pity that James feels the need to import a European mythos to achieve his effects. Surely there is so much already present on this continent: history and culture that precedes that of the so-called Old World by tens of thousands of years. That said, James is on the money when he concludes that the rest of us don’t ponder over our past, whether colonial shallows or Dreamtime depths, much either:

For ours is a land of legends

That seldom recognise

Each other’s names.

It isn’t history that we lack

It is the habit

Of thinking in it.

And the most arresting sections of the poem tend to occur when the poet’s mind heads south. It is here that a true ache of longing — for home, for the vividness of those early memories, fixed with greater clarity as though through exposure to a more brilliant light — is felt. James is less performative in recollection this time around, when compared with the memoirs; each reminiscence is now so closely shadowed by the possibility that mortality will negate it.

Still, those passages that deal with one of James’s last trips to Sydney have a phantasmagoric power and simple loveliness that no comic prose riff, no matter how deft, could replicate:

The ferries growled and piped. On foot below

The shedding Jacarandas, gulls patrolled

Like condescending white supremacists

Sharing with pigeons the enhanced green lawn,

The purple passage that announces spring

In Sydney, our October tapestry

Flown in for two weeks from a Loire chateau.

Crossing the harbour to Luna Park, James is confronted by the shades of his early life: the film stars he adored on screen and the primary school teachers who had his measure, his long-suffering mother and his long-lost father — the last whose absence is registered as a grief made crueller by the fact the poet has no recollections to hang his grief upon. (James’s father, Albert, a prisoner of war in Japan since 1942, died when the plane returning him and others to Australia crashed in a typhoon, 10 days after the war’s official end, when Clive was six.):

But he saved the future for me

Though it began in turmoil

And the bitter, aching cries

Of my dear, stricken mother

— Unhappy Queen! Then is the common breath

Of rumour true, in your reported death

And I, alas the cause — So Dryden speaks

For Virgil, and I hear it: my first death,

But some sense of beauty absolute

And undisturbed

Has haunted my life always …

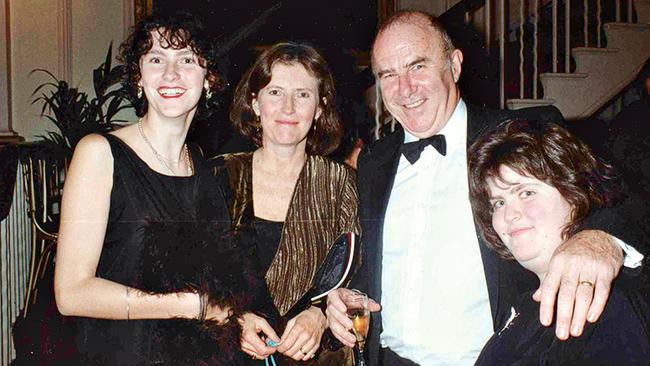

This palpable sense of regret is not restricted to his parents. At points in the poem James turns his attention to his wife, Prue, and in a break from his long-held policy of privacy when it comes to his immediate family, he addresses her directly, both to register his gratitude and, albeit implicitly, his sense of shame over past transgressions. When, halfway through the poem, James writes the line, “And you and our two daughters / Built this paradise for me”, the shock of domestic recognition is bolstered by its delayed appearance. Vladimir Nabokov pulls off a similar trick late in his autobiography, Speak, Memory!, when it suddenly becomes clear that the author’s wife and son have been his presumed audience all along.

What becomes clear is that these technical touches are not extrinsic to the poem’s emotional force; they are central to it. The poet may claim that, “All I can do is make the pictures click / As I go sailing on the stream of thought”, but what James is really doing here is incorporating his frailty into the architecture of the lines. He is placing formal restrictions on himself quite as strict as those in his more obviously prescribed verse to create a form appropriate to his circumstance.

His memory is “lent power / By the force of its fading”. Never one to miss an opportunity to get writing work done, James even jokes that his ashes, placed in an hourglass, would use gravity to give at least the impression that he was still gainfully employed.

It is the harvesting of his own fading as a stylistic effect that matters. It turns what might otherwise have been little more than a YouTube session built from the algorithm of his fancy, into a wrought literary document.

Yet none of this subtle technical effort would count for much — a broken trot after the gallop of the writer in full health — if there weren’t also some wisdom won from the taste of finitude. This is a rare instance in which James mostly resists the opportunity to parade his talents and his ego. The River in the Sky finds the poet shaved of his locks.

The candidness with which James acknowledges this decline, the gentleness with which his mind lights upon memories that are set to be lost forever, creates a sense of melancholy, a sustained sombre mood that, elsewhere in his oeuvre, might be no more than a prelude to one more barnstorming cadenza. It turns out that incandescent intellect is best viewed in chiaroscuro.

Back in 1992, James reviewed a verse epic by American Galway Kinnell. He wrote of The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World that it was a great poem; great because it existed on the ideal axes between having the right things to say and the correct theme to contain those things being said. The vase perfectly held its bloom:

It was the right moment; Kinnell was the right man; and a poem was written which was wonderful against all the odds — even those formidable odds posed by the very business of being a poet at all, in an age when art has become so self-aware that innocence can only be found at the end of a long search.

This, too, was the right moment; James was the right man; and he has indeed written a poem that is “wonderful against the odds”.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

The River in the Sky

By Clive James

Picador, 212pp, $35 (HB)

-

THE RIVER IN THE SKY

I always travelled better

When I was not a guest

And owed no one a favour.

On a flagstone forecourt set into the lawn

That later swept down to the river Plate

From that grand house on the coruscating hill

The first year I went back to Buenos Aires,

The tango dancers gathered in the dusk

And as the night came on, the burning lamps

Killed insects while the dancers brought to life

The spirit of their lovely craft. I, too,

Was blessed that night, the merest interloper

Among the home-grown adepts, but when I

Was told that the most delicately gracious

Of all the dancing ladies was stone blind —

You need to know that she danced like a dream

And I had watched her until my eyes ached —

For once I got my courage out of hock

At the right time, and I asked her to dance

Careful to tell her that I looked like Errol Flynn,

So she need not fear she was ill-matched.

She’d hardly heard of him but still she laughed

And as the opening chords of “Caminito”

Reached out into the night, she reached for me,

And straight away I was in charge of her

As if my task were steering a sweet cloud

Through halls of air. Although, in her high heels

With lacquered straps she was as tall as I

Almost exactly, she made up for that:

She warmed my shoulder with her tilted cheek.

The night was warm already. Now it burned,

As if the way ahead were carved by starlight.

A time to remember, as I breathed her perfume,

That the tango began as a parade at court

Before it was plunged by history

Into the squalor of the dives and docks.

I even dared to steer her through a puente

That laid her out as if embracing sleep

On a couch of night under the silver stars.

If you’re a dancer too you’ll know too well

To make her lean that much is the best chance

To drop the woman even if she can see,

But this one gave me all her confidence:

Gave me her life, in fact. Beyond that night —

Beyond, indeed, the third dance of our tanda —

I saw her never once again, not even

In a fevered dream; but the very fact that she

Had never once seen anything stayed with me,

And is with me now, as now she is with you,

My young male readers, poets of the future

As I sort my books and grammars

!Quién sabe, si supieras

que nunca te he olvidado … !

For the long flight back to England

And waiting for me there

At the far end of the river in the sky

Would be the river caves

For as if my fate were sealed I had begun to dream

Of how my life might end

Only a month before my health broke down,

I sat at Rossini’s on the Quay

Where Sydney is at its most magnetic,

And I wrote of the blind girl in Buenos Aires,

That other mighty dreamland on the water.

The ferries growled and piped. On foot below

The shedding jacarandas, gulls patrolled

Like condescending white supremacists

Sharing with pigeons the enhanced green lawn,

The purple passage that announces spring

In Sydney, our October tapestry

Flown in for two weeks from a Loire chateau.

Sitting to write, as I had often done

For years then, at Rossini’s on the Quay —

The outside tables don’t catch too much sun

Late in the day — I looked across the harbour

To Luna Park where it nestles at the foot

Of the Bridge’s north-west pylon on the lip

Of Lavender Bay, the very name a joke,

For there the reeking prison hulks were anchored

In the colony’s first years. The Park was built

Before my birth. My mother took me there

When the war was not yet over, and I saw

Soldiers dive down the hill-high slippery dips

In the hall called Coney Island — no one knew

The name was a cheap import — heavy-booted

Surfers in uniform on wooden combers

In flight above the bumps, gripping their thin

Slick mats, harbingers of the boogie-board.

Young couples, queuing for the River Caves,

Nuzzled each other’s faces. Why was that?

Vaguely I guessed that the whole adult world

Must feel far different to the people in it,

Even in here, where they behaved like children.

Like children, adults on the Tumblebug

Would sick their Fairy-Floss. A flood of noise

Ran south out of the bay into the city

Except on Sunday evening. Silent then,

The Park drew breath for one more shouting week,

A rhythm it maintained until the winter,

When it shut down. But winter was very short.

In spring it opened up again, as loud

As a painted silk tie from America

With a fat knot. Local residents wore ear-plugs,

Held meetings and wrote letters to the Herald.

Men in white coats took some of them away.

So it roared on until the year I left:

Before the old Big Dipper was torn down

You could hear the shrieks of girls across the dark,

Trapped voices from the blazing jewel-box,

Le Jardin de Plaisir with coloured gravels,

Our Vauxhall Gardens. Everyone went there

At least once in a year while they grew up

Until the Ghost Train burned. From that night on

The place was rigged for safety, shorn of thrills —

Fifteen years later, when I first came back,

The volume had been turned down to a murmur —

And rebuilt often, yet retained its face:

A plaster clown whose big mouth held the turnstiles.

Extracted from The River in the Sky, by Clive James, published by Picador.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout