Clive James’s Latest Readings reflects a blaze of clarity

From Hemingway and Conrad to Patrick O’Brian, Clive James offers an eclectic feast of critical reflections.

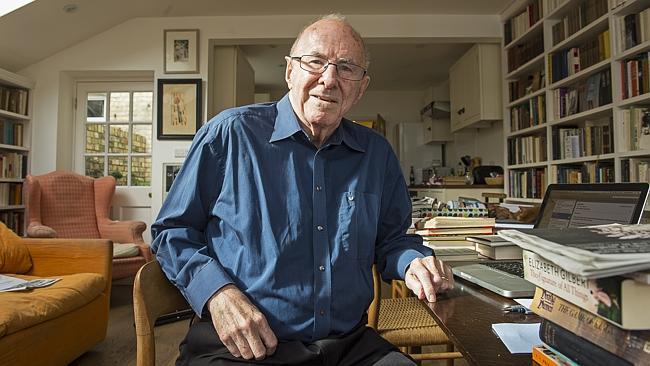

In 1623 John Donne, the great wit of his generation, lay tormented by fever, convinced he was soon to die. When the fever broke, Donne wrote a potent meditation on sickness, death and the love of God, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, from which we draw the adage “never send to know for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee”. Our own great wit, Clive James, is near the end. He has leukaemia. His lungs are tattered from emphysema. He’s down to one good eye. Latest Readings, James’s excellent new book, is a meditation on sickness, death and his love of secular gods, literature and reading.

When first diagnosed, James was despondent. He could “hear the clock ticking” and wondered if “it was worth reading anything both new and substantial”. “I was ready,” he says, “to settle down on my deathbed.” But James recovered his passion: “If you don’t know the exact moment when the lights will go out, you might as well read until they do.”

James reads through his sickness, in spite of and around it. During intravenous antibiotics and “what seem gallons of immunoglobulin”, he reads Joseph Conrad and Stephen Edgar. Told to “ambulate” by his doctors (warding off thrombosis), in summer he walks to Hugh’s bookstall in the Cambridge markets and in winter paces “up and down the kitchen”, with Rudyard Kipling and Samuel Johnson held “in front of [his] nose”.

Half his books were culled in the move from his London base back to Cambridge, but he roams the thousands remaining, “old purchases begging to be read again even as the new purchases came in at the rate of one plastic shopping bag full every week. Insanity, insanity.”

In Latest Readings, James brings us into the book-lined kitchen where he works, volumes overspilling his shelves on to the counter. And he tells us what he’s reading, “mixing books of obvious seriousness with books of seeming triviality; as I always have, in the belief that culture is a matter not of credentials, but only of intensity”. In doing so, he shows what makes him our pre-eminent critic: vast learning, treatment of both high and popular culture, and above all an enthusiasm for literature shared in a prose that is at once earthy, sparkling and erudite.

The book’s content is enjoyably eclectic — “my plan for the organisation of this volume: there isn’t one. It just sort of happened.” James ranges through the heavyweights. “I have spent a good part of my adult life reading books about Ernest Hemingway,” he writes, “and I don’t want to die among a heap of them, but they keep getting into the house.”

He revisits Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, a beautiful swagger of a first novel: “the sharpness of the details I remembered — the chestnut trees of Paris, the running of the bulls in Pamplona — was a sufficient reminder that the book had always struck me as fresh and vivid, the perfect expression of a young writer getting into his stride”. Discussing Paul Hendrickson’s book Hemingway’s Boat, James analyses Hemingway’s complexities, a personality “so extravagant that his creative work occupied only a small corner of it”.

Hemingway portrayed himself as a “man of discipline” and his friend F. Scott Fitzgerald as a feckless “rummy”. But Hemingway was a prodigious booze-hound, and James sees him as a study in waste, his mind ultimately ruined by drink. As James recognises, the younger Clive wasn’t shy of a pint or a smoke. Yet he is a “Puritan” when it comes to self-harmed talent. His own, as the wit and crackle of Latest Readings shows, works just fine.

Hemingway and Fitzgerald were both guests of the legendary patrons Sara and Gerald Murphy, said to be inspirations for Nicole and Dick Diver in Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night. Writing on Amanda Vaill’s Everybody Was So Young, James evokes the languid world of the Murphys’ Antibes house in the 1920s, where American writers mixed with European greats: Pablo Picasso, John Dos Passos, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald, furniture-breaking drunk. “You can see yourself lounging about on the beach and feeling bound to start writing a masterpiece, if not today then tomorrow.” The Murphys’ “little kingdom generated a specific texture of bliss that was remembered by all who touched it”.

Anthony Powell’s 12-volume sequence of novels A Dance to the Music of Time evokes a similar feeling in James: “How I relished the actual physical experience of consuming his little books like plates of sweets and grapes as I sat on my garden terrace while the heat gradually went out of a long summer.” But there’s a pit within the fruit: notwithstanding that “the whole sequence is an almost unbroken stretch of genius”, parts of it are, James says, dull. So too are parts of Conrad, who ranks similarly highly in James’s estimation. Marlow — Conrad’s recurrent narrator (Lord Jim, Heart of Darkness) — “is a bore ... Conrad’s sole tedious creation”. Conrad’s Nostromo, “one of the greatest books I have ever read”, benefits from having “no Marlow in it: the narrator’s voice came through unfiltered by an intervening cloth of tedium”.

James’s powerful influence as a critic results, in part, from his willingness to treat popular culture seriously and on its own terms. “I have always been convinced,” he writes, “that a national consciousness is formed by secondary writing rather than by serious writing.” Apropos of which, James reveals with gusto how his daughter — “like a drug dealer handing out a free sample” — got him hooked on Patrick O’Brian’s Jack Aubrey novels about a 19-century naval officer. If “the Jack Aubrey books are merely entertaining”, James declares, “they are that at a high level”.

Part of James’s interest in Aubrey and CS Forester’s fellow fictional sailor Horatio Hornblower is their embodiment of “leadership, discipline, and carelessness of danger”. These characteristics draw James’s focus in the histories he reads, particularly those of World War II. Although “Britain would not have survived without” Winston Churchill, “the war would have been lost if he had been left to himself”. David Fraser’s biography Alanbrooke shows the powerful influence of Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke, whose skill at handling Churchill and the latter’s wilder schemes benefited from “having been brought up well-off and well-placed” enough to “fearlessly contradict his boss”.

That silvered quality didn’t put off the Americans, “normally suspicious of toffs”, and Alanbrooke’s successful working relationship with five-star general George Marshall was part of the joint Atlantic command that “shows what democratic nations can do when the chips are down”. The US interests James: “reading about American politics was as thrilling, and almost as much fun, as reading about Hollywood”. The two are combined in the figure of John F. Kennedy, and James relishes Sally Bedell Smith’s Grace and Power, “a chronicle of the JFK White House” that exemplifies “the Higher Gossip: always a suspected genre, because we tend to enjoy it too much”.

JFK — with his Camelot cool and “compulsive womanising” — is far from John Howard. James praises Howard’s autobiography, Lazarus Rising, as “adding to the essential literature which will help to explain to the next generation of Australians just how their nation has come to hold its exceptional position”. James, a self-described member of the “blue-collar left”, meditates here on Australian political discourse, criticising the “vocal white-collar left” and “Australian intelligentsia” for unsubtle demonisation of Howard.

The intelligentsia is, James thinks, doing a better job with the nation’s culture. In his praise for the great Australian formalist poet Stephen Edgar, James reflects “on how far the Australian cultural expansion has come” in his lifetime: “Any feelings of isolation that its intelligentsia once had … no longer fit the facts. Its film directors and actors, its singers and conductors, are everywhere … Even in poetry, a field which has no real commercial existence, there is an Australian presence in the world.” James spends a chapter, too, cheering the much-needed “rise to influence of women” in the film industry.

Latest Readings is a frank book. Like his recent Poetry Notebook, there is a feeling of summing up. But, echoing his latest poetry collection, Sentenced to Life, James writes more expressly about mortality here. He is constantly aware that “time is not infinite, even though the love of art might seem to make it so”. When “you start the slide to nowhere”, the “air is lit by a shimmering tangle of all the reasons you are sad to go and all the reasons you are glad to leave. It’s the glow of life: apparently simple, yet complex beyond analysis.”

Writers often have a final blaze of clarity — a flame that roars hardest before it blackens to a wick. In Latest Readings, every burning line of prose I read, I feel aloft and singed: lifted by the brightness of his spirit and pained by the coming of his death. There is some comfort, though: Clive James has, surely, earned his immortality.

Latest Readings

By Clive James

Yale University Press, 192pp, $29.95 (HB)

James McNamara is a writer and critic.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout