Christos Tsiolkas’s Damascus marks beginning of long road

Christos Tsiolkas’s new novel, an unflinching take on Christianity, is the work for which he will be most remembered.

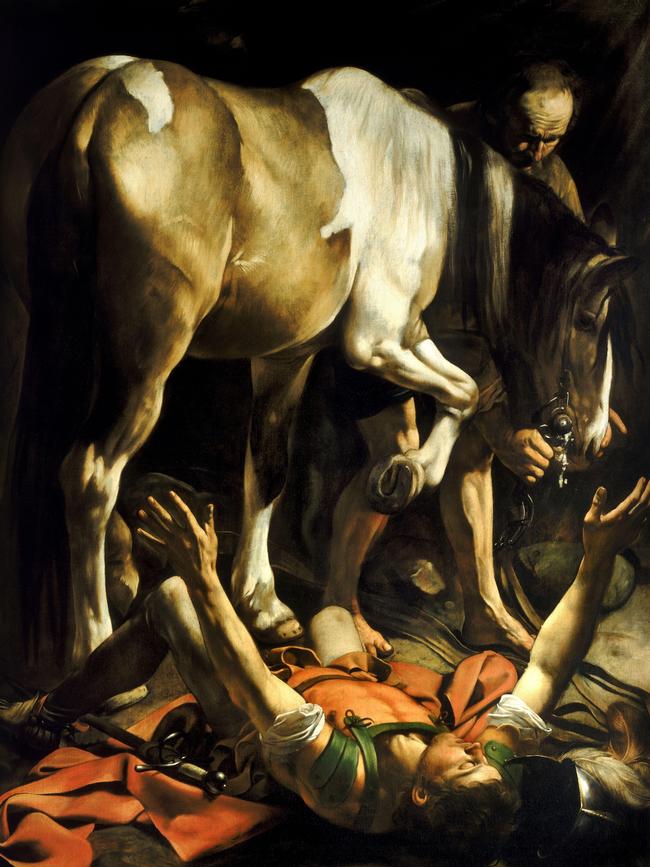

In 1601 Caravaggio painted Conversion on the way to Damascus, one of two panels he produced for the Cerasi Chapel in Rome. It depicts the moment Saul of Tarsus, a Pharisee who had devoted his life to flushing out and delivering retribution to early Christians, was struck down by the light of Jesus: who, in revealing himself to be the son of God, transformed Saul from persecutor into the Church’s first great proselyte.

It is a painting that takes the old iconographic rules relating to images of the Damascene conversion, a central and enduring biblical story culled from the New Testament, and turns them inside out.

The stagey formalism of his artistic forebears, with Christ pointing hard from his cloudy empyrean and obligatory soldiers looking on, is recast in intensely naturalistic terms. The divine light meant to emanate from the heavens is here narrowed to a radiance that fights smothering darkness to a momentary draw.

And it is dramatic, certainly: an image of violence barely contained, an electric scene wrenched from tenebral gloom. The ecstasy of religious conversion is, in Caravaggio’s vision, registered as something more abject and ambiguous. The future Saint Paul is as likely to be destroyed as transported by the experience.

How apt, then, that the publishers of Christos Tsiolkas’s latest novel – a narrative of shock and awe, fear and trembling, so large in ambition it will probably be the book for which he is best remembered – should choose this as the cover image for Damascus. Tsiolkas, too, has made a career from taking sanctioned narratives and flipping them to reveal a dark human underbelly.

Tsiolkas’s Damascus is not the front office record of early Christianity. It is a fiction that recognises sin as much as virtue, lust as much as pure elation, and doubt as often as faith. It is a novel that gives some of its best lines to worshippers of pagan idols, and figures the stolid, doubting Thomas, rumoured brother of Jesus, more than it does the crucified Christ.

This is not to say that the novel is concerned only with the history and sociology of the obscure Jewish sect that took over the Western world and changed the course of world history. Nor is it a secular dismantling of the potential grandeur of Christian faith, a tale in which revelation is depleted of its sacral aspects.

What it understands, along with the best modern representations of Jesus’s life and afterlife – works including Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel The Last Temptation of Christ and Pier Pasolini’s film The Gospel According to Matthew – is that salvation might be won through a public wrestling with doubt, and through a concentration on human acts of redemption, rather than on Jesus’s deity and divine grace.

In other words, Tsiolkas proceeds to tell the story of the early Church through the sorts of paradoxes that Jesus himself trafficked in, according to the authors of the Gospels. He finds the sacred in the mundane and holy spirit in the fallen, the diseased, the outcast.

This makes it a deeply uncomfortable read for those who have absorbed the canonical version of events.

There is brutality in these pages, depravity too. There is a concentration on the bitter factionalism that threatened the viability of the early Church, rather than a streamlined concordance – that straight line from Pauline teaching to contemporary Christianity that those raised in such beliefs have inherited.

We open, for example, with the stoning to death of a young woman, thanks to intelligence provided by the Pharisee Saul. He has tricked her into thinking that he shares her belief that the Jew known as Yeshua is actually the son of God. It is Saul who eggs other men on with stone in hand – and it is she, bitter and proud in her own sense of righteousness, who calls out that he without sin should cast the first stone.

Saul is a fascinatingly awful, ferociously divided figure in Tsiolkas’s telling. He takes the coins won from sending the girl to her death and uses them to get drunk and sleep with a male prostitute, little more than a boy.

He loathes his own proclivities; he despises his weakness and lust. And yet, he burns with certitude regarding the teachings of his sect, the group whose beliefs provided the foundations of rabbinic Judaism, as a bulwark against his frailties.

And that famous moment of conversion on the road to Damascus? The light is there, as is the voice of Jesus. But the flare of knowledge is bundled up in a more worldly act. Saul has been beaten and robbed and left for dead on the roadside, where his saviour is a man and his family whose religious beliefs have led them to return hatred with kindness; and when hit, to turn the other cheek.

Saul does not immediately accept the lesson these ‘‘Strangers’’ have to teach him; too much of his own residual sense of worth and identity is tied up in despising early Christians, those who disobey many Jewish strictures relating to purity and impurity, and whose social relations are defiantly non-hierarchical. Haltingly, however, and then eventually with the same absolute certainty that Saul bought to his time as a Pharisee, the man who became Paul – in the author’s view, the first Christian in a titular sense – set out to transmit the word of his messiah with a vehemence and eloquence that ultimately rescue him, in readers’ eyes, from the sins for which he is initially damned.

Paul’s genius was to recognise that putative Christianity was a universal creed, not an exclusively Jewish sect. It was egalitarian; it accepted adherents irrespective of ethnic origin or social class. As Paul himself wrote to the Galatians (an epigraph in the novel): ‘‘There is neither Judaean nor Greek, neither slave nor free, nor is there male nor female, for you are all one in Jesus Christ.’’

Tsiolkas follows him, not so much to the Jewish enclaves of Galilee but to the cosmopolitan cities of the Levant, Asia Minor and mainland Greece – even to Rome, where, in some of the most powerful pages in the novel, he switches perspective to a wounded old Roman soldier named Vrasas, whose job it is to oversee Paul where he is a prisoner of the Emperor Nero.

Vrasas’s voice is that of doubt and suspicion. He is worldly, unillusioned and has lived by the sword. He watches the old man and his visitors, primarily the handsome young Timothy, who would later be beatified as an apostle and constant companion to Paul, with scarcely concealed contempt.

They strike him as obscene in their mutual tenderness, as unforgivably effete.

Yet even Vrasas arrives at a grudging respect for Paul, a frail and broken old man who has evidently suffered greatly for his beliefs. Through him, we are able to view these saintly figures through a pagan lens. They could be madmen or fools from this perspective; their hopes for a return of their redeemer an act of madness disguised as fervour, their humility a sign of weakness in the face of the fearsome apparatus of the Roman empire.

Tsiolkas is careful to grant doubt to Timothy and Paul directly, as well. A constant refrain throughout the novel is a question: when will Christ return? They ask themselves the same thing.

As the chiliastic enthusiasm of the decades after Yeshua/Jesus’s crucifixion gives way to cold hard reality, we gain, via Tsiolkas’s creations, a sense that the Church itself – the sign of the cross, the breaking of bread and drinking of wine, the ritual refrain of amen – are rituals designed to keep open the utopian possibility created by their redeemer. Christianity, in other words, emerges out of the failure of Christ to return as expected. Christianity was the long game designed to keep the possibility of that return present in the minds of congregations in the millennia to come.

The novel’s chronological structure, which is fractured in time and place, circling backwards after having jumped all the way forward in time to 87AD in Ephesus, where Timothy’s final days are imagined, is analogous. Moments in which some small victory is won, when an apostle finds words fit to move a group of believers who are in despair, are followed by events, much earlier, that suggest total defeat.

The candle flickers and flares, but even in Tsiolkas’s resolutely irreverent telling, it is never entirely extinguished. At a crucial moment in the novel, we find Timothy, tired, aged and infirm, attempting to accommodate in words the very different beliefs espoused by his teacher, Paul, and his lover and friend, Thomas. Of Paul, he writes:

He took his staff and prepared to journey to the ends of the world, to proclaim that if we don’t have faith that the Lord truly knows our suffering, we cannot believe in a better world to come. And without this hope in a better world to come, then we are doomed to selfishness and greed and fear.

But of Thomas: ‘‘I write of his understanding that the meaning of our Saviour is to be found in his life.’’ Of those who look constantly beyond this world to the next, Thomas believed, ‘‘the Zealot’s declaration against the world (is also a declaration) against the beauty of the Lord’s creation’’.

That beauty is found in the faces of those most stricken by poverty and disease, in the face of a prostitute and in the face of the thief. That beauty is found in the face of both stranger and Israelite.

In an afterword to the novel, Tsiolkas writes of how his childhood faith was dashed by the growing awareness that his sexuality was abhorrent to church teachings. So it is a testament to his generosity of spirit that the author has worked so hard and well to understand those who refused to understand him.

The novel may be a profane medium – and this particular example may be replete with savagery and horror and secular scepticism – but ultimately Damascus reverences its subject.

At its best, which it is miraculously often, the novel is conjugated not in the simple present but in what is known as the ‘‘prophetic perfect”, a tense that, in scholar Lewis Hyde’s words, ‘‘bespeaks a perennial life constantly blooming in the present moment’’.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

Damascus

By Christos Tsiolkas. Allen & Unwin, 440pp, $32.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout