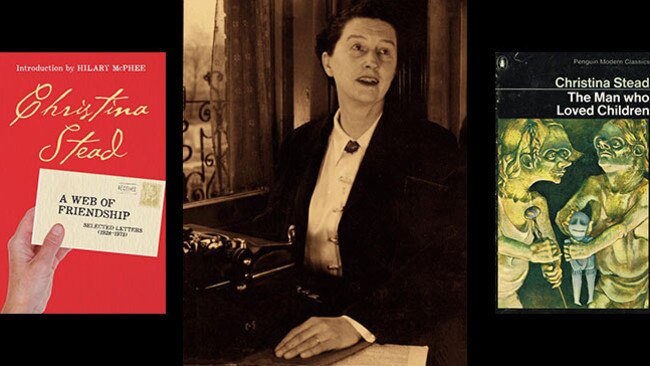

Christina Stead’s letters conjure the past and the future

Christina Stead’s letters, with their ‘awkward Australian bones’, conjure both the past and the future.

Christina Stead left Australia at the age of 26, arriving in England in 1928 ‘‘like a small insect waving its antennae’’. ‘‘I really hate work,’’ she wrote to her cousin Gwen. ‘‘I am not a born writer, but must say … I get the profoundest, most passionate satisfaction from writing and it is the only thing, since I am so thin, that keeps me from getting fretful under disappointment natural to living merely.’’

Words trip over words, you sense stories in the making. Her letters are performances, passionate narratives from life, bashed out single-spaced on second-hand typewriters with handwritten annotations.

The correspondence selected in a new edition of A Web of Friendship, preserved by family members, by agents and publishers, by writerly friends and literary acquaintances all over the world, is from Stead’s side only.

The letters she received were mostly destroyed as she and Marxist writer Bill Blake, her life’s companion, moved in and out of rented and borrowed accommodation across the northern hemisphere.

Between the wars and afterwards was a difficult time to be an Australian-born writer. Censorship was rife, publishing everywhere was conservative, with publishers rarely interested in manuscripts emanating from the colonies. Stead’s first London publisher, Peter Davies, didn’t ‘‘get’’ her books, or so it seemed to her, and paid royalties irregularly — but he did champion The Salzburg Tales and Seven Poor Men of Sydney in London and New York.

Simon & Schuster and Harcourt Brace in New York were more attuned to Stead’s dog-eats-dog dark comedies, her rapid shifts of pace in House of All Nations and For Love Alone — but the rest of them were ‘‘tripe merchants’’ recommending she emulate John Steinbeck and Hollywood tie-ins such as Gone with the Wind.

In Sydney, Angus & Robertson, then the only publisher of size in Australia, was the real villain as far as Stead was concerned — interested only in Australiana and potboilers, declaring her cosmopolitan novels too literary, ‘‘un-Australian’’. Stead and Blake, a German Jew raised in the US, much preferred Eastern European publishers, who translated and produced their novels in handsome editions. Also, ‘‘socialist publishers pay royalties’’, she told friends, the accrued funds in local currencies being spent on fine booze and books whenever they could visit.

Stead always insisted she invented nothing, embroidering, coding, making fantastical metaphors from the depths and heights of real life. She strongly disapproved of ‘‘Freud’s noisome fancies, mostly ridiculous, from literary work … I always want to say (but don’t usually) ‘But those things are real, friend, not sickly dreams’.’’

She blamed her father, a naturalist, for forming her, deforming her, giving her up to bad stepmothers who couldn’t love her, and she wrote David Stead no letters after she left. But The Man Who Loved Children, first published with little fanfare in 1940, enshrines her rage and love. Stead declared the book ‘‘terribly lifelike’’, and too painful for her to ever reread.

Her deepest friendships were always with men, their wives mentioned fondly but in passing. She first met American poet and critic Stanley Burnshaw in New York in 1933 with Blake, at the office of the communist journal New Masses. Stead responds at length and with great perspicacity to his work, and he always to hers.

‘‘You say the novel is spotted with some extraordinarily dull and gawky pages which look suspiciously deliberate,’’ she writes, ‘‘but I may as well say they are not deliberate, they are just dull and gawky on their own and it may be a long time, in fact, before I can eliminate these dull passages from my writing.’’

Her letters reflect that reciprocity so crucial between writerly friends — those who take the trouble to write a detailed analysis of the other’s work, who send each other advance copies, who ask their publishers to consider seriously the work of a writer they respect, who feel free to rage about the treatment they receive at the hands of their editors and critics.

Many years later, it would be Burnshaw, then vice-president of Holt, Rinehart and Winston, who saw to the pivotal reissue in 1965 of The Man Who Loved Children, and commissioned an introduction by the superb critic Randall Jarrell. Stead writes to Burnshaw that she approached Jarrell’s words

with the usual feeling of quiet nausea, fear too, which always puts me off the reading of criticism … With this I had the feeling one has about one who truly loves you — “How can it be? How can he love me? How puzzling.” … I had the same feeling almost — the perfect reader, the real reader. Who does one write for? Oneself — and the true reader … This is such a new and even pure sensation.

Reading between the lines of Stead’s letters, something of the difficulty of being an expatriate writer, published in London and New York with agents in both countries, and with a small or non-existent market subject to colonial royalties in Australia, can be understood. Those who lived for years outside Australia often suffered for their cosmopolitanism and subject matter.

Henry Handel Richardson and Randolph Stow never returned. Patrick White did but continued to be published first in London and New York. Stead, always scathing about the English class system, disliking the adulation of the Bloomsbury set and ‘‘the Virginia Woolf thing’’, craved an Australian readership, which was a very long time coming.

At first there were occasional mentions of favourable overseas reviews in the Sydney literary pages, which her cousin Gwen sent her. Nettie Palmer starts writing to her in 1935, passing on Rebecca West’s praise of Seven Poor Men of Sydney. The women had been delegates to the first International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture, a gathering of intellectuals against fascism.

Walter Stone, of the Book Collectors’ Society, in 1949 writes asking for publication details of her books in their various editions for his newsletter, which solicits a grateful reply from Stead, pointing out that Australia was the only country to ban Letty Fox the previous year, ‘‘caused by some highly coloured press stories in the Australian papers … with the idea of helping sales’’.

But it was the literary quarterlies Meanjin and Southerly, publishing occasional stories and commissioning critical articles, that began building her public. The magazines, dependent on small amounts of support from universities and the Commonwealth Literary Fund, could pay only pittances but she was fortunate in editors such as Clem Christesen, who at times provided substantial feedback. Stead hated being edited and was often late returning proofs.

Her correspondence is like a map of an emerging culture. Editors, writers and academics such as Nancy Keesing, Dymphna Cusack, Dorothy Green, Elizabeth Harrower, Mary Lord, Judah Waten and Michael Wilding start to seek her out whenever they are in London, and fret about the invisibility of her great opus. Their students are encouraged to read her, they include her in anthologies of new Australian writing and nominate her for fellowships and awards. Stead is heartened by the attention but is no pushover — railing at times about Australian literary criticism being ‘‘heavy fumy palimpsesting’’ and editors ‘‘who keep embroidering upon the authors’ MS (And must be restrained.)’’.

Not until after Blake had died did she return to Australia for a few months in 1969 — the recipient of a creative arts fellowship from Australian National University, category B for ‘‘an Australian expatriate artist of international repute’’.

Her novels were largely out of print here, unattainable even in libraries, but Australian literature was well on the way to being ‘‘discovered’’ and she found herself an Official Personage, interviewed, photographed, feted everywhere. It was all a great strain, she hated public speaking and she drank too much, but she loved the trees and the big skies and being driven from Canberra to Melbourne across the Monaro by her new friend Dorothy Green.

Professor RG Geering first wrote to Stead early in 1960, inquiring about her publishing history, and offering to act as a go-between with Angus & Robertson in an attempt to get paperback editions of her novels published in Australia. Her letter in reply is restrained but firm. He visits her in London a few years later. He is an academic, a species despised and ridiculed by Stead and Blake, but his respect for her work and his determination to have it republished were palpable and her reliance on him starts to grow.

‘‘Dear Professor Geering’’ quickly becomes ‘‘Dear Ron’’ and their friendship blossoms to the point where he eventually became Stead’s literary trustee, expert in the ways of ‘‘weaving a culture’’, as she put it, ‘‘tending the exotic plants in Australian literary gardens’’.

He and his wife Dorothy were kind and forbearing during the desperately lonely years after Bill’s death and it was Ron Geering who was left to place in the National Library a trunkload of loose ends and to collect the hundreds of letters she had written over half a century. Stead had earlier destroyed all her drafts, most of her private papers, diaries and intimate correspondence from family and friends. They, on the other hand, had kept hers.

‘‘I am a believer in love. That’s really my religion,’’ Stead said to an interviewer at the end of her life.

She saw herself as unlovable, fearful of being bereft of male company, craving passion and fearing rejection. Nothing but her letters, surely, could give us such a sense of her being a great writer, engaged in ‘‘the awful blind strength and cruelty of the creative impulse’’, reaching out, yearning for a true reader.

Now that letter writing is almost done for, the next generation of literary trustees will find themselves wrestling with very different gaps in the record and tracks in the algorithms. The outrage and struggle will still be there, the jokes and the gossip and the despair about government policy, fickle publishers, facile critics.

Literary biographers will have to pick their way through more self-censorship and self-promotion, more anxiety, perhaps. Writers who SMS are often indiscreet, sometimes at great length with paragraphs and punctuation in place, starting some of them with an OMG or a satirical emoji. Their emails tend to be more judicious or to include instructions — ignored mostly, I assume — to ‘‘burn this’’. The protocols are instinctive and evolving.

So it is no surprise that the bliss of reading torrents of letters left by writers gets ever stronger. You feel the presence of the past, the writer’s past, this country’s past, your own past — and you sense the future start to unfold. Stead’s letters, with their awkward Australian bones, their cosmopolitan sensibility and their ‘‘intelligent ferocity’’, cannot help but draw us in.

Hilary McPhee is a publisher, editor and writer. This is her introduction to a new edition of A Web of Friendship: Selected Letters 1928-1973, by Christina Stead (Miegunyah Press, $24.99).