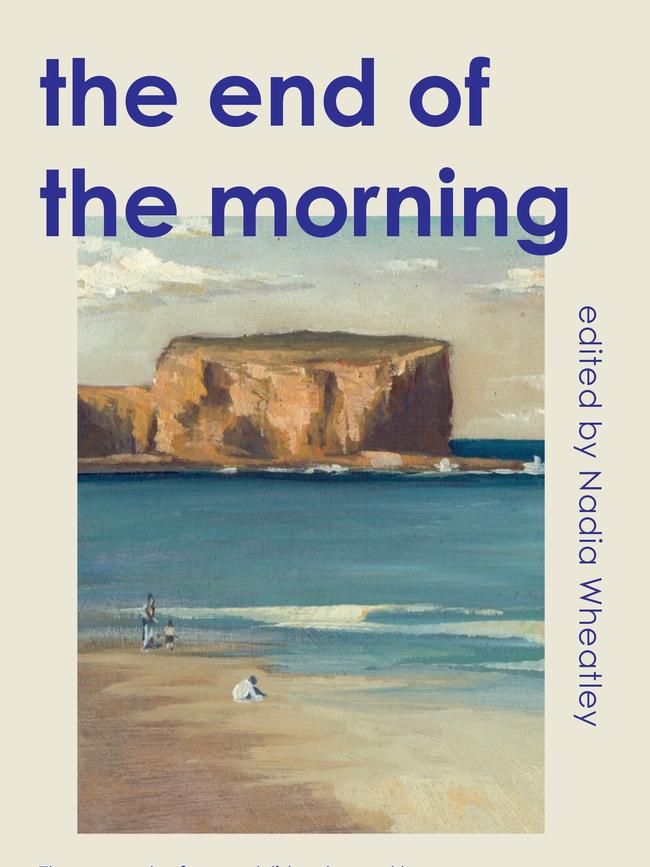

Charmian Clift’s unfinished novel The End of the Morning

Charmian Clift’s unfinished novel, The End of the Morning, proves she was as good as her feted husband — the difference was he had the space, time and grant money.

Nadia Wheatley’s 2001 The Life and Myth of Charmian Clift is a classic Australian literary biography. It retrieved the person; but her work did not immediately follow. Clift’s work remained out of print, overshadowed both by husband George Johnston’s oeuvre and her own literary legend.

For Wheatley and others, Clift’s writing became unfinished business. More than two decades later, their dedication has seen fruit in reprints. The variety and verve of her writing can now be widely appreciated. Her Grecian travel memoirs originally had modest sales, but now are translated, with a commemorative plaque for Clift at the island of Kalymnos. Sneaky Little Revolutions, Wheatley’s 2022 edition of Clift’s newspaper articles, sold out its print run – most rare for a writer both Australian and decades dead.

For this book, Wheatley collects again Clift’s nonfiction, but also fiction. In the literary marriage of Johnston and Clift, they first gained acclaim as collaborators, with 1949 novel High Valley. When My Brother Jack appeared in 1964 Johnston became a literary star, and Clift was his satellite. Even with the success of her journalism in Australia, her fiction seemed second-best.

Clift had deadlines to meet, while also wrangling a household, her children and marital problems. Nonetheless, she persisted – with a novel unfinished at her untimely death. It appears here in full for the first time, though long extracts from the manuscript figured in Wheatley’s biography.

The End of the Morning displays Clift’s typical writing skills: her liveliness, observation and acute sense of place. More specifically, it shows what she could do in fiction. If Johnston excelled at the autobiographical novel of Australian life, then so did she. The difference was that he had the space, time and grant money to complete a trilogy.

Clift only managed about 70 pages. Wheatley correctly realised they formed less of an incomplete novel than a fully realised novella. Jessica Au’s Cold Enough for Snow may win awards now, but half a century ago a novella was not a publishable book.

And yet “The End” is marvellous, a time-machine trip into the lost Australia of Clift’s childhood. She would return often, in various writerly forms, to her birthplace of Kiama, on the south coast of NSW. Here she and her siblings grew up free of modern helicopter parents and cosseting, running wild in beach and bush.

A supposedly happy childhood does not always bear close examination. While the setting was idyllic, the family were living through the depression. They never faced unemployment, but times were tight. The scarcity was also emotional, parental approval given to the favoured child, who was not Charmian nor her fictional Cressida. The most powerful passages in “The End” depict her bitter resentment.

Her Morley family had other tensions. The father handed his pay-packet over to his wife, but otherwise ruled the household, eccentrically. He had escaped the class wars of England via emigration, finding a niche that suited him perfectly. He got his work lunch delivered from home, and could piss on the fuchsia bush as he pleased.

In contrast, the more proper mother was a slavey, worn to a ravelling keeping the household going. She had her aspirations quashed, so lived through her children. Such a story was common, with frequently poisonous results. What if the child wanted their own life, even if disappointing the parents?

“The End” was a matter that Clift returned to, but could not resolve to her satisfaction. Partly it was because what other people might think; firstly, her mother. Another problem was that the real ending of Clift’s youth was tragic, with her illegitimate baby surrendered to adoption. It was a secret waiting to be revealed, something shocking even in the late 1960s. The effect on her newspaper readers could only be envisaged, with dread.

Yet another factor was even nastier. If Clift wanted to spare her mother’s feelings, then Johnston had no such considerations. He believed the greatest form of the novel was the autobiographical confession – a privileged life of art that was hell on family and friends. He fictionalised and appropriated his wife, even using the name Cressida Morley, a persona she had herself created.

As is now well known, as Johnston’s Clean Straw for Nothing neared publication, the couple were in crisis. Both were alcoholics with Johnston slowly dying. Clift felt unable to ask him about her depiction in the novel, and could not progress with “The End”. Wheatley significantly notes that Johnston’s Cressida was not a writer, maybe unconscious bias but surely insulting.

After a major row, Clift swallowed his sleeping pills, and so came the end of her night. The pity of it is that she died short of a more congenial era, whose reforms and active feminism would have suited her busy journalistic pen.

How good she was in her “colour pieces” is shown by the examples collected in this book. They range from the everyday to the activist: she illuminates the mundane moment, or argues for a better Australia. She sketches neighbours, protests the loneliness of the housewife, and revels in the natural world.

Likely Clift did not know the work of her 19th-century pioneers and precursors, American Fanny Fern (Sara Parton), or Mary Fortune, writing in Melbourne. They presented women’s everyday experience, for women, both engagingly and radically. All three wrote superb and vivid prose.

Clift had more opportunity, being able to join AWAS in wartime, or take tea with TS Eliot, or wine with Leonard Cohen. But she was still hideously constrained, to die at 46, with so much living left to do.

In another world she is still with us. She can be imagined as a sprightly centenarian, watching her granddaughter, Gina Chick, win Alone Australia, and reaching proudly for not a typewriter but a laptop. That was a road not taken, but the one she did left us some wondrous writing.

Lucy Sussex is a writer, editor and researcher

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout