Charlie Chaplin: the silent revolutionary

Charlie Chaplin rose from abject poverty to worldwide movie legend. But his later career was marred by persecution and exile.

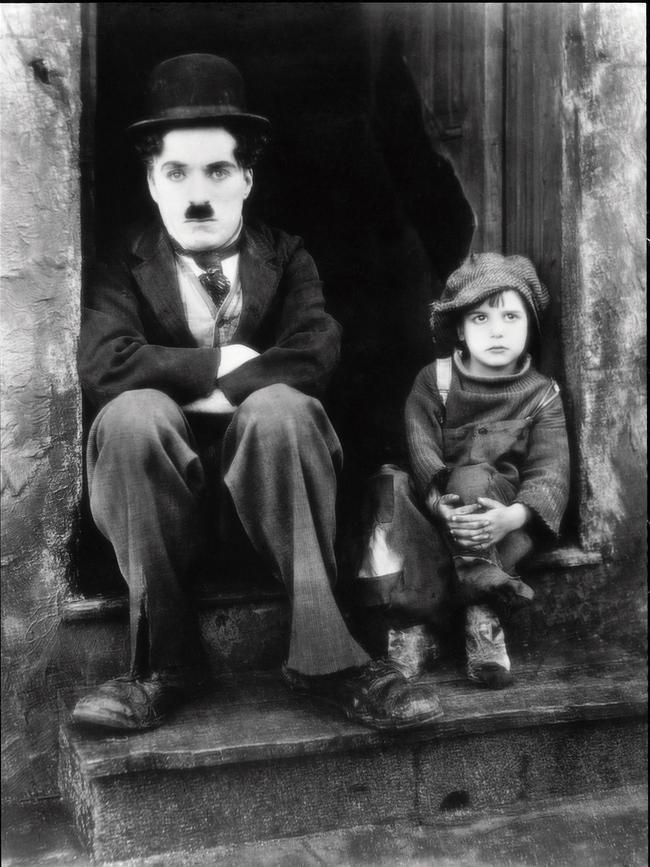

This year marks the centenary of the first feature-length film directed by and starring Charlie Chaplin, and The Kid triumphantly deserves its place in cinema history.

Still beloved by children the world over, Chaplin, despite his humble origins, was a renaissance man – accomplished comedian, actor, composer, writer – and business executive.

He was unquestionably one of the greatest entertainers of the 20th century.

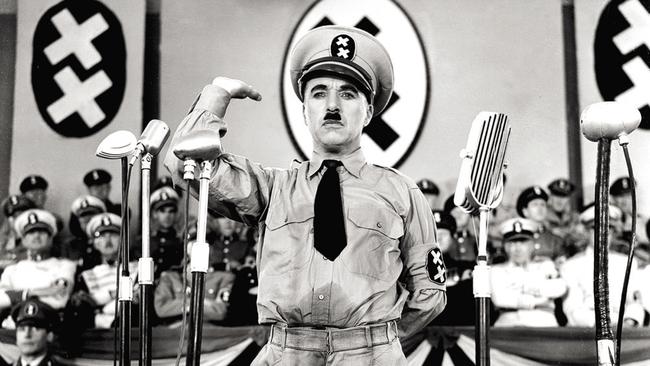

Charles Spencer Chaplin was born in Walworth, an impoverished London suburb, on April 16, 1889, five years before the first moving images were projected onto a cinema screen. His near contemporary, Adolf Hitler, who would adopt the famous Chaplin moustache, and who Chaplin would mercilessly parody in The Great Dictator (1940), was born just four days later. The 2003 documentary, The Tramp and the Dictator, provides fascinating parallels between the two men.

Chaplin’s father, also named Charles, was a minor star of the English music halls, known for singing the popular songs of the day. He was also an alcoholic, who separated from Charlie’s mother, Hannah, soon after the boy was born and died a few years later. Hannah was a music-hall chanteuse and she also drank to excess. Throughout his childhood, Charlie and his older half-brother, Sydney, were placed in a succession of orphanages and workhouses while their mother was hospitalised, eventually suffering what became a permanent mental breakdown.

The most famous comedian of silent cinema grew up in extreme poverty.

His success story is an epic in itself. He wrote in his autobiography that he first appeared before the public at the age of five when his mother suddenly lost her voice and he came onto the stage to finish her song. At the age of eight he became a member of a troupe known as The Lancashire Lads, and for a few years he played on the West End stage as Billy the Page Boy in a long-running theatrical adaptation of Sherlock Holmes. Eventually he became a star of the English music halls and travelled with the Fred Karno company for a tour of the US in 1910-11 and again in 1912-13. In 1913 he was invited to join Mack Sennett’s Keystone Company, which was celebrated for its production of slapstick comedies, and he arrived in Hollywood, at the age of 24, in December 1913. The first short film in which he appeared was titled Making a Living, in which he played a wealthy philanderer. But his second film, Kid Auto Races at Venice, was the first time he appeared on screen as The Tramp.

He assembled the costume for this character from the cast-offs of other actors: the trousers, far too big for him, had belonged to portly Fatty Arbuckle and the derby hat to Arbuckle’s father-in-law. He later said: “I had no idea of the character, but the moment I was dressed the clothes and the makeup made me feel the person he was.”

Over the years the character of The Tramp was refined; when he makes his final appearance in Modern Times (1936) he is deeper, richer than the little outsider who skidded frantically around corners on one leg being pursued by cops in the early days. The films Chaplin made between 1914 and 1920 are, for the most part, frenetic slapstick comedies typical of the period, the “custard pie” era of cinema. There were many other funny silent-movie comedians, notably Buster Keaton, but also Harold Lloyd, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, Mabel Normand, Fatty Arbuckle and Harry Langdon – but Chaplin was the one that audiences loved.

The Tramp was an immediate success with moviegoers around the world. Movies were silent, so language didn’t matter; from Stockholm to Tokyo, Rio to Montreal, audiences adored Charlie. They didn’t just laugh at him, they embraced him. He was the common man, the innocent, but he was also naughty and cheeky, and he thumbed his nose at authority – pompous officials, especially police officers, get short shrift in Chaplin comedies.

From April 1914 Chaplin was permitted to direct his own material. Commencing with Twenty Minutes of Love, the actor-writer-director made dozens of classic two-reel (roughly 20-minute) comedies over the next five years, making him one of the most famous men in the world.

Classics like The Floorwalker and The Pawnshop (both 1916), Easy Street and The Immigrant (1917) and his anti-war comedy Shoulder Arms (1918) are just a few of the many laugh-packed entertainments he devised.

But in the process he made enemies. It is said that J. Edgar Hoover was especially incensed by a scene in The Immigrant where, as the ship bringing refugees from Europe sails past the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbour, the hapless immigrants are roped off and corralled as though they were cattle. Hoover, and others in authority, came to believe that Chaplin was a socialist, or worse.

And his private life was chaotic, even scandalous by the manners and mores of the time. Back in 1972, I spent an evening with veteran director Raoul Walsh who was a close friend of Chaplin during his first year in Hollywood; in what must have been a crazy, hedonistic environment Charlie, Walsh remembered, sowed plenty of wild oats.

In 1919 Chaplin became one of the four founders of United Artists, a major production and distribution company (the other founders were actors Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks and director D.W. Griffith).

Chaplin followed The Kid with a trio of short films before he made his second feature-length film, and A Woman of Paris (1923) was a surprise. For one thing Chaplin did not star in it, and for another it was a sophisticated romantic comedy and not a slapstick farce. Reactions at the time were mixed and Chaplin withdrew the film, eventually re-releasing it in the mid-1970s, when it was greeted with enthusiastic acclaim. Its Australian premiere was at the Sydney Film Festival.

By this time Chaplin had dramatically slowed his output. In 1916 he had directed and starred in 10 two-reelers; after The Kid he would take up to four years to complete each feature film.

The Tramp returned in The Gold Rush (1925), an elaborate dramatic comedy based on the experiences of Yukon gold prospectors. In 1942, Chaplin added a music track – he invariably composed his own music scores – and reissued the film with a somewhat superfluous commentary.

The Circus (1928) was the last Chaplin feature produced in the silent era and with the coming of the “talkies” Chaplin was faced with a dilemma: while audiences quickly rejected silent films in favour of the new sound films, he was certain that The Tramp would not be accepted if he spoke, especially since Chaplin had a distinct English accent. For this reason he bucked the trend and released arguably his finest film, City Lights (1931), as a silent film, a good three years after the talkie revolution had transformed the cinema.

Modern Times (1936) was essentially a silent film also, and the first time Chaplin spoke on screen was as the Hitler-like Adenoid Hynkel in his savage satire, The Great Dictator (1940). This film created more controversy for Chaplin because it was released just after the outbreak of war in Europe. Isolationists were in powerful positions in America at the time. It so happened that a few other anti-Nazi films were released in 1940, most notably Foreign Correspondent, the second American film directed by Alfred Hitchcock who, like Chaplin, was British. Some demanded to know why these foreigners were using popular culture to indoctrinate the American people.

It didn’t help that the following year saw Chaplin embroiled in a messy paternity suit with a woman 30 years his junior, or that he saw no reason not to appear in public and make what some considered inflammatory speeches: when he spoke at a San Francisco benefit for Russian War Relief he addressed the audience as “comrades”.

His first post-war feature added to his woes. With Monsieur Verdoux (1947) he abandoned The Tramp altogether (even The Great Dictator had featured the Tramp-like “Barber”, so that Chaplin had played two roles in that film). Verdoux, inspired by the career of the French serial killer Landru, also known as Bluebeard, was unlike anything Chaplin had attempted before and he had considerable trouble getting the screenplay cleared by the Breen Office – the censorship board. Breen took particular exception to “sections of the story in which Verdoux indicts the “System” and the present-day social structure, without mentioning that the film was taking place not in the US but in France between the wars.

The notorious Hollywood hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee had commenced and Chaplin – who had made the mistake of never taking American citizenship (“I am a citizen of the world!” he once proclaimed) was under attack.

Nevertheless he managed to complete his last film in America, the nostalgic Limelight (1952), a leisurely, poignant tribute to the British music halls where Chaplin learnt his art. He plays an ageing, alcoholic comedian who becomes infatuated with a young dancer (Claire Bloom).

A wonderful climactic scene teams Chaplin with the other legendary comedian of silent cinema, Buster Keaton.

In September 1952 Chaplin sailed from New York with his wife, Oona, and four of his children to attend the London premiere of Limelight. While he was at sea the attorney-general ordered that “if and when he returns” he should be held by immigration authorities. The reason given was that “he has been publicly charged with being a member of the Communist Party and with grave moral charges and with making statements that would indicate a leering, sneering attitude towards a country whose hospitality has enriched him”.

He would direct two more films, both in London. A King in New York (1957) is an intermittently funny but bitter comedy about an exile, and the depiction of McCarthy-era America as a paranoid, ugly society is devastating. His final film, made for a major studio – Universal – was a major disappointment: A Countess from Hong Kong (1966) starred Marlon Brando and Sophia Loren with neither actor seeming comfortable in a strangely stilted shipboard romance. The brightest moment in a generally tedious movie was when Chaplin himself made a guest appearance as a waiter thrown off balance by the rocking of the ship. This brief cameo amply demonstrated that, as an entertainer, the old man had lost none of his skill and timing.

Chaplin and his family settled in Switzerland. He returned to America only once, in 1972, long after the anti-Communist witch-hunts had become a thing of the past.

The occasion was to receive a special Oscar awarded to him for his contributions to the cinema.

The Kid is screening in selected cinemas and will be followed by all of Chaplin’s subsequent features, except for A Countess from Hong Kong, in the coming months.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout