Catherine de Saint Phalle’s novel in running for Stella Prize

Catherine de Saint Phalle’s first book of nonfiction was this week shortlisted for the Stella Prize.

Imagine growing up among the French aristocracy with eccentric parents, romantically involved in an endless pas de deux, who in everyday talk, as though it’s a matter of immediate concern, revisit the Versailles of Louis XVI, the Greece of Odysseus, the Rome of the ancient emperors, the Carthaginians and the French Resistance during Word War II.

Your father is an imaginative storytelling banker whose fortunes ebb and flow. He is considerably older than your mother. She is a lady, not quite of leisure, because her neurasthenia keeps her fatigued, on edge, and unpredictable.

Imagine you are an only child in a world of adults, knowing there is something not quite right with your tiny nuclear family because everything jars and strains when ancient aunts, awkward cousins and hitherto unknown siblings arrive to visit. Your mother’s friends are a band of gifted fringe-dwellers; your father has none. The nuns refuse to educate you. Your father disappears for entire weekends.

Imagine that slowly, over the course of your childhood and adolescence, family secrets emerge, tangentially, entangled in revelations about Briseis, Alexander the Great, Marcus Atilius Regulus, Marie Antoinette and the rest of the historical characters that populate the endless, thought-provoking conversations you have in your mother’s bedroom, or walking with your father, your hand ensconced in his.

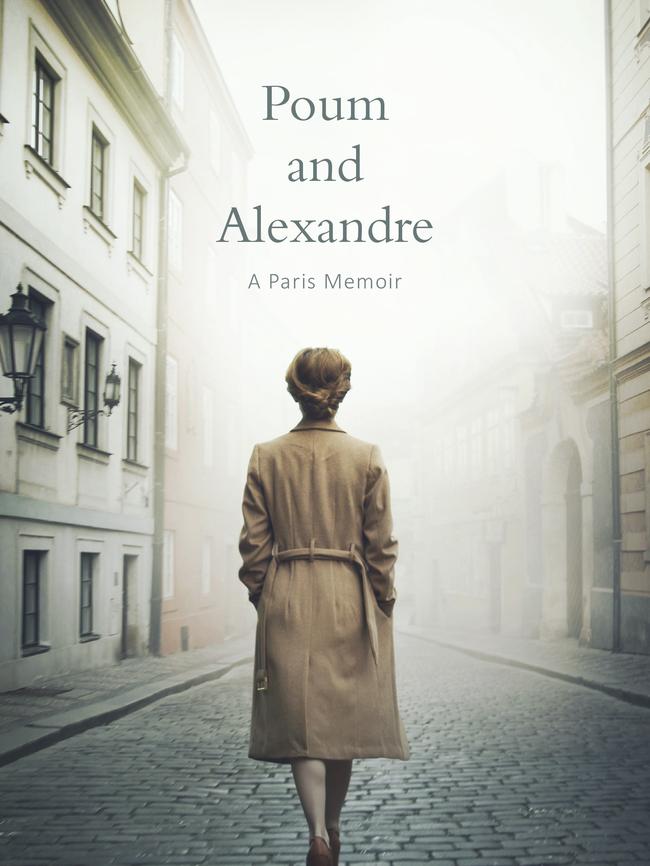

Now imagine you grow up to be a writer of such evocatively poetic prose, you are able to conjure convincingly all the moods, the faultlines and the pervasive sexual ambience of those times. This is what Catherine de Saint Phalle, who now lives in Melbourne, has achieved with her first book of nonfiction, Poum and Alexandre: A Paris Memoir, which was this week shortlisted for the Stella Prize.

It is a bildungsroman of intriguing dimensions. Saint Phalle was born in London, where she immediately became a British citizen. Her father, the Count Alexandre de Saint Phalle, came from a family that claimed to be the 13th oldest in France. He admired the Magna Carta, however: so much so that he insisted his daughter be entitled to its freedoms.

He had lived in New York for a while, but returned to defend his country when it was invaded, joining the Resistance and sniffing at the Johnny-come-latelies who claimed to have belonged, especially ones who covered their shame afterwards by hounding the Frenchwomen who fell in love with, or sought protection from, the occupying German soldiers.

Her mother, with her distant gaze, swings between inertia, in bed with her books, and restlessly roaming the streets of Paris on small but potent errands. She was called Marie Antoinette by her French mother and Spanish father, but everyone calls her Poum. She had a Russian great-grandmother. Denied the comforts of the church, belief still runs deep within her and she crosses herself automatically when she is unnerved, which is often. She is minutely conversant with lives of the last Bourbon kings and especially of the doomed queen whose name she carries. She can recite whole verses of the Odyssey, and reads and re-reads the Old Testament. She is also a kleptomaniac.

“Maybe she knows her whole being can fall apart at any moment,” her daughter writes, “and all the king’s horses, and that all the king’s men couldn’t put her back together again.”

Her father is more comfortable in his skin, as the French say. He is portly, though capable of considerable agility when necessary, and smells of the honey he consumes in great quantities for his health. He was the centre of Catherine’s childhood and adolescence, by her account, and she follows him everywhere, believes him implicitly, and is a willing accomplice in his sophisticated adventures.

It is impossible to describe more without spoiling the suspense. A gentle tension holds Saint Phalle’s chapters together, even as they unfold elegiacally. She seems to meet the slow drama of emerging truths, erratic though it is, with bravery and implicit trust — in her father at least. One hopes her rose-coloured view is sincere and not a calculated fabrication, because it can’t be entirely true. At one point she describes her father’s distress at being portrayed as a money-hungry capitalist, hunched over a pot of money, by his niece, the artist Niki de Saint Phalle. As usual, the moment is defused by a joke shared with his wife, who laughs to the point of tears. When he encounters Niki some time later, he embraces her warmly. He tells his daughter afterwards that Niki is, after all, the child of his brother.

In a recent New Yorker piece on Niki de Saint Phalle a more terrible reality emerges, and branches of families are rarely immune from each others’ demons. Niki, who became an art world celebrity in the 1960s and died in 2002, spent years in an asylum. At just a few months old, she was left at her grandparents’ chateau in the country when her father, Andre de Saint Phalle, also a financier, took her mother and older brother with him to New York. She rejoined the family when she was three years old, but the article describes this as the first of many abandonments. The household was luxurious but discipline was strict to the point of cruel. Her father sexually assaulted her. Two of her siblings committed suicide in adulthood.

Catherine de Saint Phalle, too, was sent away when she was little, to live with the family of her English nanny Sylvia, who was the practical foundation of her life. “Mummy Joyce” and “Daddy John” spring to life in her prose, and she underlines how devoted she became to her de facto grandfather. Yet the separations, first from her parents, then from her foster family, pass without comment.

This is not a criticism of the book. We construct and reconstruct our personal histories in ways that work for us. Saint Phalle’s book is thought-provoking and beautiful to read.

Its mystery and elegance, the red threads of exotic history narrated by her parents, and the author’s close examination of shifting manners and morals create a shadow world that is difficult to emerge from when the last page is done.

Miriam Cosic is a journalist and author.

Poum and Alexandre: A Paris Memoir

By Catherine de Saint Phalle

Transit Lounge, 288pp, $29.99