Catherine Breillat: #MeToo ‘worse than McCarthyism’

French film maverick Catherine Breillat refuses to judge a character who has sex with her teenage stepson. Oh, but what about if the sexes were reversed? Breillat has a bright response to that.

It’s a bitingly cold January day in Paris – the sky is low and grey and snowdrifts linger on car windscreens and pavements of the city’s elegant eighth arrondissement. These chilly conditions do not prevent Catherine Breillat from turning up for this interview in a wool mini dress and punkish calf-length boots, with her legs tanned and bare.

The novelist and film director is 75, and her stylish outfit could be read as a gesture of defiance towards assumptions about how older women should dress in a European winter. That impression is heightened as Breillat makes her way into a hotel suite with a walking stick and pronounced limp and slowly settles herself into an upholstered chair.

Labelled as an agent provocateur and cinematic maverick because of the way her films challenge conventional sexual mores, Breillat grapples daily with the side-effects of a stroke she suffered in 2005. With a bluntness that borders on self-laceration, she recently told Le Monde: “It’s very unpleasant to be crippled and to see that people think of you as a toad, old and ugly’’.

The novelist and creator of films including A Ma Soeur and the autobiographical Abuse of Weakness, starring Isabelle Huppert, is neither toadish nor ugly, but she has clearly often felt marginalised since becoming a self-described “invalid”.

Yet she has stormed back into the epicentre of the European film industry with her first film in 10 years – the taboo-up-ending Last Summer. This story of a feminist lawyer who has a secret affair with her 17-year-old stepson earned a standing ovation at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, was nominated for the Palme d’Or and was short-listed for four Cesar awards (France’s equivalent of the Oscars) including the prestigious best director accolade.

Last Summer is based on the 2019 Danish movie Queen of Hearts, in which a middle class woman behaves in a predatory way towards her stepson and lies about it – with devastating consequences. In a crucial difference, in her adaptation, Breillat shifts the focus from sexual predation to what she calls “the love drive”, without condemning her female protagonist, even though her semi-incestuous affair could ruin her marriage, family, career and her stepson’s fragile relationship with his dad.

“I don’t judge my characters!’’ she declares during this roundtable interview in France. “They (critics of the film) want the stepmother of the boy to have intervention and to be punished – I am not a judge, I am not an assistant social (social worker) – I can make a film without morality.

“It’s for people to have their own thoughts about what is moral, what is a fault, what is not such a big fault. You have to be free to judge. … I loved my characters. If people think it’s a love story, it’s irresistible, so it’s not scandalous. Life is like that.’’

Breillat has long courted controversy with her uncompromising views and insistently frank depictions of sexuality, desire and violence: she has used a porn actor in two previous films and has sometimes been described as a “porno auteurist”. While she believes the #MeToo movement has led to improvements for women working in film, she claims the extremes of this reckoning have led to an “awful period. This extremism is worse than McCarthyism’’. Nor is she a fan of intimacy co-ordinators, at one point calling them “stupid” and comparing them to the Taliban.

Last Summer will screen at the Alliance Francaise French Film Festival, which opens in Sydney and Brisbane on March 5. The festival is the biggest showcase of contemporary French film outside France and sold an astonishing 176,000 tickets last year.

This year, its line-up of 42 films includes prize-winning, period and blockbuster movies – artistic director Karine Mauris describes them as “the best of the best” of recent French cinema. The festival, which opens with a lavish $115 million adaptation of The Three Musketeers, will take place in 15 locations, including the state capitals, Canberra, the Gold Coast and regional towns Bunbury, Byron Bay and Victor Harbour, between early March and late April.

The festival’s website says that Last Summer “portrays the attraction and desire between stepmother and stepson, and the legal and moral barriers it threatens, with the fearless combination of social critique, dark humour and uncomfortable detail that has established her (Breillat) as one of the world’s most confronting – and essential – contemporary filmmakers’’.

Review asks Breillat whether she could have made the same film with the genders reversed – with a stepfather having an affair with his 17-year-old stepdaughter, without the stepfather being judged. “Of course,’’ she says brightly. “Me, my problem is not to change the morality of women, but to open the eyes to what (desire) exists. The morals I don’t care (about), but what exists, that is interesting.’’ The director, who co-wrote Last Summer’s screenplay with Pascal Bonitzer and Maren Louise Kaehne , expands on her philosophy of desire in the film’s production notes. She says: “Moralistic art constricts people and makes them ugly. But art is moral, because it makes people beautiful; it looks at them in a way that brings them into bloom and transfigures them … I am interested in desire, love, the love drive, guilt. In short, everything that eludes us, that has to do with the unsaid.’’

The film opens with the lawyer, played by Cesar-nominated French actress Lea Drucker, questioning a teenage victim of sexual assault and warning her the defence will try to portray her as a “world class slut”. In court, declares the gun child protection advocate, the victim inevitably becomes the accused.

Anne chafes against the strictures of her comfortable bourgeois life as a mother of two adopted girls and wife of an older, decent man. “Normopaths … bore me shitless,’’ she says, and during one reckless summer, she allows herself to fall for her equally restless stepson, Theo, played by teenage actor Samuel Kircher.

As he moves in with Anne and his father and stepsisters, Theo behaves like the classic teen nightmare – sullen, rude and lazy, he robs his father’s house and lies about it. He announces that “feelings aren’t my thing’’ when speaking of sex with a casual girlfriend. His young stepsisters, on the other hand, draw out his latent tenderness and Anne starts to bond with him.

It is Theo who initially seduces Anne and for a time, the pair exist in an erotic bubble, outside time. But when the mother and lawyer is confronted with the fallout from this illicit liaison, will she fess up or lie to protect her marriage, job and reputation?

Breillat makes no bones about the youthfulness of Kircher, whose skinny, shirtless torso accentuates how he has not yet fully grown into his adult body. “One morning he took his high school final exam, and in the afternoon, he had his first love scene!’’ she has said of the now 19-year-old actor. “They (Kircher and Drucker) never recoiled from the camera, and the camera was absolutely in love with them. The beauty of their relationship stems from that defencelessness and incredible purity.’’ Both actors earned Cesar nominations for their performances.

Breillat says “Last Summer was very well presented in France’’ and that this contrasts with a lack of domestic recognition for her earlier films, which “was awful’’. “My movies sell all over the world,’’ she says, speaking in English and largely dispensing with the services of the interpreter engaged for this interview. The director maintains she has had a “not very good career in France, but very good outside. It’s because of the foreign countries that I have been able to stay and continue to be a filmmaker”.

There was reluctance to finance Last Summer from some parties in France and the director adds with a conspiratorial laugh: “I suppose as I have not made a film since 10 years, they think I am a has been.’’ While Last Summer has no shortage of sex scenes, they are less explicit than in her previous films. She says that when filming such scenes, “it’s not the body which is important, it’s the emotion. My definition of me as filmmaker is that I am a director of emotion.’’

Drucker says some aspects of the movie’s forbidden relationship may be Anne’s fantasy. According to the actress, “there is something tragic, dangerous, and dizzying about that story. I couldn’t find all the answers, and that uncertainty intrigued me”.

The script, she says, sometimes “seems to stray from realism. One could indeed say that the story is only happening inside this woman’s mind’’. For the most part though, the film seems to be a work of realism.

As mentioned, Breillat opposes militant feminism. She is particularly upset by those activists who she believes are pushing a censorship agenda. “#MeToo is a great movement for the liberation of women,’’ she says, “but some extremist feminists want to take the power and to say, you cannot shoot that, you cannot! We have to refuse. Me, I am feminist of the first hour – but not an extremist feminist … It’s better to be an artist. ’’

She raises the issue of intimacy co-ordinators who choreograph love and sex scenes, launching a ferocious attack on them that lasts for several minutes. “What is a co-ordinatriss of intimacy?” she asks rhetorically. “It is not a profession … they have no competence.’’ She watched a documentary on this growing niche industry, which developed in the wake of #MeToo complaints from actresses who felt they had little or no control over how sex scenes were shot. “They never speak of cinema,’’ Breillat says, before likening intimacy co-ordinators to a Taliban minister who compared women to a jar of honey.

The notion of intimacy co-ordinators, she fumes, is “stupid and disgusting. It is evil for the actor who wants to make art.’’ “It’s too much!’’ she continues, claiming that touching an ear these days involves an intervention “to explain to the actor’’ how it should be done. She also protests that in some films, actors are only allowed to kiss on the cheek.

Through her excavation of forbidden desire in Last Summer, she is exploring “how we are’’, not how activists “want us to be’’. She describes the insistence that artists should portray only the latter as “totalitarian” and a form of “fascism’’.

Breillat makes these controversial comments as French cinema is rocked by a belated #Me Too reckoning over allegations of sexual assault – including assault of underage actresses.

France’s Culture Minister Rachida Dati last month called out a “collective blindness” towards sexual abuse that had persisted “for years” in the French film sector. French actress Judith Godrèche received a standing ovation at the César Awards ceremony on February 23 as she criticised a culture of sexual violence, “denial and privilege” within her nation’s film industry.

Godreche has accused disgraced Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein and two French film directors of sexual misconduct: she claims one French director started a “predatory’’ relationship with her when she was 14 and he was 39. The French directors deny these accusations.

Meanwhile, screen legend Gérard Depardieu has been charged with rape and accused of sexual harassment or assault by more than a dozen women. The Cyrano de Bergerac star denies the allegations and his supporters say he is the victim of a #MeToo witchhunt.

In past years, Breillat’s transgressive approach to sex and relationships has provoked resistance from official censorship bodies. Her first film, A Real Young Girl, about the sexual awakening of an adolescent (played by then 20-year-old Charlotte Alexandra) was released in 1976 and drawn from her novel, Le Soupirail (The Whisper). It was banned in many countries for more than two decades.

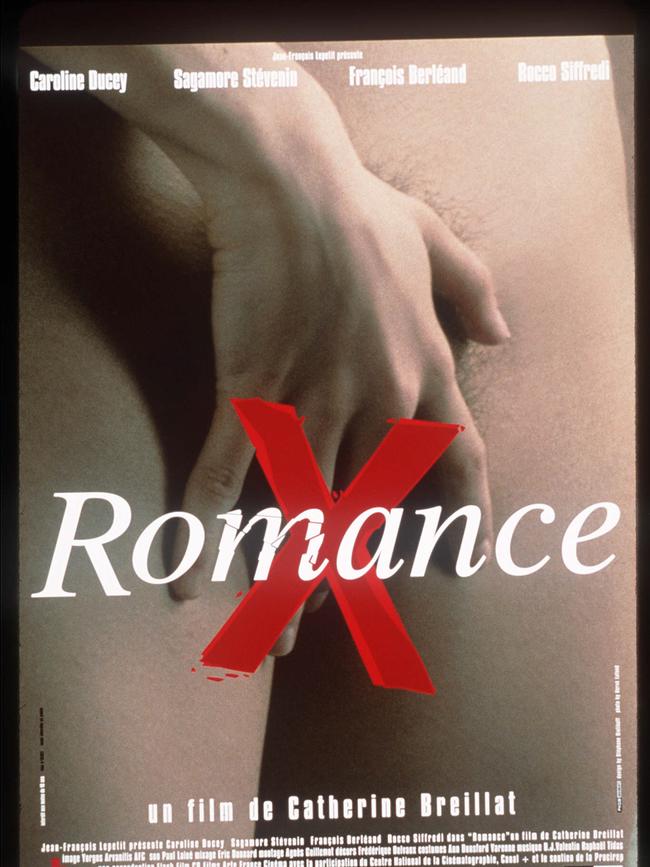

She cast porn actor Rocco Siffredi (known as the Italian Stallion) in her films Romance (1999) and in 2004’s Anatomy of Hell, while Sex is Comedy (2002), was, as its title suggests, a comedy about a female director who struggles to get two bickering actors to perform a satisfactory sex scene. That film’s director character uses the quintessentially Breillat-esque line: “Being afraid of being obscene makes one obscene.’’

While she is primarily a writer and director, Breillat has worked on the other side of the cameras, making her film debut as a dressmaker in Last Tango in Paris.

In 2005, she suffered a cerebral haemorrhage, which triggered the stroke that paralysed her left side. After a painful rehabilitation, she met a conman and offered him a prominent part in a film she intended to make. Over the next 18 months she gave him a screenplay grant and loans worth $1.1 million.

Years later she would allege the conman had taken advantage of her vulnerability following the stroke, and he was jailed in 2012 for financial abuse. In 2009 she wrote a book, Abuse of Weakness, about this traumatic episode and, four years later, she turned it into a film of the same name starring Huppert.

Part of Breillat’s mission in making Last Summer was to reverse gender norms. For decades, this auteur has worked in a field where, she says, female actors are considered old “and awful” after the age of 35.

“The youth can be in love with an older man, but not with (an older) woman,’’ she says.

“I show the contrary (case). ... It’s why a director of film is so important, because I transfigure also my actors. They become so beautiful when I look at them because l love them.”

She denies she set out to unsettle audiences with Last Summer’s ambiguous morality. Her voice rising with indignation, she says: “I make my film because I feel I have to do that, and I am always very surprised when people are condemning me.’’

The Alliance Francaise French Film Festival opens in Sydney and Brisbane on March 5. It continues in all state capitals and regional centres through March and April.

Rosemary Neill flew to Paris with the assistance of Unifrance.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout