Carrol Jerrems’ quest for meaning in the 1970s

The 1970s images of acclaimed Australian photographer Carol Jerrems – who died aged just 30 – continue to shape our visual culture.

Carol Jerrems is one of the most important Australian artists of the 20th century. This is a considerable accomplishment for a woman who worked at a time when photography was not widely considered art.

Despite a condensed career [tragically, Jerrems died in 1980 aged just 30] her work was substantially exhibited and published in her lifetime. She received numerous awards and in 1971, shortly after she finished art school, a number of her prints were collected by the newly established Department of Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Her work has been the subject of several significant surveys since her premature death, including exhibitions presented by the National Gallery of Australia in 1990 and 2012.

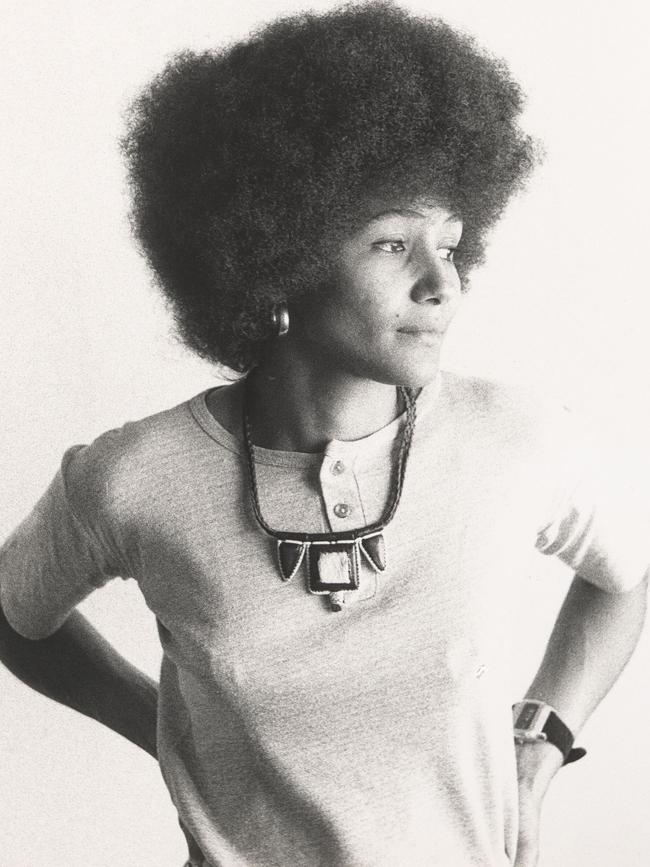

The National Portrait Gallery exhibition, Carol Jerrems: Portraits, is the first to position Jerrems’s practice around portraiture. [This exhibition features more than 140 photographs and includes portraits of leading cultural figures, including Anne Summers, Roberta Sykes, Evonne Goolagong, Red Symons and Shirley Strachan, as well as Jerrems’s friends and peers.]

Jerrems often called her work portraits. This idea may seem obvious because her photographs, taken over 12 years between 1968 and 1979, are almost always of people.

However, the notion that she produced portraits, and what this might add to an understanding of her practice, has slipped to the periphery. Curators have variously argued that her photographs “define a decade in Australia’s history” and are “emblematic of a particular moment in Australian culture”.

Among her early work, we find delicate preludes to some of her most famous images produced in the mid-1970s, including the now-iconic Vale Street (1975), a portrait of her friend Catriona Brown and students Jon Bourke and Mark Lean.

In Boy watching a man play billiards (1970), it is the young boy leaning, arm akimbo, behind the older man playing pool who is the focus of the image. He not only portends the stance of Bourke five years later, but also appears to exude a performance of youth and emergent masculinity that would find resolved expression in Vale Street.

Jerrems graduated from Prahran Technical College in 1971. The most important project she undertook in her first years after graduation was A book about Australian women, published in late 1974. Made with artist and writer Virginia Fraser, it is one of only two books produced in Jerrems’s lifetime for which she specifically created an extended set of images.

A book about Australian women contains 131 black-and-white portraits. Jerrems wrote in an introduction: “Each portrait is honest … The women are not intended as an elitist minority group, like a who’s who; some are well known, others are not; each is of equal importance.”

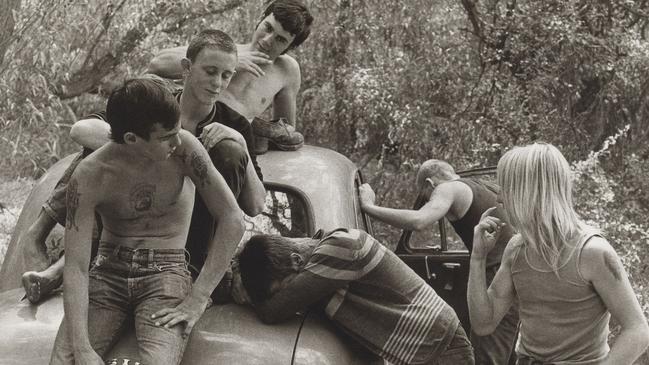

When A book about Australian women was published in 1974, Jerrems was living in Melbourne and teaching at Heidelberg Technical College, a notoriously rough boys’ school. Jerrems befriended and photographed a number of her students, which brought her into the circles of the working-class suburban youth subculture known as sharpies: teenage gangs with specific codes of dress and hairstyle who raucously followed Australian bands including Skyhooks and Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs.

It was during the mid-1970s that her most recognisable and celebrated photograph, Vale Street, was made. There are very few images in the history of Australian photography that are as captivating and transcendent as this single frame.

Its visual magnetism, strong feminist narrative and social documentary style were immediately compelling – including for museum collections making preliminary photo media acquisitions at that time. The final image quickly came to be seen as embodying new ideas of countercultural identity, gender and sexual propriety still emerging in the ’70s.

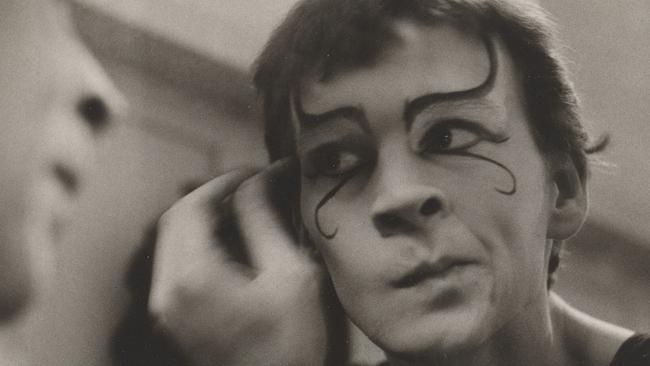

Jerrems’s navigation and portrayal of a more sensitive and introspective masculinity is apparent in images such as Letter and Les McClaren (both 1973) or the head and shoulders portrait of her friend and mentor, filmmaker Paul Cox (1976) made years after he had taught her at Prahran.

In 1979, Jerrems left Sydney and was living in Hobart teaching photography at the Tasmanian School of Art. In June she was admitted to the Royal Hobart Hospital, where she was diagnosed with a rare illness, Budd-Chiari syndrome, the condition that would result in her death in February of 1980.

She spent more than three months as a patient in Ward 3E, and began her last series of work there, documenting the effects of the illness and subsequent surgery on her body in a set of self-portraits made in a bathroom mirror. These are both matter of fact and shocking in their revelation of the aggressiveness of her disease.

She wrote a diary, The Patient, during the extended period of medical care and in the period following, reaffirming, “it is important to me to be continually working at photography. It gives meaning to my otherwise futile existence … My work is very important to me. Without it, I can’t really be happy, I’m incomplete.’’

Carol Jerrems: Portraits opens on November 30 at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra. This is an edited extract from the monographic publication Carol Jerrems: Portraits.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout