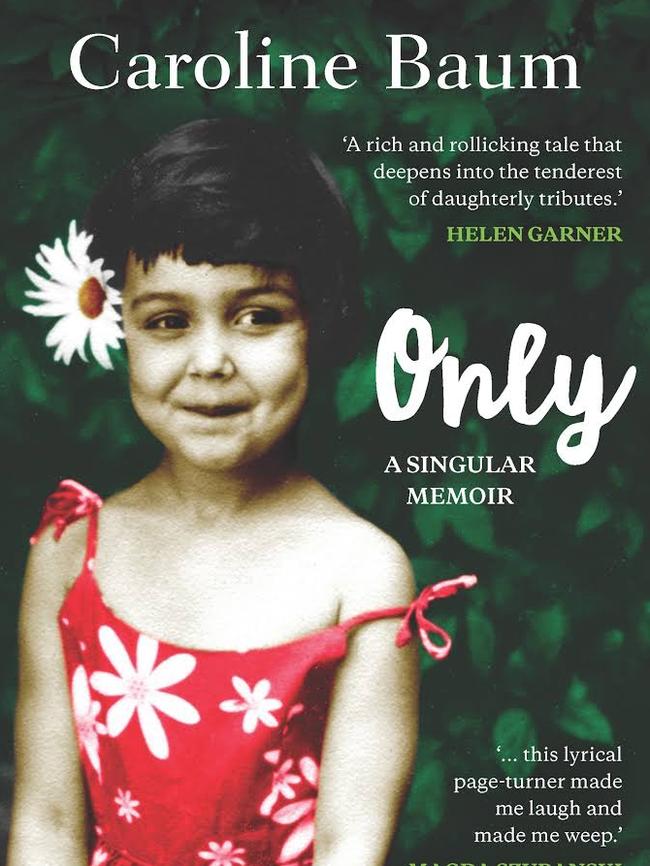

Caroline Baum’s memoir unveils her life as an only child

Caroline Baum’s memoir is an inquiry into being that single, precious child holding a family together.

Caroline Baum is the only child of displaced parents. Her father arrived in London at age 10 on one of the first kindertransport from Vienna in December 1938. Her French, not Jewish, mother was orphaned at five by a horrifying family tragedy. Caroline was born in 1958 in London, where her parents had settled to construct a life together in neutral territory.

Baum, an arts journalist and television presenter who now lives and works in Australia, grew up in a large, unwelcoming house in the London suburb of Wimbledon. Her father wanted to be an English gent, her mother wanted to be happy. Neither knew how to go about it.

These two intelligent people bought the trappings of Englishness and presented a public face of coupledom, but behind the facade they lived fractured lives. Only Caroline and a small dog fostered any closeness. Caroline saw her parents together in bed just once — they were comforting each other when the dog died.

Only: A Singular Memoir intends, perhaps, to be an inquiry into being that single, precious child holding a family together. Single children are Anita Brookner’s great subject and her background has remarkable similarity to Baum’s, but unlike Brookner, Baum hasn’t turned her life into fiction. Baum prefers anecdote to inquiry.

Yearning for authenticity, Caroline’s parents wanted to make their daughter into the perfect English girl. She was lavished with material things but in return her parents expected not love in the knockabout, gritty way most of us expect within family but a performance. Perhaps real emotions were too dangerous. They required adult behaviour and approval from the world.

Life clipped along a surface, and reflection or interiority were unknown. In the brisk Baum household, they all just got on with it. It being life. Little wonder that the child, with her lacquered self-confidence and drilled in adult behaviour, didn’t like other children.

Here is that child at play:

I devised new ways to torment our good-humoured, gap-toothed cockney housekeeper, Mrs Barns. My favourite tricks were to switch off the power point for the vacuum cleaner or floor polisher while she was rooms away or creep up behind her and tie her apron strings to the door ... she chuckled at this mischief though I was a proper pest.

At Christmas Mrs Barns gives the family “hideous gifts which we were obliged to display”, and Mrs Baum carries a notebook and pencil in her jacket, noting down Mrs Barns’s “hilarious” malapropisms while “trying to keep a straight face”. Then Mrs Barns retired and Mrs Baum “made several efforts to stay in touch, all of which were met with silence. It was puzzling and hurtful. Her big-hearted loyalty was missed and mourned.”

Where emotions were concerned, the Baums required an interpreter. The mantra of getting on doesn’t seem to have allowed space for emotional refinement in young Caroline’s education. Mrs Baum decided the “right” friends for her adolescent daughter and at 10 Caroline used to hope her bullying father would not come up to kiss her goodnight. His hugs were suffocating. Later, geographically stranded on the other side of the world while their daughter was beginning a new career, these selfish and childish people would become their daughter’s reluctant responsibility. There were long and guilty gaps in the relationship on both sides.

Brookner’s most autobiographical novel, A Start in Life, is narrated by a woman called Ruth Weiss who has the total responsibility for her two selfish and childish parents. But Ruth had the luck of a grandmother, a refugee from 1930s Berlin who gave her the fundamentals of good behaviour, the talent to get over herself. Ruth, always self-aware, is clear about the awfulness of her parents but equally clear about her responsibility.

Caroline, who had to make her way alone through the subtleties and terrors of human interchange, was understandably baffled and furious. But she did shoulder the responsibility of her parents, and the last part of this memoir has depth and interest as she recounts her despair at being the child they called on.

The first half has more shopworn anecdotes about bad haircuts, shopping expeditions and general awkward adolescence. The oddest chapter is about why she failed to get into Oxford. I experienced fremdscham most keenly at this point.

Caroline Baum is always ready to take on the world. She has no self-pity and it is heroic of a memoirist not to care whether she comes across as likable. Baum, who may have had in mind EM Forster’s approach to writing — “How do I know what I think until I see what I’ve written?” — seems oblivious of all the tiny revelations dislodged and trailing as she clips along the surface, anecdote after anecdote, dropping a few celebrity names who passed through her life, detailing endless trivia.

The co-dedicatees to Only are Baum’s husband, David, and her mother. She writes of her own marriage as sustaining, a radiant achievement given her background. Her energy is unfailing, and it emerges repeatedly in this recounting of a life that has not been smooth despite her parents’ well-intentioned but misguided efforts.

For those interested in single children, Only may be useful because childhood is the curriculum for life. Baum concludes that she has after all been a “good daughter”. She has her mother’s word for it.

Helen Elliott is a writer and critic.

Only: A Singular Memoir

By Caroline Baum

Allen & Unwin, 372pp, $32.99