Cannibalism: Bill Schutt explores the myths, tall tales and reality

Anthropophagy has long fascinated and appalled humans. Now a US professor hopes to separate fact from fiction.

Bill Schutt has an excellent subject, and he explores it from a promising angle. Cannibalism has long interested zoologists, anthropologists, historians, criminologists, literary theorists and students of theology and blasphemy (the absurd claim that Roman Catholics were commending it in their account of transubstantiation was a favourite with 18th-century English blasphemers).

Few people have tried to bring all these together, and perhaps by the end we have to conclude there is not much connecting the very different elements at the remote ends of the scale. Still, it was worth a try.

Schutt is a professor of biology at Long Island University. An animal scientist, he begins with the simpler organisms. At the bottom of the scale, cannibalism in invertebrates is quite common for particular purposes.

There are mother spiders that present themselves to their young to be eaten once their purpose has been served. In snails it is a passing phase: under a certain age, snails will eat their own eggs and lettuce indiscriminately, before eating only plants.

The freshwater fish cichlids breed their young in their mouths, and often eat a good proportion of them. They need to strike a balance. Fish can produce a huge number of eggs — up to 300 million in some species — which ought to make it possible to be generous in expenditure and to eat some of these high-protein emissions. If the fish eats too many, however — more than 80 per cent, for instance — then it seems to make more sense to eat the rest rather than devote energy to bringing up the few that remain.

Different sorts of cannibalism are recorded among animals. The eating of young — filial cannibalism — goes alongside sibling cannibalism, or the eating of rivals. This is memorably described in Ted Hughes’s poem about the pike, with its mysterious reduction of the number of pike in a tank, until suddenly there is only one, ‘‘with a sag belly and the grin it was born with’’.

There is heterocannibalism: eating others or others’ young. Whether polar bears have recently taken to doing this — perhaps an occasional practice has become more common because of global warming — is a matter of fierce debate.

Even with animal cannibalism, myths and cultural projections have to be disentangled. Sexual cannibalism, in which the female eats the male in the act of copulation, is rare, and in some species to which it is ascribed, hardly documented. It does happen with redback spiders. Why does the male have anything to do with a practice that will end with his death?

The Darwinian theory is that cannibalised redbacks copulate for longer and transfer more sperm, so the male will increase his chances of breeding by allowing himself to be eaten. Since the female spider who has recently eaten a male is less susceptible to the approaches of other males set on the same ambition, the eaten spider will also have beaten off his rivals.

Why some male spiders chase and eat females in the act of copulation, however — a practice that has gained much less publicity — is still puzzling zoologists. Perhaps the more interesting subject is why we place so much emphasis on the real or supposed practices of female insects that devour the males in the act of mating.

When we turn to human cannibalism, a sharp difference is immediately apparent: between widespread cultural practice and psychopathic behaviour outside society’s order. Neanderthals were said by HG Wells to eat each other (on flimsy evidence) and in The Time Machine he foresaw a revival of this in the remote future.

Much about the celebrated cases of early human anthropophagy turns out to be debatable. Conclusive evidence that cannibalism was practised would need proof that the fossilised coprolites that have been found containing human remains were also produced by humans, or that the cut marks that have been discovered on human bones were those of butchery and not of battle. It seems likely but not conclusively proved.

The early humans that preceded the Neanderthals, fading out about 150,000BC (known as Homo antecessor), do seem to have been cannibals, given the evidence of bones that have been cracked open to extract marrow.

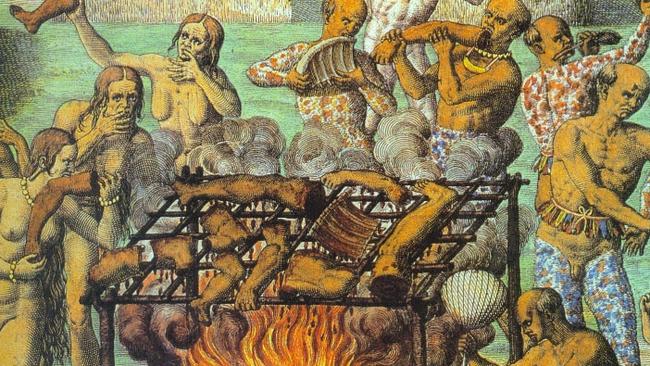

Since then, for the most part, the accusation of cannibalism has been directed at the Other. Anthropologists have often heard from tribal people that the practice of cannibalism is in full spate among the dreadful hordes that live beyond the mountains. On crossing the mountains, they have heard the same about the people they just left.

This has had its political uses. Early explorers in the New World, such as Columbus, were quick to ascribe cannibalism to the natives. In 1503 Queen Isabella decreed that natives who did not practise cannibalism should be freed from slavery — suggesting a belief in the custom being widespread. Usefully, the innocent indigenous Trinidadians were declared to be bestial cannibals so they could be subjected by the Spaniards.

During the larger part of the history of anthropology, academics have nevertheless accepted there are cultures in which dead humans are eaten: either the bodies of defeated enemies or the honoured remains of community elders. The evidence for this was quite limited, and largely restricted to oral testimony.

In 1979 the anthropologist William Arens argued there was no evidence that anthropophagy had ever occurred as a regular practice beyond second or third-hand accounts. (‘‘No ceremonial devouring of human flesh?’’ a disappointed anthropologist inquires at a seminar in one of Barbara Pym’s novels.) Arens was attacked at the time, but it seems clear that many accounts of cannibalism, even in modern times, are questionable. The best evidence for it has been the outbreak of kuru among the Fore people of Papua New Guinea — a fatal disease that appears to have been spread by their ritual habit of eating their elders’ brains.

Most of the indubitable cases of cannibalism have occurred in desperate and unique circumstances: among individual psychopaths, people in survival situations such as shipwrecked sailors and the air crash casualties in the Andes. There were many stories of cannibalism during the siege of Leningrad in World War II, and it has since emerged that 2000 people were arrested for the crime.

The most historically important case of cannibalism is one of the founding cases of English criminal law, Dudley and Stephens, which concerns a case of two sailors killing and eating a cabin boy. Surprisingly, it’s not mentioned by Schutt, despite its significance.

Perhaps more controversially, the author suggests the relative prevalence of incidents of cannibalism during Mao Zedong’s famines comes from the lack of dietary taboos possessed by the Chinese; but it is clear they do in reality see the difference between eating a snake and eating a child.

Schutt tries to draw his subject together by saying: “Cannibalism occurs across the entire animal kingdom, albeit more frequently in some groups than others.’’ This neglects the fact that as animals become more advanced, they are less likely to commit cannibalism. Snails routinely do so, orang-utans never.

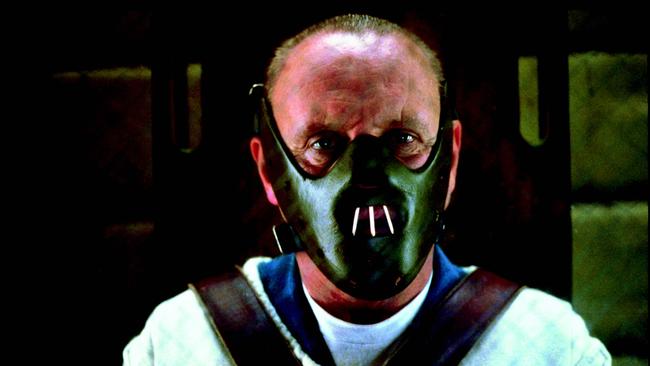

The most conspicuous place of cannibalism in human culture is, of course, in the grotesque fantasies of literature. Cannibals can be found in Homer; through the folk tales recorded by Grimm; and onwards to contemporary villains such as Hannibal Lecter. In this context it does not matter that such acts hardly ever happen, and it’s tempting to suggest that literary fantasies about cannibals created real-life psychopaths such as Jeffrey Dahmer.

The greatest work of literature about cannibalism is Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal, which isalso not mentioned by Schutt. It’s worth noting, however, that the irony of the great pamphlet only works if we accept that cannibalism will never become an accepted part of human society.

This is an interesting book, which inevitably contains a lot of fascinating stories, but its bold attempt to trace a line between the routine habits of simple organisms and the periodic surfacing of anthropophagy cannot, thank goodness, be sustained.

Philip Hensher is a novelist and critic.

Eat Me: A Natural and Unnatural History of Cannibalism

By Bill Schutt

Profile, 256pp, $32.99 (HB)