British Museum in safe hands but should the Elgin Marbles go home?

In his first interview since taking charge of the crisis-hit institution, Mark Jones talks about exhibiting the jewels that disappeared from its vaults, accepting BP’s millions — and the future of the Elgin Marbles

The great thing about being hauled out of retirement to rescue a floundering institution is that you don’t have to pretend things are better than they are. “How are you enjoying being back at the British Museum?” I ask Mark Jones, who was summoned last September, at age 72, to take temporary charge of an organisation enduring an annus horribilis unprecedented in its 271-year history.

“Some days are terrible, others not too bad,” he replies with an expression fixed somewhere between a Roman martyr and a Greek stoic. He has had a marvellous career, starting as a BM curator in 1974 then running the National Museums of Scotland, followed by 10 years at the helm of the V&A and six years as master of an Oxford college. So what on earth persuaded him to respond when George Osborne, the BM’s chairman, begged him to come and steady the ship in Bloomsbury after the unhappy departure last August of its director, Hartwig Fischer?

“Curiosity, I suppose,” he replies. “I didn’t say yes straight away. Then I thought: ‘This is madness, but I might regret it if I looked back and wondered whether there was anything useful I could have done’. ”

Most observers would say he’s already been much more than useful. For a start, he has calmed the media storm over the revelation about 2000 missing items, which the museum believes were stolen from a single, uncatalogued collection in the BM over several years, despite warnings from an outside expert that were ignored. The items included gems and semiprecious stones set in rings – some ancient (including some Bronze Age earrings) but many others relatively modern imitations. More than 350 have been recovered with another 300 identified, and the BM is hopeful of recovering the vast majority of the rest.

“Dealing with the consequences of the theft was obviously my first priority,” Jones says. “What made the theft possible was that many of the stolen objects were effectively unknown to scholars. They weren’t properly recorded, they weren’t on our databases.”

So Jones has set a target of five years for the BM’s complete collection – all eight million objects – to be catalogued online, each with an image. What’s more, the entire digitalisation is to be accomplished without public funding. “We’ve raised more than half a million towards it already,” he says. “And about 60 per cent of our collections are digitally recorded already.”

But that’s just one of Jones’s remedial actions. When he and Osborne were summoned to explain the alleged thefts by a Commons select committee, they spoke about the need to change the “trusting culture” among the BM’s staff. Necessary, maybe, but isn’t it also rather sad? “It’s very difficult, isn’t it?” Jones replies. “You need to trust your colleagues, yet you also need to be aware that thefts by people working in museums aren’t as rare as you would hope. In fact there have been thefts at the BM going back to at least 1806.” One upshot of this belated reality check is that nobody, not even the most senior and “trusted” of curators, is now allowed solo access to strongrooms – something that was possible at the time the items went missing.

At least one sliver of silver lining has emerged from this dark cloud. Ten of the recovered stolen items will be featured in a new BM exhibition called Rediscovering Gems, opening on February 15. “Until last year it might have been hard to get public interest in a display of engraved gems,” Jones says. “But the truth is that these are stunning objects with a fascinating history.”

Part of the fascination, it transpires, is that the gems were themselves fakes of classical jewellery – ironic given how much deception has been involved in their recent history. “It partly explains why they were originally considered unworthy of being registered in the BM’s collection and therefore vulnerable to theft,” Jones notes.

Doesn’t all this talk about theft lead naturally to the clamour for the BM to give back the many contested items in its collection? “Really? I’m not sure about that,” Jones says sharply. Well, Australian Geoffrey Robertson, one of the world’s leading human rights lawyers, did once declare that the BM’s trustees are “the world’s largest receivers of stolen property”.

Jones bristles at such a broadbrush accusation. “That, if I may say so, is complete nonsense,” he replies. “The vast majority of what we have are legitimate archaeological finds or have been traded legitimately. The idea that everything in the BM somehow has a reprehensible past is completely untrue.”

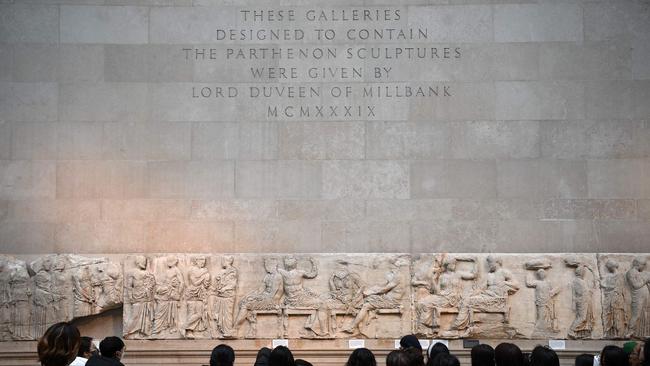

Fair enough, but isn’t Jones on board with Osborne’s declared aim of trying to negotiate an agreement with Greece over the most famous of those contested items – the Elgin Marbles (or Parthenon sculptures, as the BM scrupulously calls them)? And doesn’t the deal announced last month, whereby the BM and the V&A will make a long-term loan to Ghana of some of the Asante gold looted by British troops in 1874, suggest a template for how awkward questions of restitution can be resolved in future?

“It’s true that I find the legal situation of contested objects, and the historical justification for retaining them, much less interesting than consideration of their current and future benefits,” Jones says. “What we should really be thinking about is where these objects are going to create the most interest, where they are best going to engage people.”

Perhaps, yet there’s a frequently heard argument that long-term loans of contested material will “open the floodgates”, leading to existential questions about whether “world museums” such as the BM should exist at all. “There’s a tendency in human affairs to make a very rapid flip from one state of mind to its polar opposite,” Jones says. “So yes, there is a danger with museums that we could quickly flip from the attitude of ‘nothing must go’ to ‘everything must go’. But that’s why it’s important to make arrangements with people around the world that show the benefits of sharing objects – of making contested items the subjects of mutual collaboration rather than causes of hostility.”

So could Jones envisage supervising an arrangement to return the Elgin Marbles to Greece? “Yes,” he replies. “I could easily imagine a relationship between us and the Acropolis Museum (in Athens) that included mutual loans. Why not? They have some rather fabulous objects as well.”

Such sharing arrangements would fit Jones’s vision of the BM’s future as a vital source of scholarship, expertise and fascinating objects for the whole world, not just the five million people each year who access these things in Bloomsbury. “Our work around the globe gets a lot less coverage than it should,” he declares, and he reels off a list of projects to prove it – excavations of the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu in Iraq and of Benin City in Nigeria; a collaboration on a groundbreaking exhibition in Mumbai of 2000-year-old sculptures from several different civilisations; and a touring show on the Ancient Greeks that’s attracting huge crowds in China. “That’s been seen by 2.4 million people,” he says. “It’s a reminder that a lot more people see the BM’s stuff outside the BM than inside.”

The biggest challenge facing the museum is revitalising its Bloomsbury site. The latest exhibition, Legion, has drawn rave reviews. But the general collection is housed in a 200-year-old site, with all the leaky roof and crumbling infrastructure problems of old buildings everywhere, plus dated gallery layouts and acute overcrowding in the summer months, especially around its most popular exhibits such as the Rosetta stone.

An ambitious masterplan of renovation and renewal expected to cost well in excess of £3 billion ($A2.5 billion) was devised a decade ago.

The most exciting and public aspect of the masterplan – the project to rethink completely the galleries known as the Western Range, including the rooms housing the famous antiquities from Egypt, Greece and Rome – hasn’t been started. It’s to get that under way, initially with an architectural competition, that the BM’s trustees decided in December (after months of “wrestling with the decision”, according to Jones) to accept a $A120 million donation from BP, the oil giant now shunned by almost every cultural organisation that once accepted its sponsorship.

Presumably Jones agrees with the trustees? “Nobody’s pretending it’s not a difficult decision, but it’s the right one. To turn down that very major act of generosity would imperil our chances of doing work that is badly needed. I don’t think it’s a sign of a serious attitude to complain about a lack of funding and then reject funding offered from perfectly respectable sources.”

But won’t accepting BP’s money imperil the museum in other ways? Already an environmental lobby group called Architects Declare has called on architects to boycott the masterplan competition. Soon, no doubt, other activists will be mounting disruptive protests inside the museum, as they have done before. Their argument, of course, is that BP is far from a “perfectly respectable” source of funding.

“If one is serious about dealing with climate change, as I certainly am, we have to recognise that it involves a transition,” Jones replies. “Oil giants like BP, which do derive their main revenue from fossil fuels, are also major agents of transition to the new technologies we need. If you look at BP’s investment, you see a major part of it now goes into green technologies. Why wouldn’t it? What is the future of such companies if not to transition?”

The BM’s board has to make one other crucial decision: to select a new permanent director. Will Jones’s last gift to the museum be to help the trustees choose the right person? “No, I’m not going to take any responsibility for that,” he says – and actually smiles for the first time in our interview. “Nobody should take part in the selection of their successor. It’s just too tempting to look for someone a bit like yourself, but not quite as good.”