Brian Cox: acting on instinct

Constantly catching the audience off-guard’ is how Brian Cox, star of Foxtel hit Succession, has worked his craft over six decades.

Fans have been treating Brian Cox a little differently of late. It all started when the Scottish actor was appearing in a play in New York, the city he’s called home for almost 15 years. “I was playing Lyndon Johnson,” he says over a video call, lounging on a sofa in the London pied-à-terre where he’s spent most of the year, to be close to family. “Somewhat vertically challenged I am, to play Lyndon Johnson … but I was playing him.”

And it was at this point, a couple of years ago, that punters at the stage-door started asking for more than just his signature. “Young lassies with their boyfriends” started coming around, says Cox, and with a very specific request. The 75-year-old here adopts a prim, feminine, American voice. “Can we have a video?” he trills. “And can you please tell us to f--k off?”

Those two little words are something of a catchphrase for Logan Roy, the media mogul played by Cox on the HBO series Succession, which returns on October 18 after a two-year, pandemic-affected break. And though the actor himself seems a little nonplussed by the question – “it is a request I get regularly,” he deadpans – demand is unlikely to dissipate any time soon. Such is the popularity of the show, which is now entering its third season and has replaced Game of Thrones, another tale of dynastic gamesmanship, as the cable behemoth’s flagship drama. Succession has also gifted Cox what could prove to be his most iconic role, even after a long and storied career spanning six decades. Inscrutable and ruthless, Logan is nothing like the man who plays him. But the role is undeniably patterned on Cox, too.

The degree to which that’s the case has surprised even the actor himself. In fact, he spent most of the first season thinking his character was Canadian until the show’s creator, Jesse Armstrong, informed him that Logan was actually from Dundee, Cox’s hometown. “He said, ‘Oh, we thought it’d be a little surprise’. I said, ‘A surprise!? I’ve just spent a whole season playing this other guy’!” Armstrong assured him that Logan had been sent to Quebec as a child, at the outbreak of the Second World War. And anyway, the murkiness of the character’s past is part of his legend. Logan is a self-made man whose scornful attitude to his gormless American children arises from the fact they’ve had it easy, even if that’s a product of his own success.

That tension is, of course, irreconcilable, and therefore the perfect grist for an ongoing series. Cox, for his part, ascribes Logan’s harshness to a hard-scrabble childhood not entirely dissimilar to his own. The actor’s father, who worked in the local jute mill before opening a grocer’s shop, died of cancer when his son was just eight years old. In the aftermath, Cox’s mother had a series of nervous breakdowns, unable to cope with the debts her open-handed husband left behind. She eventually received electroshock treatment, and Cox was raised partly by his older sisters.

Later, in school, the boy was introduced to acting by teachers who put him in touch with the Dundee Rep, where he worked as a stagehand and then stage manager. A few years later, when he was still a teenager, Cox won a grant to study at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, just as working-class lads such as Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay were emerging as stars. “The 60s for me was the greatest time of social mobility,” he says. “London always means that to me. It was my taste of freedom. I felt welcomed here. It’s all changed, of course.” It was a time, he says, of shaking things up. The training he received was, at the same time, very much a classical one, in the tradition of the British theatre. And it’s one for which Cox is grateful.

“I really can’t deny what it gave to me,” he says. “A lot of other stuff was s--t, you know – the feudal thing in this country drives me buggy. But the craft, the work … you know, as a young actor I was able to watch Paul Scofield rehearse. Playing Uncle Vanya. And I’ve never seen anything like it.”

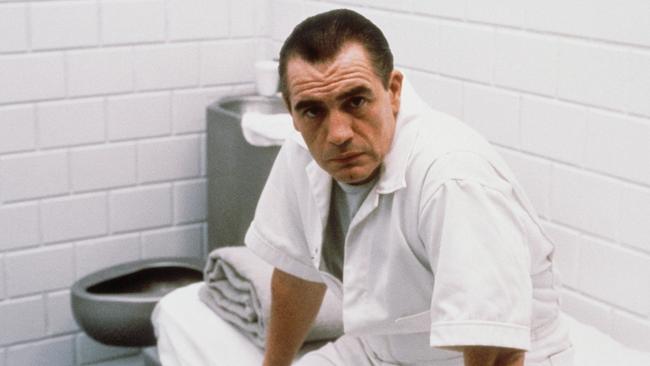

Cox worked regularly in British television over the next two decades, but it wasn’t until he performed on the New York stage that he cracked Hollywood. A casting director in the audience recommended him to filmmaker Michael Mann, who was looking for an actor to play a dapper forensic psychiatrist turned killer in his 1986 thriller Manhunter. Years before Anthony Hopkins won an Oscar for the same role (in The Silence of the Lambs), Cox imbued the part with the jowly menace that has remained his signature ever since, in everything from Braveheart to The Bourne Identity. The actor’s specialty is a certain gimlet-eyed impatience, and his line readings land like cracks of the whip.

Like Logan, Cox now has American sons – two teenagers with his wife, the actor Nicole Ansari – as well as an adult son and daughter from an earlier marriage to actor Caroline Burt. His oldest kids even went to English public schools (“my first wife’s decision, nothing to do with me”). And he’s aware he was slightly absent – too busy working, developing his career – the first time around. That’s one thing, he says, he understands about Logan. Another is a certain disappointment in humanity. “He sees through so much that it’s made him quite a lonely and quite a cynical figure. I’m the opposite. I’m quite optimistic. I don’t have that cynicism. But I do share the disappointment.”

What exactly is he disappointed about? “What’s been going on with cancel culture and the woke thing. I can’t be doing with any of it, really. I think it’s mindless and hypocritical. Now, I think Logan’s never really had any respect for his fellow human beings. Because of the bitterness that is really at his core. And I haven’t got that bitterness. But I understand where that … can come from.”

From Logan’s traumatic childhood? That’s right, says Cox. Poverty and displacement are things about which the actor knows, and those early experiences have clearly shaped not only the man but his approach to the work. Cox occasionally teaches acting, and he always tells his students to carry a picture of themselves as children. To remind them, he says, who they really are. “There’s something about children – an openness, you know, a sense of wonder – that gets traduced and violated, in a way, by experience.”

There’s a distinct theatricality to Succession, which is shot handheld and has plenty of long, talky scenes in boardrooms, penthouse apartments and yachts. The show began with Logan’s children jockeying for position after their father suffered a stroke. And the jockeying never really ended, even after the tycoon regained his health. This premise has seen the show compared to Shakespeare, and especially to King Lear. The difference, of course, is that Logan holds all the cards and never relinquished power. The series never tries to sentimentalise his “damage” or offset his unpleasantness by showing his softer side. He’s an unknowable figure to the last.

That’s something Cox has been careful to maintain. “I do have scenes where I go very near the knuckle,” he says, “where you reveal this mania that he has. And I just said, ‘we have to keep that in check. That mustn’t be allowed’.” One of the actor’s precepts, in fact, is to never let the bastards know what you’re thinking. “It’s very important to maintain your secrecy, maintain your mystery. So that you’re constantly catching the audience off-guard, in the right way. Because human beings are fascinating. They’re not always what they appear to be.” And that’s especially crucial, he says, when one is developing a character over a long period of time. “That impenetrable thing has to remain. Because that’s what’s human, you know? It’s a mystery.”

By way of example, Cox recalls a strange convergence of events which took place just the week before our chat. He was about to visit his sister when he received a call from his Camden tenants (his property portfolio also includes a house in upstate New York, in addition to the apartments in London and Manhattan). They’d found a battered old bag containing some papers, and forwarded it on. Inside were several hand-written pages scribbled by his mother in the wake of his father’s death, and he took them with him when he went to see his sister, who is now 91 years old, in her nursing home.

“And I read this thing to her, and she was very touched by it. She was also very impressed by my mother’s articulacy. She said, ‘Ma was always very smart’. And I’d never heard that before. I never heard her talk about Mum in that way. Because they’re great, my sisters, but they can be quite critical of their parents.”

Cox was bowled over by the whole thing, not least because he’ll shortly be returning home to the States. “And you know, my sister … she’s a certain age. So I don’t know how often I’m going to be seeing her, over the next …” He trails off. Though he doesn’t believe in God, there was something extraordinary, he says – not to mention mysterious – about the timing of it all. A certain cosmic rightness. “And that’s what Jesse catches brilliantly, I think, in the writing of the show. The clash of circumstances. And that’s what keeps it real and true.”

Serendipity also helps explain how Succession became the show of the moment. Cast and crew wrapped the pilot on the day that Trump was elected. And when the show finally premiered, two years later, it seemed almost to be riffing on the First Family. Unsurprisingly, Cox – who describes living in America as “truly horrific” under Trump – doesn’t discern much of a likeness. “I don’t think Logan would have liked Trump at all. Because Trump represents naked avarice. Logan isn’t about naked avarice at all.”

Another name that has been invoked in coverage of the show is Rupert Murdoch, owner of NewsCorp, publisher of The Australian. Though the endless speculation about who Logan is modelled upon seems pointless — he’s a composite figure, according to Armstrong. There’s a certain mystery to the Australian, however, says Cox. “He really has influenced things. But you can’t deny it. You can’t deny his … what’s the word? His rigour. His own particular rigorousness.”

Succession’s second season finale promised a generational clash. And the universal nature of that collision perhaps explains why viewers might identify with characters who, as Cox admits, are both obscenely wealthy and frequently vile.

“The risk was always that you alienate people – ‘I don’t know if I want to be spending any time with these people’,” he says. “But then you realise they are human beings. And they are flawed. They’re deeply flawed, as a lot of us are …” He chuckles. “Some more than others.”

Succession Season 3 premieres Monday, October 18 on Foxtel.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout