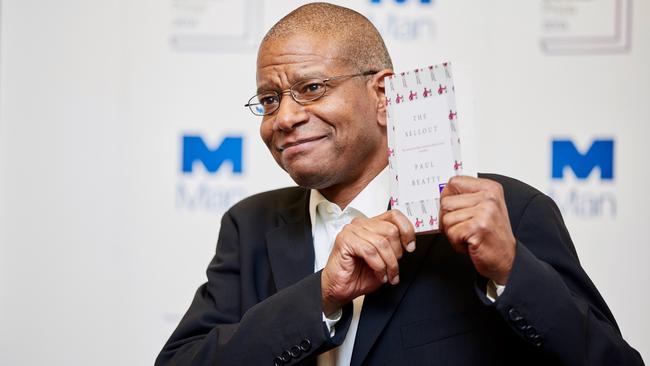

Booker winner Paul Beatty on race, political correctness and Huck Finn

Political incorrectness is Man Booker Prize winner Paul Beatty’s stock-in-trade but he’s making no apologies.

“This may be hard to believe, coming from a black man, but I’ve never stolen anything.” That is the provocative opening line of Paul Beatty’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel, The Sellout. The same mocking tone, dry as sun-bleached bones, pervades this satire by Beatty, the first American to win the Man Booker, literature’s highest-profile award.

Variously described as “badass”, “outrageous” and a “work of genius”, The Sellout centres on a pot-smoking African-American farmer who is hauled in front of the US Supreme Court for taking on an absurdly willing black slave and seeking to reinstate segregation in his home town — an agrarian ghetto in southern Los Angeles, symbolically named Dickens.

A 21st-century slavery and segregation campaign championed by black Americans? Is this an all-or-nothing literary gamble? You bet. Is it edgy? Beatty, who seems to drop the N-word on every other page, might have invented the term.

A former poet with an aversion to the phrase “spoken-word poetry”, Beatty pokes fun at everything from the civil rights movement to the lack of Korean taco trucks in non-white LA neighbourhoods.

“They won’t admit it, but every black person thinks they’re better than every other black person,” says The Sellout’s slave-owning narrator, named Me. Meanwhile, a perennially indignant black activist, Foy Cheshire, is lampooned for attempting to rehabilitate the classics with titles such as Uncle Tom’s Condoand The Great Blacksby.

White people are also in Beatty’s sights — along with the insidious myth that, having had a “black dude” in the White House, the US is an equitable, post-racial society. In a chapter titled Too Many Mexicans, Beatty’s narrator says different ethnic groups in California have long uttered this racist lament, among them middle-class whites: “The type who never used to have anything to say to black people except ‘we have no vacancies’ and ‘you missed a spot’ … finally have something to say to us.”

The Guardian called The Sellout “the most lacerating satire in years”, while US comedian Sarah Silverman has said “demented angels” might have written it.

Yet Beatty the interview subject turns out to be as circumspect as Beatty the writer is uninhibited. As his rich baritone notes surge down the line from his New York home, the 54-year-old writer is obliging, friendly — and stubbornly understated. On the bigger issues his novel excavates, such as the unofficial racial segregation of US schools, he is positively noncommittal. His message seems to be that he is nobody’s messenger.

The author — who will speak in Brisbane tomorrow and is headlining this week’s Sydney Writers Festival, with one of his sessions already sold out — says: “I think that people are smart enough, you know, to hopefully just enjoy the story.”

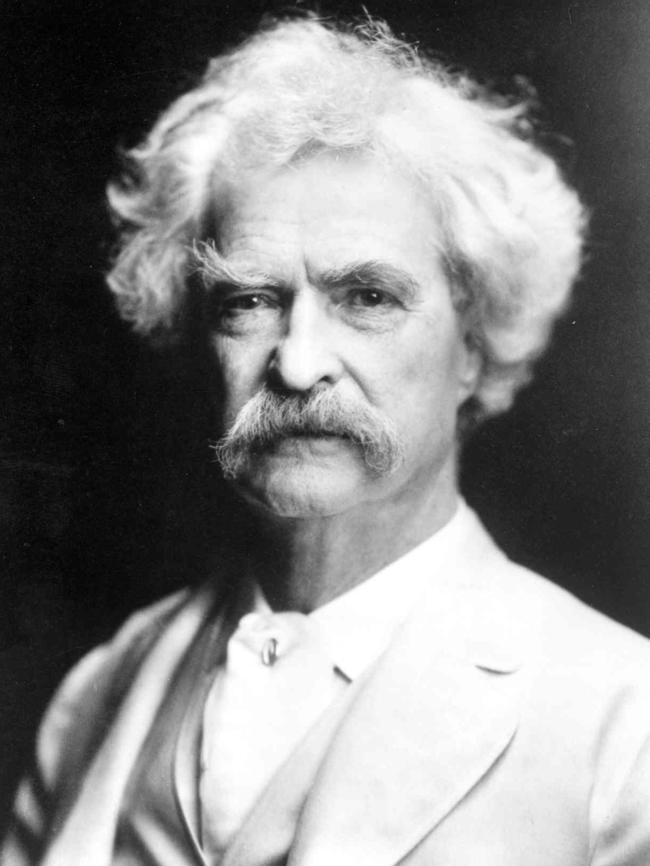

The reticent literary star even considers the word “satire” problematic: “I don’t think the book is satire, really. It might be funny, but I’m not writing the book to provoke a response.” Earlier this year, he said on an NBC talk show that the satire label created a burden of expectation: “That label comes with a big burden, you know, the Mark Twain kinda [thing]. You have to be witty, you gotta wear a seersucker suit all the time.”

So where did this audacious idea come from — an African American who, albeit reluctantly, takes on a black slave and decides to put his crime and poverty-blighted town (even Chernobyl refuses to be twinned with it) back on the map by segregating a local school? Beatty, who grew up in Los Angeles, says his novel began with an idea for Hominy the slave — an 80-something “race reactionary” and former child actor who begs to be enslaved after Me talks him out of committing suicide. Hominy believes a segregated school will “make Dickens more attractive to white resettlement”.

“I just kind of built that world around that character,” says Beatty. “It was a good way not so much to bring the past and future together but just to talk about a lot of things in a funny context.” He notes how his first novel, The White Boy Shuffle, features a minor character “who runs away into slavery. He’s a dancer and he loves the way they move as they pick the cotton.”

Given his habit of turning historical traumas on their heads for comic effect, he says that “after every book I write, somebody asks me the question — ‘Is X, Y and Z mad at you?’ Not that I’ve heard. The books are more than just trying to take the piss out of a certain section [of society].”

Despite trafficking in politically incorrect gags, Beatty has said The Sellout is “a sad” book. Asked about this, he riffs casually: “I don’t know why I said that. I say something different about the book every time somebody asks me.”

Last October, the sometime contrarian made history by becoming the first American to win the Man Booker Prize. His latest novel had already garnered America’s prestigious National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction — past winners include Hilary Mantel, Junot Diaz and John Updike. (In 2014, the Booker — previously limited to British, Commonwealth, Irish and Zimbabwean writers — was expanded to include all novels written in English, provided they had been published in Britain.)

Beatty says he was surprised to take out the Booker, and footage of the ceremony shows a tall, bespectacled man, suited up and kind of mortified as he is overcome with emotion. He said: “I can’t tell you guys how long a journey this has been for me … I don’t want to get all dramatic — writing saved my life or anything like that.” Then he choked out something exactly along those lines: “Writing’s given me a life.” Since he won the prize, the writer says his existence has been “a little bit” of a whirlwind. “You do a bit of travelling and lots of talking,” he says, chuckling. Interestingly, despite earning rave reviews, The Sellout struggled to find a British publisher after its successful US release. It was turned down by 18 British publishers before small, independent publishing house Oneworld took it on — the same company that published Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, the previous Man Booker winner, in Britain.

Beatty downplays his novel’s bumpy trajectory towards British publication, which was interpreted as a sign of publishing’s conservatism. Nevertheless, he wonders whether “there’s this niche of what a story’s supposed to read like. I meet editors every now and then who see books that they like, but they really can’t acquire because they don’t think they’ll be able to sell it.”

He reveals he recently judged a literary competition — he won’t say which one — and was struck by the “sameness” of the books in contention. “It didn’t matter where the book was set or what period the books were set in. I was just like, ‘These books are all the same, they’re structured the same, just all the same tone.’ And I realised they’re just kind of comfortable, even when dealing with uncomfortable [subjects].”

James, the 2015 Booker winner, has accused publishers of pandering to the tastes of white, middle-class female readers. Beatty is more diplomatic as he says: “I don’t think it’s the publishers who are pandering, it’s the writers who are pandering. I think people try to figure out an audience, and sometimes a lot of people write to an audience … Part of that has to do with a need to be liked, kind of writing to be liked in a weird way. I don’t write not to be liked, but I don’t write to be liked. I just try to trust what I’m doing.”

He has written four novels, all set in multicultural and black communities, and two books of poetry, and in 2006 he edited an anthology of African-American humour titled Hokum. In the introduction, he showed the same startling irreverence he brings to his fiction.

He wrote about reading canonical black writers as a young man and “welcoming the rhetoric but over time missing the black bon mot, the snap, the bag … It was as if the black writers I’d read didn’t have any friends.” He concluded: “The defining characteristic of the African-American writer is sobriety — unless it’s the black literature you buy from the book peddler standing on the corner next to the black-velvet-painting dealer, next to the burrito truck: then the prevailing theme is the menage a trois.”

His journey of literary insobriety shifts up several gears in The Sellout. The novel is replete with jokes that seem calculated to give offence, at a time people take offence all too easily. At one point, Me says: “Like most black males raised in Los Angeles, I’m bilingual only to the extent that I can sexually harass women of all ethnicities in their native languages.”

It eventually becomes clear, however, that Me and Hominy’s segregation mission is a case of these characters mocking their own powerlessness — can you segregate a school that is already devoid of white students? What is the point of reinstituting “whites only” seating on public buses when whites don’t ride on them? Me and Hominy’s separatist campaign in Dickens is absurd not just because it is offensive but because the town — inspired by the real-life Los Angeles district Compton — is already effectively segregated. When asked about this, Beatty (predictably) turns vague. “People know the plight of schools, they don’t need me to do it [comment],” he says, insisting he is just presenting “a story”.

The author teaches creative writing at New York’s Columbia University. Given the risks he takes with his fiction, does he find that universities, with their talk of safe spaces and micro-aggressions, are no longer places for dissent? “I never really hear anyone talk about what a ‘safe space’ really is in a concrete way,” he says. “I don’t kind of pay attention to it. I understand the need for students to feel not threatened. But then there’s the idea of what does being threatened mean? That’s one of the things that the book is about — we throw out all these words — safe space, segregation — and no one talks about what these things are.”

Even so, he notes how a colleague felt he couldn’t teach a poem because his students deemed it anti-Semitic. “I was like, ‘It is, but it’s still a powerful piece of literature.’ But he just felt like he couldn’t teach it. I didn’t judge him on that. I don’t know how I feel about these things, necessarily, to be honest. But I know they’re worth talking about. I think they’re worth fighting about. I tend to side with the people who I think are most vulnerable, but that doesn’t give you licence to do anything [in terms of censorship].”

Unlike his character Foy, who turns Twain’s Huckleberry Finn into a “politically respectful” work, replacing the word slave with “dark-skinned volunteer”, Beatty is “not a person who’s trying to erase the past, at least not in that way. I don’t get that. That book has been around for a long time, for a reason … I think some of the discomfort [with Twain’s use of the N-word] is the stuff that you gotta deal with. Sometimes there are things that make me deeply uncomfortable, but I’m really attracted to it. People have a hard time handling that kind of dissonance.”

Married, childless and intensely private, Beatty started his literary career as a poet. In 1990, he won the New York Grand Slam poetry championship, and this led to publication of his first book, the hip-hop influenced poetry collection Big Bank Take Little Bank.

He has performed his poetry on MTV and in the early 1990s he visited Berlin with other US poets who declared themselves “cutting-edge” and — even worse in his view — “spoken-word poets”. He told the Full Stop website: “I had never heard the phrase ‘spoken word’ before. I had no idea what that meant. I hoped that wasn’t what I was doing. I just really hated it. It sounds really politically correct — it’s gobbledygook.”

While he comes across as self-contained, he jokes that writers “are so needy — the talking is one thing; being around [them] is another thing”. He was raised by a single mother, a nurse who encouraged him and his two sisters to read Saul Bellow and Joseph Heller. Interestingly, Beatty revealed in his Full Stop interview that while growing up in LA, “I would go and visit my girlfriend at the time in junior high … [and] the cops would stop me and tell me, ‘You don’t belong here, get the f..k out’ … There were no [segregation] signs, but I learned there were definite signs there.”

After graduating from school, he left LA — described as “mind-numbingly racially segregated” in The Sellout — for New York and Boston, where he studied creative writing and psychology respectively. “Psychology is a big part of how I see the world and that, of course, influences at some level how I write or how I choose to render the world,” he says. His psychology background surfaces in his Booker winner, as Me’s father conducts bizarre experiments on his son, including electrocution and a public mugging, to teach him about the plight of black Americans. (Me’s father is eventually shot dead by the police.)

I ask Beatty whether he sees Hokum — and by extension his comic novels — as an antidote to the high seriousness that revered African-American writers brought to their work. Really, I should have known better.

“Absolutely not, it’s not an antidote to anything,” insists this author who has earned a place in the history books with his Booker win, yet refuses to make claims for his writing. “Any spaces I’m filling in are just spaces I’m filling in for myself, but for anybody else? I’m not trying to fill a void or anything.”

***

BEATTY’S BONS MOTS

From The Sellout:

“Apartheid united black South Africa, why couldn’t it do the same for Dickens?”

“They say ‘pimpin ain’t easy’. Well neither is slaveholdin’. Like children, dogs, dice and overpromising politicians, and apparently prostitutes, slaves don’t do what you tell them to do.” — Me, a black, 21st-century slave owner

“[California is] a police state that protects only rich white people and movie stars of all races, though I can’t think of any Asian-American ones.”

“The type [of white people] who never used to have anything to say to black people except ‘we have no vacancies’ … finally have something to say to us” — On the racist complaint there are “too many Mexicans” in California

“Like most black males raised in Los Angeles, I’m bilingual only to the extent that I can sexually harass women of all ethnicities in their native languages.” —Me

***

Paul Beatty will speak at the State Library of Queensland tomorrow and at the Sydney Writers Festival on May 26 and 27.