Bob Carr: ‘Of course opera is preposterous’

There was nothing in Bob Carr’s early 60s working class childhood to tilt him to an artform invented in the ducal court of Mantua in the 1600s - but he ended up falling in love with opera.

The fibro cottage on a sandhill in a new release area and the new glass and aluminium state school: there was nothing in my early 60s working class childhood to tilt me to an artform invented in the ducal court of Mantua in the 1600s. I remember two encounters with opera: a music teacher playing an aria from Mozart’s The Magic Flute; and a screening of Verdi’s Aida on black and white TV.

In my late 20s, browsing the black vinyls in Michael’s Music Room near Sydney Town Hall, I saw a box set of Lucia di Lammermoor sung with Joan Sutherland and Luciano Pavarotti, conducted by Richard Bonynge. It was time to give opera a chance. It was gripping, and instantly accessible, as much as the fare my parents liked – the songs from South Pacific or My Fair Lady.

Of course opera is preposterous. People singing their emotions, sometimes five characters belting out different emotions simultaneously. Bel canto vocal acrobatics can sound unearthly. Yet in the 19th century, opera houses spread like movie theatres in the 1920s and 30s. Melodies were broadcast by barrel organs and brass bands for people sitting in piazzas sipping coffee. Opera was popular entertainment.

Michael Foot, leader of the British Labour Party in the early 1980s, said he loved the operas of Donizetti and his peers because it had been the music adored by his literary and political heroes Keats and Shelley. Lincoln heard a performance of Donizetti’s comedy, Daughter of the Regiment, stuffed with American patriotic songs. A young Benjamin Disraeli, flamboyantly dressed and pining to be prime minister, would have attended Donizetti’s works snatched up by London theatres.

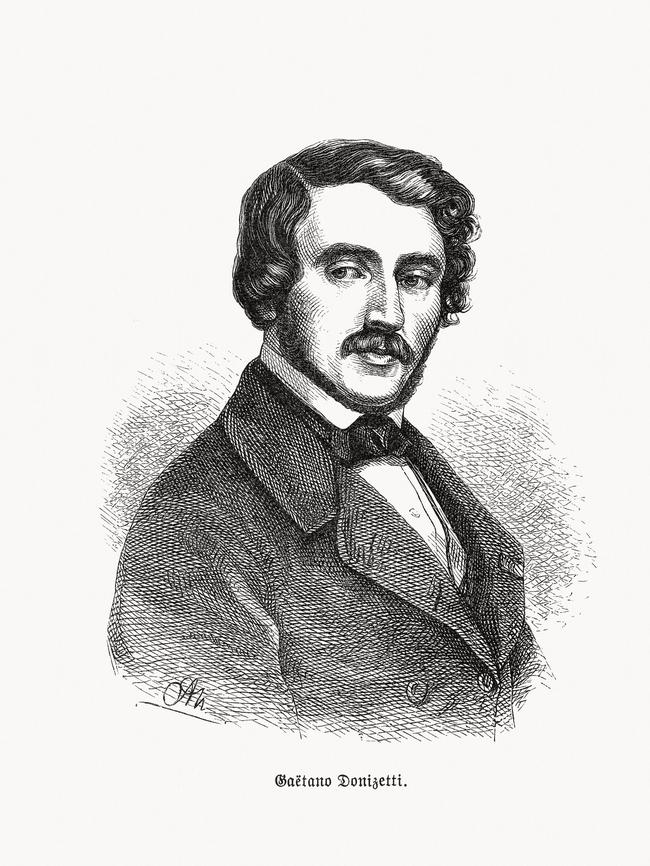

Born to a poor family in 1797 in Bergamo, northern Italy, Gaetano Donizetti had a career trajectory that propelled him from a local music school to the front rank of this surging globalised entertainment. Think of the international celebrity of Andrew Lloyd Webber. Except that Donizetti spun out 75 works compared to Lloyd Webber’s 21. And his music, grounded in Mozart and Beethoven, was burnished with spectacular vocal range and propulsive melody. Further up the food chain.

As I played and replayed the Bonynge-Sutherland recording – the only opera in my collection – I wondered whether Donizetti’s magic throbbed as powerfully through the rest of his works. This instinct might be called completism, like the idea of seeing all of Shakespeare’s plays, the full 39. If Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina and War and Peace are the greatest novels ever written, as they clearly are, that’s reason enough to dive into the 16 novellas.

If Lucia was so good, what of the other 74?

An annual Donizetti festival in Bergamo tests the thesis. Each year, as well as staging the most authoritative versions of his more famous works, it revives a Donizetti that was premiered 200 years ago but not staged – or rarely – since. Last year it was Chiara e Serafina, with a clumsy libretto delivered to the composer just weeks before the scheduled 1822 premier at La Scala. It flopped and was not revived till last year’s festival.

It’s a madcap comedy worthy of the Marx Brothers. But it hints at the 25-year-old’s emerging genius. Last year the festival also recruited internationally esteemed singers for the rarely performed early comedy The Tutor Embarrassed and of a mature tragedy, La favorite, that has enjoyed occasional performances in the big houses.

Riccardo Frizza, musical director of the festival, says: “No one is better writing operas about power struggles and family dynamics. With Tutor Embarrassed we see a father restricting the love life of a dominated son. And the drama that erupts from this. It’s about the struggles of the young and the big themes of love and betrayal.”

This year’s festival in November and December, will indulge the “completist” notion by staging Alfredo il Grande (Alfred the Great) and Il diluvio universal (The great flood) both lost to memory. Not even a season ticket holder to the Vienna Staatsoper, Covent Garden or the New York Met will have seen these products of Donizetti’s galley years.

Bergamo (population 900,000) has an upper town reached by a funicular with cobblestone streets and neo-classical facades, the hometown Donizetti kept returning to. There’s an intimate piazza and ensemble of medieval churches. The Accademia Carrara holds a collection of Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque art, one of Italy’s best, brought to Canberra in 2011 by the National Gallery.

An annual festival is one thing. Donizetti’s art also translates to the TV screen which may be a big part of opera’s future. This is spectacularly confirmed, both for opera in general and Donizetti’s work in particular, by the streaming service of the Metropolitan Opera New York. It offers 15 videos of Donizetti including a stellar 1982 production of Lucia di Lammermoor with Joan Sutherland and tenor Alfredo Krauss, conducted by Bonynge.

It also offers HD videos of Donizetti’s three operas about the drama of the Tudor court, presented by the Met over the last 10 years: Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda and Roberto Devereux (the last about Elizabeth I and her thwarted love). They are lavishly produced and powered by vocal stars.

The American mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato, sings Mary Stuart at the Met. She says of the confrontation between her character and Elizabeth, there is nothing that competes with it in all of opera. Opera Australia confirmed this in a concert performance in March this year of Robert Devereux. Even with the cast singing at lecterns and no staging, the drama sizzled, propelled by Donizetti’s galloping rhythms.

Watching the first act of Anna Bolena on the Met site, I appreciated Donizetti’s skill in creating deeply ambiguous characters, exposing warring emotions and the dollops of self-loathing in Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour. His music dramas expose psychology as vividly as the words of Shakespeare or novels of Hilary Mantel. He paved the way for later masters, Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner, in their mature works, to deliver the final statements in the marriage of drama and music to which opera aspires.

The CEO of Opera Australia Fiona Allan says: “One of the reasons Donizetti remains of such influence today is that he creates characters so vivid and emotionally deep. They provide a vehicle for our most exciting singers to show off both their dazzling vocal techniques and their acting. Dame Joan Sutherland and Luciano Pavarotti gave us epic performances that live in our memories.”

The revival of bel canto opera in the 1950s and 60s owes a lot to Richard Bonynge. Bonynge retrieved a treasure trove of musical scores of Donizetti, Rossini and Bellini, and guided his wife to mobilise her stupendous voice for the challenge of bel canto rather than, say, the music of Wagner. It was with the role of Lucia at Covent Garden that Sutherland, the 33-year-old from the Sydney Con and the Sun Aria competition, became overnight one of the world’s prima donnas.

I recommend Sutherland in Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia at the Sydney Opera House in 1977, conducted by Bonynge and available on YouTube. As the curtains closed, David Malouf, the Australian novelist, apparently said to a companion, “Now that was bel canto!”

There was no other response to the soprano’s triumph in a ridiculously difficult final aria, and her dramatic collapse on the stage.

At Covent Garden in 1980 in the same role she received an exultant public response and critical endorsement that could only have confirmed her status, with Melba, as the most globally celebrated of any Australian artist in any field.

Richard Bonynge told me, “I love the big tragedies of Donizetti- Borgia, Maria Stuarda and Anna Bolena especially.”

In August, Australian bel canto soprano Jessica Pratt demonstrated her virtuosic singing in a performance of famous mad scenes, three from Donizetti.

Fiona Allan says: “There are good reasons every major opera company keeps Donizetti operas in their repertory. New generations of audiences fall in love with his characters, his storytelling and his musical fireworks.”

Donizetti gives us comedies as well.

Last November at the Vienna Staatsoper, (my wife) Helena and I were riveted by a precious moment in Donizetti’s 1832 The Elixir of Love, one of the most performed of all operas in the repertoire. The tenor playing the simple peasant Nemorino stood alone on the stage. He faced an audience of 2700 on five levels of the marbled opera house, all hanging on his delivery of the famous aria “Una furtiva lagrima” which means a furtive tear, the one, he thinks, he glimpsed in Adina’s eye, proving she loved him.

There are four productions of The Elixir on the Met site. It will be performed again this November in Vienna and Covent Garden.

In Don Pasquale Donizetti took the stock characters of the commedia dell’arte – the old miser, the cheeky soubrette, the cunning servant – and invested them as pulsing humans. Almost the last he would write, Don Pasquale is the culmination of his creativity.

Elixir and Don Pasquale are his two opera buffa masterpieces. The cunning, ticklish melodies on their own make you smile. Two masterpieces for which the wacky Chiara e Serafina of 1822 was a preparation.

On the streaming service Medici.tv you can find a production of Don Pasquale from the 2022 Glyndebourne Festival. Elegantly designed, it reveals a perfect alliance of comic theatre and the small, classical early 19th century orchestra.

Donizetti returned to Bergamo in 1847 racked with mental derangement due to syphilis, the emblematic disease of the century. His tomb is in Bergamo’s Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. Here, opera pilgrims may reflect on the hours of joyous music he created and that, between the death of Rossini and advent of Verdi, he was Europe’s greatest opera composer.

He saw out his last days, tragically, “broken, sad and incurably sick.”

The statue on his tomb is an angelic muse, head bowed as if shedding a furtive tear.

Bob Carr was the longest-serving premier of NSW and former foreign minister of Australia.